The Leper Spy (29 page)

Authors: Ben Montgomery

Joey appealed to Secretary of State John Foster Dulles. “I am writing to you because I am convinced that you are one of the most influential ⦠men in this country,” she wrote. “Please, Mr. Dulles, could you speak for me, and perhaps ask someone in power at Congress to do something about my billâevery year I am threatened with deportation and it has been a source of worry for me.”

With the help of the American Leprosy Missions Inc., Joey brought her story to a West Coast television show in late 1959, essentially outing herself. She appeared on Paul Coates's

Confidential File

with a doctor from India who specialized in Hansen's disease. Her employers at Levi Strauss & Co. knew about her past, but her coworkers were unaware. The program was powerful.

“Let me tell you this,” the wife of a former Carville patient wrote to the

Star,

“and you can tell everybody at the hospital, that this little woman, who suffered so much, did more in half an hour than any doctors or any other human being to understand and not fear people afflicted with this illness. She spoke so sincerely and so beautifully that millions of hearts ⦠that day, were filled with compassion and understanding and shame for their ignorance.”

Joey knew the risks. “If I lost my friends simply because they found out I had Hansen's disease, then they weren't my friends in the first place, which would make my life less complicated,” she told a reporter. “And yet, perhaps I would make new friends because of all that.”

She did make new friends. A Hollywood screenwriter named Virginia Kellogg Lloyd invited her to dinner at the swank Hotel Bel-Air, and they later went to a party at the home of writer Robert Carson.

Her employers also began to lobby on her behalf. The chairman of the executive committee even flew to Washington to press legislators to do the right thing. “She is an able and conscientious

worker,” wrote R. M. Koshland, personnel manager at Levi Strauss. “She is cooperative, loyal, and also popular with our other employees. I can vouch for her integrity, as well as character. I can think of no one who is more deserving of citizenship than Mrs. Lau.”

Morrison introduced bill after bill, H.R. 2412, H.R. 1278, H.R. 5092, H.R. 2960, H.R. 1737. More lawyers joined the fight. Years trickled by with no action, and Josefina V. Guerrero legally became Josefina Guerrero Lau, and when her relationship with Alec Lau ended, she changed her name again to Joey Leaumax, completely losing any bureaucratic connection to the woman who made headlines. She applied for an adjustment status, one final administrative possibility.

“On July 12, 1961, the decision was rendered,” her new lawyer, Norman Stiller, wrote to Morrison, “denying the application on the ground that Mrs. Leaumax is inadmissible to the United States for permanent residence in that the United States Public Health Service has certified that she is afflicted with Class âA' Leprosy. It would appear from this decision that we have now exhausted administrative remedies, although it is true that an appeal can be made to the Regional Commissioner, but inasmuch as this is a medical finding the chances of having this decision reversed is practically nil.”

Class “A” Leprosy. The same reason Morrison's bills failed.

Joey appealed anyway. The terse two-sentence response said the decision was final.

Morrison had no recourse but tried again, submitting H.R. 8751, a plea for relief for Mrs. Josefina V. Guerrero Leaumax.

“You may want to call it to the attention of the Immigration Service,” Morrison wrote to lawyer Stiller, “in the hope that as long as the Judiciary Committee doesn't act upon it during this session of Congress (which action without doubt would be unfavorable) deportation action might be withheld.”

When news broke about what seemed to be the government agency's final decision, phones started lighting up across Washington, DC. Joey's friends staged one last protest, calling every powerful

person they knew. Among Morrison's notes is a scrap of paper, a note to calm the callers. “Miss Towne in Immigration here at main office says, for our information: RE Mrs. G, just tell inquirers that as we understand, Mrs. Guerrero is in non-priority status, which means she is placed in the hardship priority. (that's good, no one will touch her),” the note says. “Miss Towne says this woman will never be deported on account of the tremendous publicity Immigration would be liable to.”

SUNSET

R

enato Ma. Guerrero fell dead on December 1, 1962, just before he was to deliver a lecture at the University of Santo Tomas. Stanley Stein published a memoir about his own life in 1963â

Alone No Longer: The Story of a Man Who Refused to Be One of the Living Dead

âand the press called it “a testimony to courage” and “an eloquent plea for understanding.” Gen. Douglas MacArthur died on April 5, 1964, at Walter Reed Army Medical Center, and he was buried in a GI casket and ribbonless blouse, conspicuous in their simplicity.

Two months later, in San Francisco, California, Joey Leaumax got a letter from the INS and hurried to share the news with Congressman Morrison.

I am sure you will be happy to know that I have received my permanent residence card. I was told that after three years, I may apply for American citizenship. At last, your hard work and concern have been rewarded. Will you also convey to your secretary the good news, as I know whenever you were away she wrote the letters and she wrote me cheerful letters of encouragement.

I want you to know that I am deeply grateful of your efforts in my behalf, and for your fight to keep me in

America. Has it ever occurred to you that in all this time we have never met, and yet I feel as if I have known you all my life. I think you are a truly kind and good man because I am a total stranger to you but you have continuously championed my desire to become an American citizen. It was indeed a hard and arduous climb uphill, but we have reached the top which can only be surpassed

when at long last I am allowed to become an American citizen. That will be a great day for me. Three years will soon pass and I shall be prepared for that day.

Once again, thank you for your many kindnesses in the past, for your untiring efforts to put through the bill, for everything that has made possible my stay in America. I have other letters to write to people to whom I owe gratitude, so for today, goodbye, and as we say in Filipino,

marami pong salamat.

I hope to come to Washington one day soon, and when I do, I shall make it a point to come and see you and greet you and it will be a memorable visit for I shall be meeting you for the first time. Kindest, personal regards to you and your secretary.

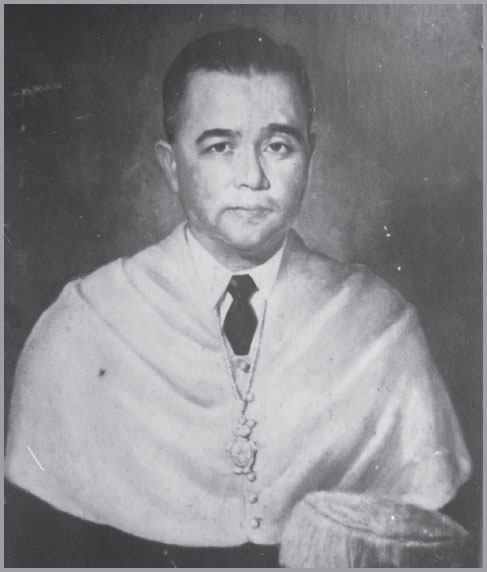

A portrait of Renato Ma. Guerrero.

Courtesy of Cynthia Guerrero

Then, a surprise. Joey answered the door one day, and there stood her daughter, Cynthia, holding an infant. Her little girl was a woman now. She wasn't tall like her mother expected. They stood about the same height, and the daughter bore a striking resemblance to the mother.

Cynthia didn't know what to expect. She had only the vaguest memories of her mother, of the visits to Tala Leprosarium and the room full of books, but she had always wondered what it would be like to see her again. The family on her father's side did not understand this desire. “Why do you want to meet her?” they asked. “Why would you do that?”

They blamed Joey for leaving the family, for divorcing Renato. Her father cried to the end of his life, Cynthia said, holding out hope for a cure and that his wife would someday return. He'd tried to move on, and he'd had girlfriends but never another deep relationship. He buried himself in his work. Her grandmother, Renato's mother, would speak ill of Joey in Spanish, critical of the divorce. But Cynthia always wondered.

Cynthia took her burden to a priest, who explained that when a person contracts leprosy, when they're forced to give up the things

and people they love, when they're sent to the edge of society, they change. Psychologically, emotionally. They are rejected, so they, too, must reject.

“You feel like a social outcast,” the priest said. “You feel left out, you feel like you've been ostracized. That is what happened to her. She just wanted to turn her back.”

Cynthia's classmates, some of whom had moved to California, had offered to help her find her mother. When her father died, she was trying to settle the estate and had money for her mother from the sale of a lot in Quezon City. She flew to California to deliver the monetary gift.

Joey was thrilled to see them both and doted on the baby, her first grandchild. But, according to Cynthia years later, the baby was ill with diarrhea. “She couldn't keep anything down. We stayed there about a week,” she said. “She got so sick, so sick. When you have a baby like that, you get scared.” She thought maybe it was the weather. She wasn't sure if she should take her ill child to an American hospital. Her husband suggested she come home. She already had a return ticket. She told her friend to tell her mother good-bye, for she could not bring herself to say it again. And then she left.

“It's not that I didn't love her,” Cynthia would say years later in her little home on the outskirts of Manila. “It's just that I didn't know her.”

She still wonders how a mother could leave her child. There are no signs of Josefina Guerrero in Cynthia's home, no photographs or letters or Christmas cards. She has one photograph of her father, and she is proud that he is still remembered with an annual lecture at the University of Santo Tomas. Her feelings about her mother are more complicated.

“Maybe her sickness affected the mind,” Cynthia said.

The nuns used to remind her not to hate. She said she does not harbor any hard feelings, but the hurt is always there, even in her old age.

“We're all bidding the world good-bye, I suppose.”

DISAPPEAR

S

he was leaving a diminishing trace that she had walked the earth, that she had done great things and was recognized for them. She was tiring of being recognized, because with the recognition sometimes came judgment. She wanted to cast off her old life and try anew.

The final public attention she'd receive on a scale larger than a church bulletin came in late 1967, in the pages of the

San Francisco Chronicle

in a story penned by William Cooney. Joey Guerrero Leaumax, diminutive Filipino war heroine and former Carville patient, had finally gained US citizenship. It had taken a grateful country twenty years to tell the leper spy, yes, you may live here.

She spoke of giving food and medicine and cigarettes to the men on the Bataan Death March and taking the same supplies to prisoners at Los Baños and Santo Tomas. The story recalled her intrepid journey to deliver the minefield map to the Thirty-Seventh Infantry Division, but she was hesitant to talk about it.

“I really don't like to talk about it,” she said. “I have almost forgotten.”

When she finally told the story, it was not embellished by ornament. She spoke plainly, just the facts. “They gave me the map and told me to deliver it to Malolos,” she said. “I walked, went by banca, and walked. There were snipers everywhere. I hid and walked. And

when I got there, the Americans had moved to Calumpit another 25 miles. So I took it there.”

There were moments when she seemed to harbor regret. She recalled the Japanese officers she befriended in order to get what she needed for the guerrillas.

“We had to get information from them,” she said. “Some of them were very nice. They would show me pictures of their wives and children ⦠and there I was sending them to their deaths.”

After the story ran, she wrote to the

Star

to say she was now trying to graduate from San Francisco State College, majoring in English with a minor in Spanish. She had worked for several years as a secretary and librarian but decided she wanted to go back to school. She said she wanted to be an elementary school teacher and was working on the campus for the Experienced Teacher Fellowship Program and was hoping to study abroad in Spain. She asked the

Star

to publish her thanks to Robert Kleinpeter of Baton Rouge and Normal Stiller in San Francisco and Congressman James Morrison and all her friends at Carville.

It was the last time she would make headlines. The little woman who kept company with generals and cardinals would soon disappear from the pages of the newspapers and from the minds of most Americans, just like the disease that made her who she was. She would pawn her Medal of Freedom with Silver Palm. Her story would be all but lost, just as she wanted it.

I AM STILL ALIVE

I

n August 1970, Dr. Leo Eloesser began writing letters to his contacts far and wide. He was eighty-nine, living in Mexico, and trying to tie up loose ends. He had not heard from or about Josefina Guerrero since 1948, when he had written letters on her behalf, trying to cut tape to get her to America.