The Leper Spy

Authors: Ben Montgomery

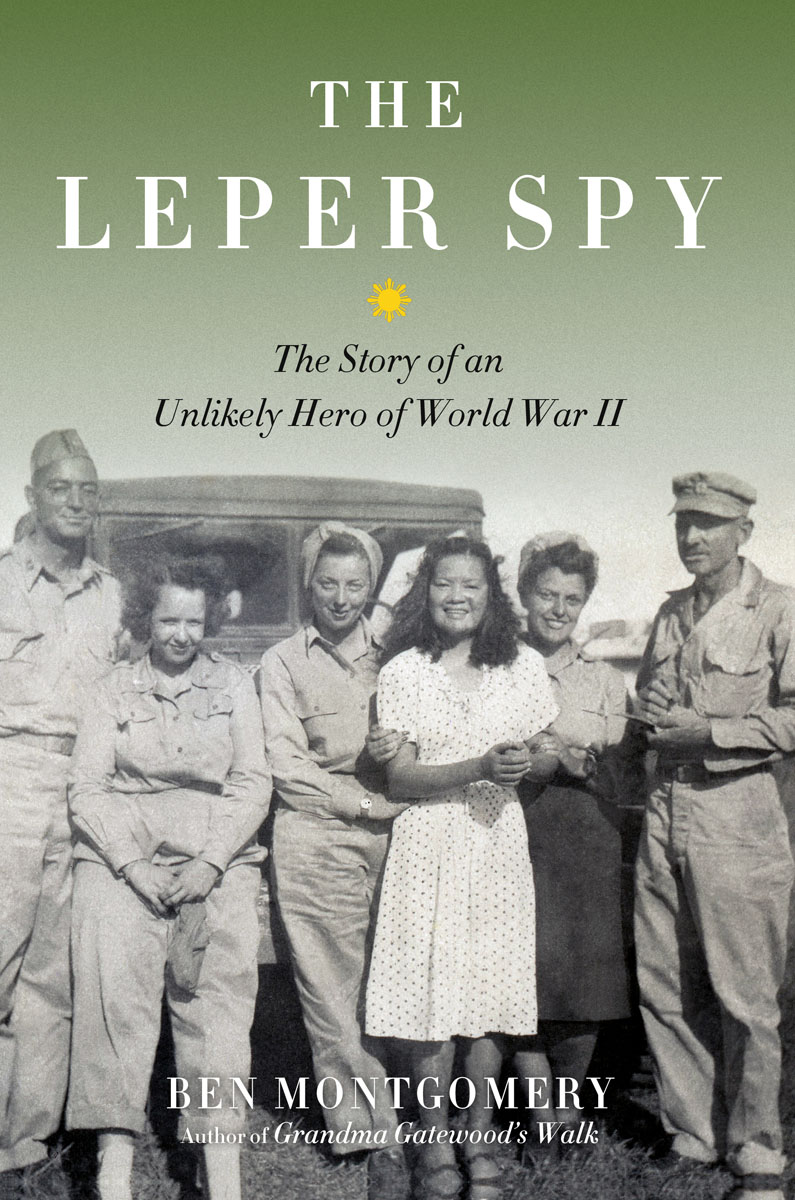

THE LEPER SPY

T

he GIs called her Joey. Hundreds owed their lives to the tiny Filipina woman who was one of the top spies for the Allies during World War II, stashing explosives, tracking Japanese troop movements, and smuggling maps of fortifications across enemy lines for Gen. Douglas MacArthur. As the Battle of Manila raged, young Josefina Guerrero walked through gunfire to bandage wounds and close the eyes of the dead. Her valor earned her the Medal of Freedom, but the thing that made her an effective spy was a disease that was destroying her.

Guerrero suffered from leprosy, which so horrified the Japanese they refused to search her. After the war, army chaplains found her in a nightmarish leper colony and campaigned for the US government to do something it had never done: welcome a foreigner with leprosy. The fight brought her celebrity, which she used on radio and television to speak for other sufferers. However, the notoriety haunted her after the disease was arrested, and she had to find a way to disappear.

Copyright © 2017 by Ben Montgomery

All rights reserved

Published by Chicago Review Press Incorporated

814 North Franklin Street

Chicago, Illinois 60610

ISBN 978-1-61373-430-8

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Montgomery, Ben, author.

Title: The leper spy : the story of an unlikely hero of World War II / Ben Montgomery.

Description: Chicago : CRP, [2016] | Includes index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2016002542| ISBN 9781613734308 (cloth : alk. paper) | ISBN 9781613734339 (epub) | ISBN 9781613734322 (kindle)

Subjects: LCSH: PhilippinesâHistoryâJapanese occupation, 1942â1945âBiography. | World War, 1939-1945âUnderground movementsâPhilippines. | Guerrero, Josefina.

Classification: LCC D802.P5 M66 2016 | DDC 940.54/8673092âdc23 LC record available at

http://lccn.loc.gov/2016002542

Interior design: Jonathan Hahn

Map design: Chris Erichsen

Printed in the United States of America

5 4 3 2 1

For my mother, Donna

One life is all we have, and we live it as we believe in living it, and then it's gone. But to surrender what you are, and live without beliefâthat's more terrible than dyingâmore terrible than dying young.âJ

OAN OF

A

RC

, in

Joan of Lorraine

by Maxwell Anderson

Lord, if thou wilt, thou canst make me clean.

âG

OSPEL OF

M

ATTHEW

1Â Â Â Everything Is in Readiness

Washington, DC

In the last years, when she was living quiet and alone in the bustling capital of a country that had forgotten who she was and what she had done, she never spoke of the war. She kept the stories inside her head. No more bullets bit the dirt at her feet, and the flashbulbs had long since faded. Her few friends around town had no idea that she had once walked unflinching through cross fire half a world away, helping the fallen to their feet and closing the eyelids of the dead. They never knew the diminutive woman did something so daring that a US Army major general pinned a medal to her breast and said she had “more courage than that of a soldier on the field of battle” and that a Jesuit priest called her “one of the greatest heroes of the war.” They would ask where she was from, and she'd tell them she was born inside an airplane high over the Pacific, or in San Francisco. Nothing more. No one even knew her real name.

Her posture was perfect, but she was tiny and easy to miss on the broad boulevards of Washington, DC, the lines of taillights stretching forever past her, the sidewalks a two-way stream of people trying to get somewhere else. She'd dress in a black skirt and plain white blouse and pull on a long coat and slip out of her apartment on New Hampshire Avenue and walk a few blocks in the fading sun to the grand John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts, on the

east bank of the Potomac, where she was Joey Leaumax, usher, volunteer. She'd show patrons to their seats with an anonymous smile, then disappear into the shadows to let the music wash over her.

That's why she was here, the music. She was a plain person, but she liked to say that the plain is always attracted to the beautiful. She never played an instrument, but she was raised on classical, heard it in her sleep, and it conjured images of her childhood, happy and peaceful, before the war, before her affliction, before she had to disappear in order to live. Her secret ambition had always been to visit all the places where she could embrace music: Carnegie Hall, the Metropolitan Opera House, the Hollywood Bowl. She fed her soul on concertos for piano and violin. She loved Chopin, Beethoven, Debussy, Saint-Saëns, Tchaikovsky. Humperdinck's

Hänsel and Gretel.

Mendelssohn's

A Midsummer Night's Dream.

Ravel's

Daphnis et Chloé.

Her favorite was Brahmsâso soothing, like a journey into a land of magic dreams. She was especially fond of his Symphony no. 1 in C Minor. Of the four movements, she liked the second best of all. She felt like it was pregnant with unspoken yearnings, secret desires, until finally it broke into the third, the allegretto, so alive and intense until it reached the finale and the air exploded with music and excitement, like the sudden appearance of a white-hot sun after a rainstorm.

To find the music, she had to travel halfway around the world, then battle the great bureaucracy of the US government, then ultimately disappear into the roving citizenry. But finally. She would close her eyes and lose herself in the sound and at once see her mother and her daughter, whom she had left behind. Her brown-eyed little girl, a stranger now.

Those times were past and sealed in a box in her mind, and she would let them out to run and play up the crescendo.

She was Joey now. She had a simple apartment overflowing with books and a compact disc player and recent memories of a job as a clerk at the Gold and Silver Institutes, where she typed letters,

her eyes straining behind thick glasses. She was always giving her things away, foisting books upon her visitors, who always felt bad because she had so little to give. She walked to Mass every day at St. Stephen Martyr and took the body and blood of Christ into her mouth, a sacred and consistent act, then walked home to be alone.

When her heart finally gave out a little after five o'clock on the morning of June 18, 1996, there was no grieving or gnashing of teeth. She left behind modest home furnishings; some costume jewelry; 850 books; two bags of used foreign stamps; foreign banknotes and traveler's checks; some vinyl records; many autographed ballet, opera, and theater posters; photos and Playbills; and a simple handwritten will and testament, leaving the little money she had after her debts were settledâabout $5,000âto a handful of friends. Those trying to settle her affairs also found a mystery.

They found address books that, quite curiously, contained only the names of friends she had made starting in the 1970s, none from before. In calling these friends to alert them of Joey's death, no one seemed to know anything about her parents or when or where she was born. Among her possessions, there were no photographs taken prior to the late 1960s and no personal documents with an earlier date. Her passport said her place of birth was Manila, in the Philippine Islands, but none of her friends had ever heard that. She listed her year of birth as 1917, 1927, and 1937 on various documents. Her studio apartment was packed with years of catalogs, newspaper clippings, and correspondence, but there was nothing among her possessions to suggest she had ever been married or had a family. The friends assumed she was born in 1927 and had never married. Her death certificate and obituary would reflect the errors.

At her funeral a man read “Desiderata,” and they buried her ashes in a box in a marble wall inside a chapel at Mount Olivet Cemetery, on the east side of the city. The funeral was well attended, and her obituary ran in the

Washington Post

beneath one for a money manager and above one for a chef, on June 28, 1996:

JOEY GUERRERO LEAUMAX

K

ENNEDY

C

ENTER

U

SHER

Joey Guerrero Leaumax, 68, a retired secretary who had worked as an usher at the Kennedy Center for the last 17 years, died of cardiopulmonary arrest June 18 at George Washington University Medical Center.

Ms. Leaumax, who had lived in Washington since 1977, was a secretary in the publications department of the Gold and Silver Institutes in Washington from 1977 until her retirement in 1990.

She was born in Manila and graduated from San Francisco State University. She received a master's degree in Spanish literature from Middlebury College, then spent four years as a Peace Corps volunteer, teaching English, music, and drawing to children and adults in Niger, Colombia, and El Salvador.

She was a member of St. Stephen-Martyr Catholic Church in Washington.

She leaves no immediate survivors.

A week after the obituary ran, a man called Joey's friend who had made the funeral arrangements. The man said he had known Joey Leaumax by a different name fifty years ago, in southern Louisiana. He told an astonishing story of a previous chapter of her life, unknown to her friends for the past thirty years.