The Last Supper (16 page)

Authors: Rachel Cusk

The Museo Archeologico Nazionale is nearby: it stands amidst a great swirl of roads and ruined buildings and whole devastated tenements showing their foundations like toothless gums. Some of the ruins have classical shapes. From certain angles the scene looks like photographs of Berlin after the

Blitzkrieg

, and from others like the mystical background of a Leonardo Madonna. The museum itself is a grand sixteenth-century edifice, as well kept as any Florentine art gallery, but a significant difference separates it from the usual haunts of the northern art lover: it is virtually empty of people. It is ten o’clock in the morning and as far as I can see we are the only ones here. The lady who takes our tickets in the beautiful modern glass entrance hall looks as delighted to see us as if it had been days since her last visitor; the people in the lavishly furbished cloakrooms want to know everything about our travels and future plans. The curator at the turnstile knows the children’s names before they are fully out of their mouths: she strokes their red hair, almost sobbing with pleasure, and admires the drawings in their sketchbooks. Where are the people with suitcases and long lenses, the people in baseball caps and khaki shorts, the scholars and the misfits, the bored teenagers, the tourists fat and thin, the freaks, the fashionable people, the crowds? Where is the cultural ennui? What can the explanation be? Is it possible that they’ve been scared away by stories of pickpockets on scooters? Do they have so much cash that their underwear can’t conceal it? Are they so wedded to their jewellery that they would rather stay at home than leave it behind? Is their aestheticism so shallow, in spite of the hours they spend queuing in its service, that they would rather not come? I find it a little eerie at first, their absence from the sculpture court, from the rooms of the Farnese collection. The

Greco-Roman marbles from Pompeii and Herculaneum in the atrium seem to come forth in their strange reality without them there, chewing gum and looking at everything spastically through the lenses of their mobile phones, like earth tourists from outer space. How curious it is, to be here alone! Usually great artworks are so outnumbered by the mob that they seem fragile, almost victimised. But here in the silent, light-filled museum the correctness and cruelty and might of the ancient world is unsheathed.

We wander in the sculpture court, where giant marble limbs and heads and hands lie fallen to the ground and there is a white carved foot the size of a car. Put together the pieces would make a figure fifty feet high. In 1980 the museum and its collection was badly damaged by the same earthquake that presumably gave its environs their appearance of

Blitzkrieg

, though it was not then that the giant fell. Apparently his parts were found buried in the garden of the Villa Farnese. The life of an object is so long, its destruction so heterogeneous. It does not die a single death, like us. It lives on as a hand, a head, a foot. It is buried and reborn. What does it signify, this enormous foot? That man has always been the slave of ambition? It was the restoration work after the earthquake that gave the museum its lavish modern appearance. The earth shook it like a box of sweets, this building full of treasures that had already been drowned in the fire and mud of Vesuvius and resurrected. How murderously it pursued them; and yet the human faculty of love, of patience, that can look on the ruined spectacle of glass and marble and mosaic tiles, all broken and scattered and muddled up, and set about piecing them together again is as strong in its way as violence. This is one reason why the art lover enjoys looking at art. Each object represents another triumph for love, for survival, for care. Each object can be placed on the scales, against man’s violence and destructiveness. Which way the scale will tip at the end of it all, nobody knows.

In the atrium there are Aphrodite, Artemis, Athena. I would like to hear their life stories: I would like to know how the

world that created them became the world in which they still stand. Their garments fall to their feet in milk-white marble folds; their tapered white fingertips caress the empty air. But their eyes are so blind, so blank: truly, there is death in their unseeing elliptical eyes. It is the death not of themselves but of everything they have looked upon. Their eyes are like mirrors that reflect the void of death. I think of Cimabue, of Giotto, of Duccio’s

Maestà

that we saw one day in Siena; of their gilded Madonnas stirring in their painted rigidity, struggling to be born and become mortal. They did not wish to look indifferently on the void of death. They strove to express the authenticity of emotion. Yet they are so unlifelike, compared with these pitiless maidens whose painted eyes time wore effortlessly away, to uncover the annihilating gaze beneath.

Upstairs there are several rooms devoted to the domestic life of Pompeii: everything has been reconstructed, the triclinium and the peristyle, the kitchen with its pots and pans, the dining table with its battered plates and spoons and ashen loaf of bread, as though its owners were about to sit down and eat; as though it were not a place but a moment in time that was captured and sealed in its carapace of volcanic dust. I am struck by the importance of innocence in our view of tragedy. For an incident to satisfy our tragic sense there must have been a predominance of hope over knowledge. There is innocence at the supper table: the loaf of bread, humble though it is, is quintessentially tragic. There are indentations in the risen crust, where the person who made it neatly scored the surface with a knife. The children look at the two-thousand-year-old loaf of bread. I do not think they are marvelling at its preservation alone. It is the fact that the bread survived and the people did not that interests them. They would like to taste it. It is almost maddening to them, this triumph of the familiar object. Will the bread never be eaten? Will it just get away with it, for another two thousand years? I myself often make bread, and score the surface with a knife. It is not for this feat that I would like to be remembered, but there is a steadiness to the act that

I have noticed many times. There is a feeling of centrality that is directly opposed to the marginal position of the writer of books. Most of all there is a feeling of something lasting, though the bread itself will be eaten soon enough. No, it is not the bread that is the durable object: it is myself, in the act of making it. I am no longer the artist – I am the subject. I am the person in the painting, not the painter. It is strange, that the feeling of immortality should disclose itself in this way, in the prosaic. Nietzsche said that art is what enables us to bear reality. Perhaps what he meant is that it distils the eternal from the everyday and puts it beyond the reach of tragedy.

In the Sale del Tempio d’Iside there are beautiful frescoes, of fruit and flowers and doves preening in a water-bath, of men and women, of horses and battles, of gods and satyrs and maenads and scenes from mythology. There are paintings and poems, jewellery and glass vases, erotic cartoons and a beautiful egg poacher, whose beaten metal spheres seem to revolve like the planets of some far-off solar system. There is a whole museum within a museum, the contents of the Villa dei Papiri where Julius Caesar’s father-in-law housed his art collection. It is disconcertingly alive, this vanished world of Pompeii. The silent museum seems filled with noise, with faces and glancing eyes and conversation, clattering pots and barking dogs and birdsong. It is as though the volcano did not extinguish the day but took its cast exactly, its sound and smell and atmosphere, its structure, like the skeleton of a fern fossilised in a lump of rock. We go out into the shady courtyard, where a young man gives us glasses of lemon

granita

, diligently, as though he had waited all morning for us to be ready. We sit under a tree. There are one or two other people around, reading books in the shade. Nobody knows we are here. We sit quietly, letting the ice melt a little each time, before we take a sip.

*

Pompeii is reached from Naples by the Circumvesuviana, a small, grey, graffiti-covered train that looks like it was born in

a subway of the Bronx. It charges around the Bay of Naples, through the sprawling conurbations that lie to the south and on to the resorts of the Sorrentine Peninsula, tunnelling furiously through poverty and grandeur alike, as though it didn’t care for the difference between them. At the stations it flings open its doors, fuming with impatience: the passengers hurl themselves out and the train springs away, rattling helter-skelter past high-rise tenements and Palladian villas, past fragrant glimpses of orange groves, ducking and diving between the volcano and the sea and never pausing too long in the purview of either.

It is very hot, so hot that the plastic bucket seats of the Circumvesuviana are painful to the flesh. If the train stops for more than a few seconds, a feeling of panic sweeps up and down the crowded carriages. At Pompeii we get out and walk along the dusty road in the sun, past the queue of air-conditioned coaches that are disgorging tourists from their sides. There is a little cafe next to the road, and we sheer off to sit beneath its shady vine and drink Fanta. From our dark corner we scrutinise the crowds. After two and a half months in Italy, we have the demeanour of outlaws when faced with our own kind. And these are the worst, these herds who drive around in coaches, looking numbly down on the world. They are not art lovers. They aren’t even really tourists: they are voyeurs.

There is a throng of people at the entrance, but it doesn’t take long to get our tickets. I have begun to understand that in Italy a crowd does not necessarily represent an obstacle to desire. Much of the time, people amass for reasons of their own. They queue because they want to, or because their relationship with the thing they are queuing for is insufficiently direct. Often the people standing in a queue will all be queuing for entirely different things. Then there are the people who can never believe that they are in the

right

queue, who continually ask their neighbours what the queue is for and send waves of unrest up and down its length. And there are those who seem to queue solely for the feeling of security it gives them, as

though it is only in the queue that they are truly safe from another fresco, another Madonna, another Donatello head, about which they might be compelled to give an opinion, or fail to feel something they were told they should. The Italians respond to this dissociative behaviour with the utmost cordiality. Nothing summons their compassion more readily than a devitalised tourist, and their sympathy grows in direct proportion to its object’s lack of charm. It is as though the thing they pity most in all the world is ugliness.

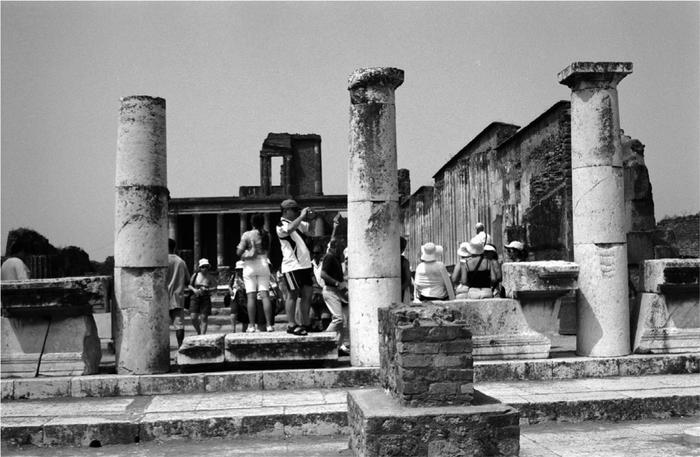

We pass through the gates and out into the cauldron of afternoon. The integuments of the ancient town, diagrammatic, skeletal, pure as bone, rise and extend in terraces all around: everywhere the force of extension drives towards its own vanishing point, for the town is flat, radial, star-like, with few upright walls to arrest the driving force of the straight line towards the horizon. The effect is ghostly: the volcano, so pyramidal in mass and shape, so grossly upright, lowers over the prostrated, map-like town. It is corpulent where the town is abstracted. It has devoured it, and left the bones. Yet there is something religious about the driving symmetry of the lines, the mathematical stepping and extending of the ruined terraces into space. There is a system, an order, a plan. The volcano is a mere beast. The plan, the mathematical essence of civilisation, defies it.

The tourists are delighted with their new home: they stroll and chatter in the deep ridged streets, they pass in and out of doorways, they minuet at corners and crossroads, now deferential, now proprietorial, as though they had donned its social hierarchy like a fancy-dress toga. The forum is filled with its rightful bustle; people come and go at the bakery and the baths. It is a shame they can’t live here, they seem to like it so. Sometimes, in a shady corner, a glass case is to be found with a rough grey shape lying inside: these are the casts the volcanic ash cruelly made of its victims, to immortalise their helplessness. They are crude and barely human; they are like primitive clay figures. Yet their blurred, blank quality is disturbing. It is

somehow more embryonic than deathly. We stand around the glass cases sadly, as though their contents only needed our compassion to humanise them again. The inexactitude of the figures: how mysterious and elusive it is, when their pots and pans and egg poachers have come down to us unharmed. There is an atmosphere of guilt around them. The cases are shabby, and filled with grit. Could they not be resting on something more comfortable? They seem so unloved, lying there in their strangely unfinished, unborn state.

The day grows hotter; the volcano is cloaked in haze; in the distance the blue sea lies passive, recessed, a strange fluorescence pulsing on its surface. The crowds seem to grow more and more excited. They seem a little crazed. They seem over-exposed. They rush hither and thither like children playing hide and seek. They barge and tread on one another’s feet. They shove and yell in the amphitheatre, beneath the smiting sun. There is a group of German students, handsome and extravagantly dressed, who are following their professor around the ruins. They are tall and flamboyant and unrealseeming, like actors on a film set, like people in

The Great

Gatsby

. Their professor has a messianic appearance, in his

white flannel suit. I notice them, for they ask to be noticed. Amidst the heat and the ruins they have the carved, mocking quality of gods. Later, in the Villa dei Misteri, we see them again. The professor is chanting something in German, a strange, sonorous, interminable recitative that echoes all through the sepulchral rooms. Every now and again the students chant back to him in chorus. We cannot escape it, this mad Wagnerian oratory: the sound is sinister, almost frightening, as though a new cult were being hatched from the blood-soaked soil. We pass through room after room, taunted by the unbodied voices. Finally we come upon them, standing in the blood-red triclinium before the fresco of the Mysteries. The fresco shows a young girl being initiated into the cult of Dionysus. I might have found it beautiful had I been alone, for the girl’s mother rests her hand on her daughter’s shoulder and curls her fingers unconsciously around the tresses of her hair. The mystery and brutality of the pre-Christian world might have remained theoretical; the subject might have escaped me, as it generally does escape the art lover, in the face of the belief in art as an ultimate good.