Ice Drift (9780547540610)

Read Ice Drift (9780547540610) Online

Authors: Theodore Taylor

THE HAYES ARCTIC EXPEDITION, 1860-61:

Copyright © 2005 by Theodore Taylor

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or

transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical,

including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval

system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

Requests for permission to make copies of any part of the work should

be mailed to the following address: Permissions Department,

Harcourt, Inc., 6277 Sea Harbor Drive, Orlando, Florida 32887-6777.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Taylor, Theodore, 1921â

Ice drift/Theodore Taylor.

p. cm.

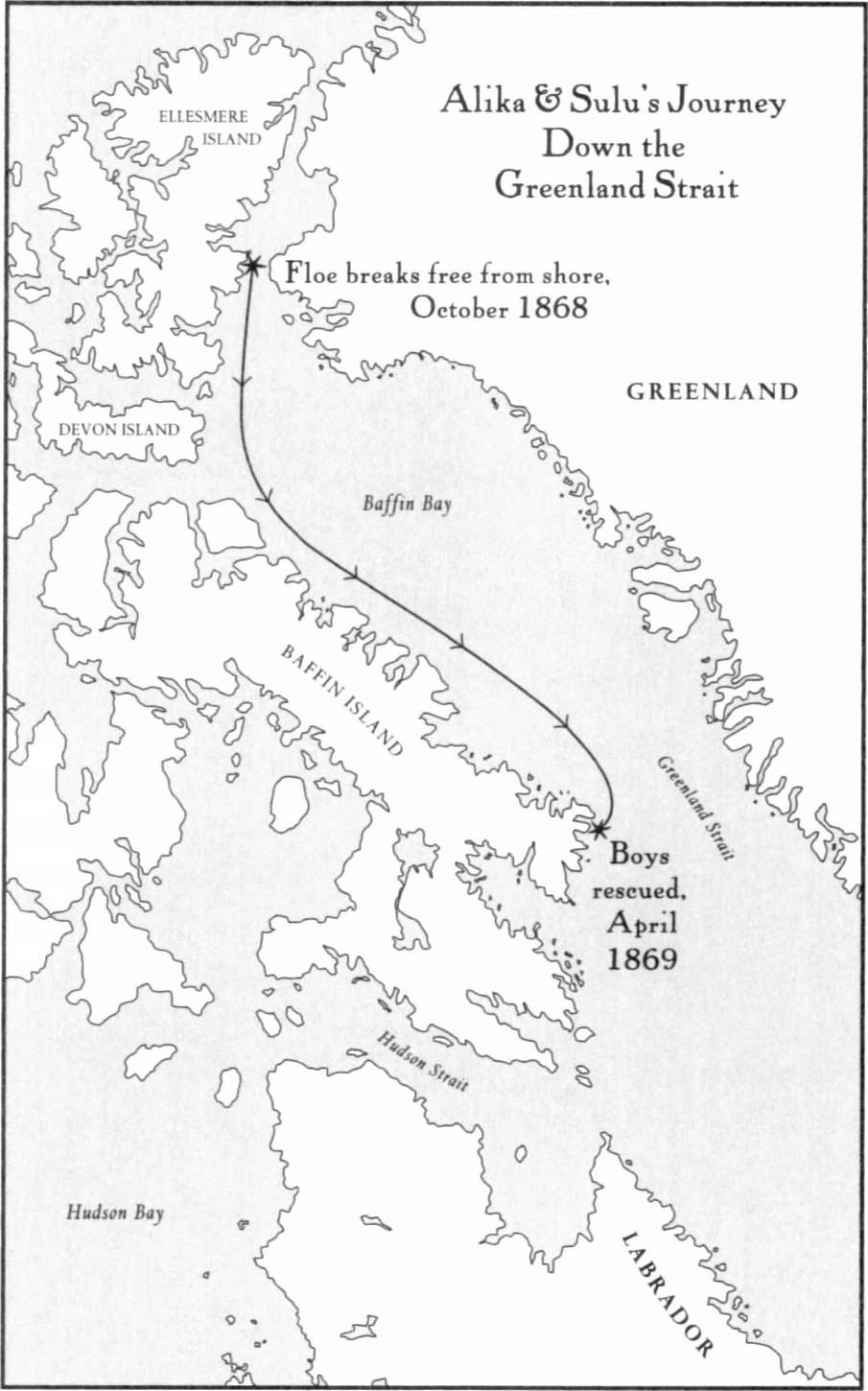

Summary: Two Inuit brothers must fend for themselves while stranded

on an ice floe that is adrift in the Greenland Strait.

1. InuitâJuvenile fiction. [1. InuitâFiction.

2. EskimosâFiction. 3. BrothersâFiction.

4. IcebergsâFiction. 5. Arctic OceanâFiction.] I. Title.

PZ7.T1286Ic 2005

[Fic]âdc22 2003027783

ISBN 0-15-205081-7

Map created by Tracy Hargis

Text set in Spectrum

Designed by Lydia D'moch

First edition

A C E G H F D B

Printed in the United States of America

For editor Allyn Johnston,

who piloted this floe of words with great skill

âT. L. T.

T

HE

A

RCTIC

C

IRCLE

The Arctic Circle, as laid down on maps, is a geographic

line of latitude drawn around the earth, parallel with

the equator and 23 degrees 30 minutes from the

North Pole. Within this circle lies the Arctic Ocean;

nearly all of Greenland; Spitsbergen, Nova Zemlya,

and other islands; northerly portions of Norway,

Sweden, Finland, Russia, Siberia, and upper Alaska

and Canada, including the new territory of Nunavut,

established in April 1999, with a population

eighty-five percent native Inuit. At the Nortk Pole,

the sun rises and sets once a year; the moon, once a month.

T

HE

H

AYES

A

RCTIC

E

XPEDITION

, 1860â61:

One incredible ice floe covered twenty-four square

miles. It rose twenty feet above the sea and reached

an estimated depth of 160 feet. The estimated

weight was six billion tons, a floating glacier,

expanding year by year, as the ancient ice, hundreds

of years old, remained frozen, fresh snow

accumulating and congealing into new ice above.

Alika, hand on his harpoon, his

unaaq,

ready for an instant kill, had been at the seal hole, the

aglus,

for three hours. His younger brother, Sulu, who had begged to join him on the hunt, napped beside him on the sledge. They were on the west edge of a large, thick ice floe attached to land in the Greenland Strait, waiting for a shiny seal head to appear. The floe was old. Perhaps it had broken off from North Greenland and had drifted across the narrow strait, refreezing against the remote Ellesmere Island bank.

The time was mid-October 1868, on the eve of the long winter darkness. The shallow noon light was already fading. Snow had fallen a week earlier and would stay until almost June. The caribou were mating, char were spawning, and the sea ice was forming. All over the Arctic, inhabitants, both human and animal, were preparing for the frozen siege.

Jamka, the lead sledge dog, had sniffed out the small hole where he expected a ringed seal would soon surface to breathe, and Alika had prepared for the day's hunt by building a windbreak of snow blocks and a snow-block seat next to the

aglus

that he covered with a square of polar bear hide to keep his bottom warm. An indicator rod of caribou bone was in the hole. When a seal came up, it might touch the thin rod, wiggling it and alerting him.

Many of Alika's elders often waited a day or two for just a single strike at the wily ringed seal or the bearded seal, the only two to spend the entire year above the Arctic Circle. But Alika didn't have the patience of his elders, and a worried glance at the snow-laden sky told him they should soon start for their village of Nunatak, which was seven miles south. A northwest gale was approaching. Alika could feel it coming, with its thick wind-driven snow. Winter weather was usually predictable eight hundred miles southwest of the North Pole. The stars had twinkled brightly the night before, often a sign of bad weather.

Descendants of the Thule people who had first settled in the north a thousand years before, fourteen-year-old Alika and his brother, ten-year-old Sulu, were Inuit, meaning "mankind," and their diet was mostly from the sea, mostly cooked.

Alika said to Jamka, "You promised me a seal a long time ago."

The Greenland husky, dark eyes always seeming to have an intelligent expression, stared back as if to say, "But I didn't tell you when."

Alika sighed.

Jamka squatted near Alika. At 110 pounds, he was a huge dog, with black-and-brown fur six inches thick. His undercoat was naturally oily to prevent moisture from reaching his skin. His bushy tail curled over his back. His ears were small, like those of most other Arctic animals, offering less area to absorb the cold of forty-five degrees below zero. He had a broad chest and big bones. There was wolf blood in him. In the Inuit tradition, the village children trained their dogs for sledge work. Alika had trained Jamka.

When Alika was seven years old, he and Jamka had bonded in an emergency, and they had been almost inseparable ever since. One September day, when the ice was still thin on a lake two miles from Nunatak, Alika was fishing for char when the crust broke. Into the water he went. Jamka pulled him out by the parka hood and dragged him home. Alika well remembered looking up at Jamka's wet belly as he slid on his back along the snow. He was convinced that Jamka thought like a human, and he trusted the dog with his life.

He looked over at Jamka and said, "I hope your nose isn't drying up." The adult hunters trained the dogs to sniff the seal breathers. Papa Kussu had done that.

Jamka continued to stare at the hole.

Ringed seals usually surfaced to breathe in what the white man judged as every seven minutes, but it was possible for them to stay down as long as twenty.

There were hundreds of the cylinder-like holes dug from beneath the ice. Three-hour waits were nothing, because the hunter could never tell which holes were being used. Only dogs like Jamka had that talent, and even they were often wrong.

Alika rose and called to the other dogs that were half buried in the snow. It was past time to go home.

Jamka stood up, also looking at the quickly darkening, threatening sky. Very experienced, Jamka seemed to sense danger in guiding the team, as if he knew exactly where hidden crevasses were; where the thin ice was. He'd fought polar bears and been wounded by them. He was the best lead dog Kussu had ever owned.

Then suddenly, unexpectedly, the floe shook and a loud crack shattered the stillness. Alika watched in horror as the dark expanse of water between the ice floe and the shore began to widen.

Three feet! Five feet! Seven feet!

Alika's body stiffened with fear and helplessness. The same thing had happened to several villagers without kayaks to reach shore. Their floe had split off, and they were never seen again.

Alika didn't know how to swim, and even if his feet

were

to find bottom and he could wade across carrying Sulu, water would seep into his polar bear pants and sealskin boots and underpants. Even if they could reach land, they'd surely freeze onshore, turn into human icicles. He needed time to cut snow blocks, build a small house, and start a seal-oil fire to dry their clothes. Going into the water would be a fatal mistake. The cold would kill them.

As he watched the shoreline fall away, Alika guessed that an iceberg aimlessly sailing slowly south down the strait, a ghostly and deadly mountain of ice, had rammed the floe, tearing it away from the permafrost shore, the always frozen earth. Now they were trapped in the gloom on a ship of ice, surrounded by hundreds of smaller ice cakes. The distance from shore would surely widen. Maybe they'd lose sight of the white-encrusted land completely. Total afternoon darkness was also near. They might not even see the village, where they lived with Papa Kussu and Mama Maja, as they slowly passed it. Unless they were very close, shouting would do no good in the wind and night.

Sulu had awakened, his small face a ball of terror. Alika said, "Don't worry, Little One, the wind will blow us back to shore." But he knew that chance was indeed slim. The prevailing wind this day was from the west, opposite of what they needed to reach shore again. He spoke in Inuktitut, the native language.

Thinking mostly of the Little One, Papa's name for Sulu, Alika shook the fear out of his head and tight stomach. One member of their village, old Miak, had survived being trapped on a big drifting floe. His terrible passage had taken months before he was rescued hundreds of miles down the strait by hunters. Alika tried to remember what Miak had said: "Get rid of the dogs. You'll be lucky to feed yourself. Toss them overboard. They'll run for home and alert the village. Build yourself an

iglu.

Watch out for bears. Don't go outside unless you have a rifle..."

Shore at this point was still only fourteen or fifteen feet away from their floe. Alika quickly unharnessed all the dogs except Jamka and pushed them into the water.

Nanuks,

polar bears, were always hungry, and Jamka would be the best defense against them. He knew their strong odor.