The Last Spike: The Great Railway, 1881-1885 (55 page)

Read The Last Spike: The Great Railway, 1881-1885 Online

Authors: Pierre Berton

Van Horne replied to Wiman’s complaints in a spirited letter to J. J. C. Abbott, the company’s counsel:

“I do not like to write in anger, but the whole day has passed and I have hardly yet worked down to a suitable state of mind to answer your note of yesterday. I am appalled at Mr. Wiman’s impudence.… [He] wanted our telegraph system for next to nothing while I wanted full value for it, and I think I know what that is as well as he does.…

“Our Directors have not as yet seriously discussed our telegraph policy, but when they do, I shall strongly represent the great value of their telegraph privileges and implore them to protect, develop and utilize them to the fullest extent and advantage and not in any event to part with them for less than their full value, considering all their possibilities, and not to be seduced by Mr. Wiman’s soft words, deceived by his false words, or frightened by his bluster into discounting one cent in price or yielding one inch in advantage: and in my opinion the Western Union Company will not accomplish much in this matter until they set some honourable man at work upon it, which I am free to say Mr. Wiman is far from being. You have my full permission to forward this letter to him.…”

In mid-June, Van Horne decided that he must inspect the line between Lake Superior and Nipissing before making his journey to the Pacific coast. The inspection covered everything, right down to the quality of the coffee on the lake steamer

Alberta

. “The table was very fair,” Van Horne informed Henry Beatty, “except that the coffee was bad, being too weak until I spoke to the steward about it and poor in quality as well, containing a considerable percentage of burnt peas.”

Accompanied by the government’s engineer-in-chief Collingwood Schreiber, Van Horne, set down on Superior’s drab shoreline, took off on an eighty-two-mile walking trip to look over the stretch between Nepigon and Jackfish Bay. Van Horne was a corpulent man by this time, spending most of his days at a desk in Montreal, but he amazed Schreiber by his energy and endurance. After walking for miles through fire-blackened rock country the two men finally reached an engineer’s camp at dusk, limp and sore. Van Horne promptly challenged the chief engineer to a foot race. On their return journey by steam launch from Jack Fish Bay

to Red Rock, the boiler began to leak, but Van Horne would not be thwarted. He and Schreiber and the boat’s engineer paddled the launch through the wave-flecked waters of the lake, and when the engineer met with an accident the two companions paddled the rest of the way themselves.

Van Horne’s indefatigability gave rise to many legends. One story was told of a powerful miner who, hearing of the general manager’s almost supernatural powers, resolved to do in one day, hour by hour, exactly what Van Horne was doing. The experiment almost killed him; at the day’s end, so the story went, the miner had to be carried to bed, where he remained for several weeks in a state of collapse.

In the camps along Superior’s shore and later in the mountains, Van Horne fitted in easily with the workmen, engineers, and subcontractors, sitting up all night in poker sessions, swapping stories, and drawing caricatures. He probably preferred the workmen to some of the stuffier members of Canadian society with whom he was forced to put up from time to time. He often used to test acquaintances for their sincerity. He liked to sign one of his own paintings with the name of Théo Rousseau, a fashionable French artist who was then in vogue, and listen sardonically to the ooh’s and ah’s of pretentious guests who praised his judgement. Later, when a nickel cigar was named for him, he invented “the cigar test.” His butler would remove the bands of a hundred Van Horne cigars, place them in an expensive humidor, and wheel them around to male guests after a dinner party. He had little use for those who drew deeply, praised the aroma, and remarked on the exquisite flavour of Havana tobacco.

He was often pestered by members of the nobility sent out by English financial interests to look over investment prospects in Canada; it was important to the company that he make a show of entertaining them, but when they became too annoying, he would squelch them with a routine known as “the trap.” Van Horne, who would himself one day refuse a peerage, would launch into a colourful account of how pioneer explorers, settlers, surveyors, and construction men had been so lonely for female companionship that they had taken up with Indian women. “As a result,” he concluded, “the country is thickly sprinkled with French Indian half-breeds, Scottish Indian half-breeds, Irish Indian half-breeds and Welsh Indian half-breeds.” The visitor usually rose to the bait: “You mean to say there are no English Indian half-breeds?” Van Horne supplied the squelch: “Well, after all, Sir, the squaws must draw the line

somewhere.”

His power, by 1884, was enormous. One rather profligate English peer,

Lord Dunmore, whom Van Horne must have suffered and perhaps squelched, said of him: “I don’t know a man living who exercises the patronage that man does at this moment. No other man commands the same army of servants or guides the destiny of a railway over such an extent of country.” Dunmore was perhaps a little jealous; he had tried to secure the contract to build the railway from John A. Macdonald in 1880. But he spoke truly. Van Horne, “the ablest railroad general in the world,” was in charge of the equivalent of several army divisions. At the same time he continued to indulge his various exotic tastes. His collection of Japanese porcelain was rapidly becoming the finest in the world; it was chosen carefully to illustrate historically the development of the art. He liked to demonstrate his connoisseur’s skill, especially when in a dealer’s shop for the first time. He would have himself blindfolded and, as each piece was put into his hands, he would name the artist, place of origin and approximate date, using only his sense of touch; he managed to be right about seventy per cent of the time. His taste extended to French paintings (he collected Impressionists long before they were popular or valuable) and to the design of

CPR

stations. When he discovered, to his chagrin, that his architects had designed the Banff Springs Hotel so that it faced away from the mountains, he personally sketched in a rotunda that could redress the oversight. The famous station at Sicamous in British Columbia, which rose like a trim ship from the lake’s edge, and the log station houses and chalets in the Rockies and Selkirks were also his idea. He scribbled a sketch on a piece of brown paper and turned it over to a designer with a brief order: “Lots of good logs there. Cut them, peel them, and build your station.” Thus in various subtle ways did Macdonald’s “sharp Yankee” help to transform the face of his adopted land.

5

The Pacific terminus

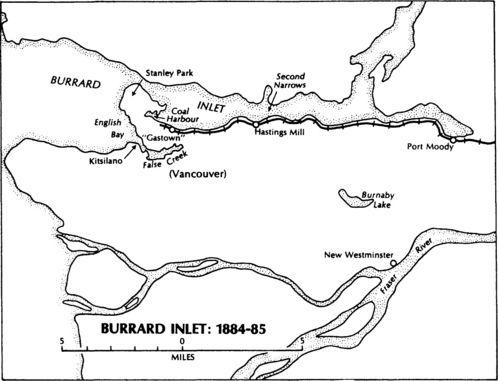

Van Horne’s expedition to British Columbia was finally arranged in late July, and on August 4 a distinguished party arrived at Victoria and moved swiftly across the Strait of Georgia to Port Moody, then designated as the terminus of the transcontinental line. The little village, perched on the rim of a narrow bank at the head of Burrard Inlet, was basking in the glow of optimism brought on by the unquenchable belief that it was to become the greatest metropolis on the Pacific coast. Until the summer of

1882, the site had been unbroken forest. When Van Horne arrived – with ships emptying their holds of steel rails, with the new railway terminal wharf heaped with supplies, with streets being hacked out of the bush and gangs of men at work grading the track towards Yale – the community was enjoying a mild boom.

“Port Moody … has no rival,” exclaimed the

Gazette

, the settlement’s pioneer newspaper. “There is no place upon the whole coast of British Columbia that can enter into competition with it … these declarations are sweeping but incontrovertible.”

The paper could hardly wait for Van Horne to arrive in order that the new metropolis could be laid out. It reported that the general manager would decide on the construction of a sea-wall as well as a new wharf, station houses, roundhouses, and machine and blacksmith shops. The

Gazette

became carried away by the magnitude of it all and began to envisage gigantic markets, theatres, churches, and paved streets (“The grades … should be fixed as soon as possible”) as well as “steamers from all quarters arriving hourly” and hotels, shops, and warehouses rising “like magic.” It was important, the editor noted, that the position of public buildings be carefully chosen, “with a view to the convenience of the great population soon to occupy the site of Port Moody.”

It was all tragically premature. In Victoria, Van Horne was disturbingly non-committal about Port Moody as a terminus. Before making a decision, he said, he wanted to visit the mouth of Burrard Inlet and examine its geography. There were two settlements straggling along the inlet, the tiny community of Hastings, surrounding the mill of that name, and another properly called Granville but dubbed “Gastown” after a former saloonkeeper, John “Gassy Jack” Deighton.

Van Horne did make one thing clear: wherever the terminal was situated, a large city would spring up second only, in his opinion, to San Francisco. The

Gazette

remained trenchantly optimistic. It conceded that there might be a branch line to Coal Harbour at the inlet’s mouth by way of Burnaby Lake, but insisted that the real terminus would remain at Port Moody. In spite of this, there was a thread of dark suspicion running through the article which referred, vaguely, to the potential enrichment of “the local land grabbers commonly called ‘ministers.’ ”

Van Horne, together with the Premier of British Columbia, William Smithe, and the ever-present realtor Arthur Wellington Ross, late of Winnipeg, arrived at Port Moody on the evening of August 6. The Elgin House, where the party stayed, was illuminated in their honour and decorated with flags, evergreens, and a variety of welcoming banners proclaiming

that Port Moody really was the western terminus of the line. That evening the general manager was met and interviewed by most of the prominent citizens. He kept his own counsel; he could, he said, express no opinion on the matter of the terminus. Nevertheless everyone believed that he had made up his mind in favour of Port Moody. As the

Gazette

reported: “It is his opinion that a city of 100,000 inhabitants will exist at the western terminus of the

C.P.R

. in a few years, and though he made no direct reference as to the exact location of that future city, yet it was not hard to infer that Port Moody was in his mind’s eye at the moment.”

Nothing could have been further from the truth. Van Horne’s immediate reaction to Port Moody was that it would not do. There was no room on that crowded ledge for a substantial city. The railway alone would require four hundred acres of level ground, and even that much space did not exist. To reclaim it from the tidal flats would cost between two and four million dollars. But, as the general manager learned the following day when he travelled to the mouth of the inlet by boat, there was plenty of level ground in the vicinity of Coal Harbour and English Bay. If Van Horne could persuade the provincial government to subsidize the continuation of the line from Port Moody, then it was his intention to build the terminus at that point. Two days later, the New Westminster

Columbian

, whose editor, John Robson, had considerable real estate holdings in the Coal Harbour area, made it clear that Van Horne had come to a decision: “Without discussing the branch further, he thought it proper to say it was the company’s intention to carry the line to Coal Harbour or some point in that vicinity.… The Syndicate had applied to the Provincial Government for a grant of land in the vicinity of Coal Harbour for a terminus, and if the grant were made they would raise money on these lands and extend the line.”

In Port Moody, the response to this fairly clear statement of intent was one of disbelief and fury. The

Gazette’s

attitude was that the

Columbian

had invented the tale. Van Horne’s alleged statement it said, was “the most extraordinary … that ever fell from the lips of a man in his position.” It was “as choice an assortment of cast iron lies as it has been our lot to meet in a journalistic experience of 7 years.” It was an “idiotic report.” The editor of the

Columbian

had been “played for a sucker.” It was clearly a wicked paper: “… truthfulness and honesty form no part of its creed.”

Van Horne’s decision ensured the swift decline of the little settlement at the head of the inlet. As the truth began to dawn upon them, Port Moody’s merchants sent off petitions of protest. These were in vain; the general manager could not be moved. He was already planning to name

the new terminus Vancouver. It is said that one reason he chose that title was because his own name bore the prefix “Van,” but such reasoning is dubious. The proximity of Vancouver Island was certainly a factor; it helped to identify the position of the new terminus geographically in the minds of world travellers. More than that, Van Horne, the romantic, wanted to give his new metropolis a name he considered worthy of its future – that of a daring explorer who had sailed those shores long before any railway was contemplated. “… the fact that there is an insignificant place in Washington Territory named Fort Vancouver should not in my opinion weigh in the matter,” he told Arthur Wellington Ross, who was acting as the railway’s agent in real estate on the site. “The name Vancouver strikes everybody in Ottawa and elsewhere most favourably in approximately locating the point at once.”