The Last Spike: The Great Railway, 1881-1885 (51 page)

Read The Last Spike: The Great Railway, 1881-1885 Online

Authors: Pierre Berton

In Michipicoten, the vigilante gang that ran the town was actually headed by the former police chief, Charles E. Wallace, one of whose henchmen, Harry Cleland, was an escaped convict from Jackson, Michigan. In October, 1884, the gang attempted to shoot the local magistrate, whose life had been frequently threatened. He took refuge in the construction office, ducking bullets that were fired directly through the walls. A force of Toronto police was called to the scene to restore order. They arrived on October 23 and were met at the docks by a rowdy crowd that would give them no information as to the identity of the culprits. Some persons among the throng on the dock were members of the gang; the others were too terrified to talk, believing that the police would fail in their mission and that on their departure informants would be punished.

The police made their headquarters in a local boarding house, and, after the mandatory four o’clock tea, set out to apprehend the instigators of the attack on the magistrate. By nightfall they had seven prisoners in custody. As a result, the boarding house became the target of hidden riflemen who pumped a fusillade of bullets into it, grazing the arm of the cook and narrowly missing one of the boarders. When the police emerged from the building, revolvers drawn, the unseen attackers departed. It was said that forty men armed with repeating rifles were on their way to rescue the prisoners. The police maintained an all-night vigil but there was no further trouble.

Meanwhile, about thirty prostitutes, driven out of Peninsula Harbour by Magistrate Frank Moberly, the redoubtable brother of Walter Moberly,

the British Columbia surveyor, had descended on Michipicoten, seeking refuge. They had no sooner debarked from the steamer than they learned that the police were in control. The gaudy assembly wheeled about and re-embarked for another destination.

The police destroyed one hundred and twenty gallons of rye whiskey, captured and dismantled a sailboat used in the illicit trade, and laid plans to capture the four ringleaders of the terrorist gang, including the expolice chief, Charles Wallace. After some careful undercover work they descended upon a nearby Indian village where the culprits were supposed to be hiding. The police flushed out the wanted men, but Wallace and his friends were too fast for them. A chase ensued in which the hoodlums, apparently aided by both the Indians and the townspeople, easily evaded their pursuers.

No sooner had the big city constabulary departed the following day with their prisoners than Wallace and his three henchmen emerged from the woods and instituted a new reign of terror. Wallace, “in true bandit style,” was carrying four heavy revolvers and a bowie knife in his belt and a Winchester repeating rifle on his shoulder. The four finally boarded the steamer

Steinhoff

and proceeded to pump bullets into the crowd on the dock before departing for Sault Ste Marie. Their target was actually the

CPR

ticket office and, more specifically, the railway’s agent, Alec Macdonald, who had taken refuge within it. Before the steamer departed Wallace and his friends had managed to riddle the building with a hundred bullets without, fortunately, scratching their quarry.

Frank Moberly arrived shortly afterwards with a posse and cleaned up the town, but Wallace himself and his partners were not captured until the following February, after a gunfight in the snow in which one of the arresting constables was severely wounded. Wallace was sentenced to eighteen months in prison. By the time he was released, the railway was completed and the days of the whiskey peddlers were over forever.

2

Treasure in the rocks

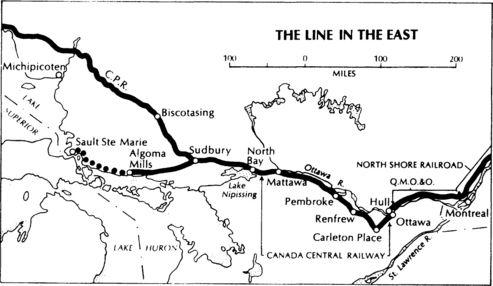

Between Thunder Bay and Lake Nipissing there was no single continuous line of track. The contractors, supplied by boat, were strung out in sections of varying length, depending on the terrain; indeed, some contracts covered country so difficult that only a mile was let at a time. For administrative purposes, the Lake Superior line was divided into two sections: the difficult section led east from Fort William to meet the easier section, which ran west from Lake Nipissing, the point at which the Canada Central, out of Ottawa, joined the

CPR

proper.

In the summer of 1882, a young Scot of eighteen named John McIntyre Ferguson arrived on Nipissing’s shore. Ferguson was the nephew of Duncan McIntyre, president of the Canada Central and vice-president of the Canadian Pacific – an uncle who knew exactly where the future railway was going to be located. The prescient nephew purchased 288 acres of land at a dollar an acre and laid out a townsite in the unbroken forest. He also built the first house in the region and, in ordering nails, asked the supplier to ship them to “the north bay of Lake Nipissing.” Thus did the settlement unwittingly acquire a name. By 1884, when the

CPR

established its “company row,” North Bay had become a thriving community. Ferguson went on to become the wealthiest man in town and, after North Bay was incorporated, its mayor for four successive terms.

North Bay was totally the creation of the railway. Before its first buildings were erected, the main institutions were located in railway cars shunted onto sidings. The early church services were held in these cars and the custom continued for some time until the first church was constructed in 1884. The preacher, an imperturbable giant of a man named Silas Huntington (whose son Stewart founded the town’s first newspaper), used an empty barrel, up-ended, as a pulpit and brooked no opposition from the rougher elements in his congregation. When two muscular navvies took exception to one of his sermons, Huntington quit his makeshift pulpit and started down towards them, preaching as he went. As he drew opposite the intruders he took one in each hand and dropped them

out the door without pausing for breath or halting the flow of his sermon.

Such

savoir-faire

was a Huntington trademark. There was another occasion during a service when his box-car church was parked on a siding on a hillside. Someone accidentally let the brake off and as Huntington was in the middle of his sermon, the car gave a jerk and began slowly, and then with gathering speed, to roll downhill. The car ran down to the main line and off to the edge of the new town while Huntington, without so much as a raised eyebrow, continued to preach. When he had finished, the congregation sang the doxology and walked back without comment.

The land between North Bay and Lake Superior was generally considered to be worthless wilderness. For years, the politicians who opposed an all-Canadian railway had pointed to the bleak rocks and stunted trees of the Shield country and asked why any sane man would want to run a line of steel through such a sullen land. The rails moving westward from North Bay cut through a barren realm, denuded by forest fires and devoid of all colour save the occasional sombre russet and ochre, which stained the rocks and glinted up through the roots of the dried grasses on the hillsides. These were the oxides of nickel and copper and the sulfides of copper and iron, but it needed a trained eye to detect the signs of mineral treasure that lay concealed beneath the charred forest floor.

By the end of 1882, the rails of the Canada Central, following the old voyageurs’ route up the Ottawa and Mattawa rivers from Pembroke, had crossed the height of land and reached Lake Nipissing. By the end of 1883 the first hundred miles of the connecting

CPR

were completed. Early that year the crudest of tote roads, all stumps and mud, had reached the spot where Sudbury stands today. Here, as much by accident as by design, a temporary construction camp was established. It was entirely a company town: every boarding house, home, and store was built, owned, and operated by the

CPR

in order to keep the whiskey peddlers at bay. Even the post office was on company land and the company’s storekeeper, Stephen Fournier (who was to become Sudbury’s first mayor), acted as postmaster. Outside the town, private merchants hovered about, hawking their goods from packs on their backs. It was not until 1884 that the most enterprising of them, a firm-jawed peddler named John Frawley, discovered that the

CPR

did not own all the land after all; the Jesuit fathers had been on the spot for more than a decade and held title to adjacent property. Frawley leased a lot from the religious order for three dollars a month, opened a gents’ furnishing store in a tent, and broke the company’s monopoly. By then a mining rush was in full swing and Sudbury was on its way to becoming a permanent community.

The first men to examine the yellow-bronze rocks in the hills around the community made little or nothing from their discoveries. The earliest to take heed of the mineral deposits was probably Tom Flanagan, a

CPR

blacksmith, who picked up a piece of ore along the right of way about three miles out of town and thought (wrongly) that he had found gold. He did not realize that he was standing not only on a copper mine but also on the largest nickel deposit in the world. Flanagan did not pursue his interest, but John Loughrin, who had a contract for cutting railroad ties, was intrigued by the formations and brought in three friends, Thomas and William Murray and Harry Abbott. In February, 1884, they staked the land on what became the future Murray Mine of the International Nickel Company. It subsequently produced ore worth millions, but not for the original discoverers.

Other company employees became millionaires. One was a gaunt Hertfordshire man named Charles Francis Crean. Crean, who had been working on boats along the upper Ottawa carrying provisions to the construction camps, arrived on the first work train into Sudbury in November, 1883. At that time the settlement straggling along the tote road had yet to be surveyed; buildings were being thrown together and laid out with no thought for the future. The first hospital, built of logs by the

CPR

construction crews, turned out to be in the middle of what was later the junction of Lorne and Elm streets. The mud was so bad that a boy actually drowned in a hole in the road opposite the American Hotel. Crean, on his arrival, walked into the company store and noticed a huge yellow nugget being used as a paperweight by the clerk behind the counter. The clerk said the ore was probably iron pyrites – fool’s gold – but he let Crean have a piece of it. Crean sent it to a chemist friend in Toronto who told him it was an excellent sample of copper. In May, 1884, Crean applied for a mining claim and staked what was to become famous as the Elsie Mine.

A month later, the observant Crean spotted some copper ore in the ballast along the tracks of the Sault Ste Marie branch of the railroad. He checked back carefully to find where the material had come from and was able to stake the property on which another rich mine – the Worthington – was established. Later he discovered three other valuable properties, all of them steady producers for years.

A week after Crean staked his first claim, a timber prospector named Rinaldo McConnell staked some further property which was to become the nucleus of the Canadian Copper Company’s Sudbury operation – the forerunner of the International Nickel Company. (It was copper, of

course, that attracted the mining interests; nickel had few uses at the time.) Another prospective millionaire that year was a railway construction timekeeper named Thomas Frood, a one-time druggist and schoolteacher from southwestern Ontario who acted on a trapper’s hunch and discovered the property that became the Frood Mine, perhaps the most famous of all.

For every fortune made at Sudbury there were a dozen lost. Well before the staking rush – in the fall of 1883 – Andrew McNaughton, the first magistrate of the new settlement, arrived with the

CPR

construction crew to maintain the law and keep the camp free of liquor. McNaughton went for a stroll in the hills and became lost in a heavy fog. The search party that found him also picked up some copper-stained rocks. The newly arrived physician, Dr. William H. Howey, sent some of those rocks to Alfred Selwyn, the director of the Geological Survey of Canada and perhaps the ranking expert in the nation on the subject of mineral deposits. Selwyn pronounced the samples worthless and Howey threw them away. Later it developed that McNaughton had been standing on the site of the Murray Mine when his searchers found him. From then on, Howey had an understandable contempt for geological experts.

But then the story of northern Ontario mining is the story of happenstance, accident, and sheer blind luck. Sudbury itself was an accident. The line was supposed to be located south of Lost Lake, but the locating engineer, William Allen Ramsay, took it upon himself to run it north, an act which caused his boss, James Worthington, to rename the body of water Lake Ramsay (later spelled “Ramsey”). Worthington himself named the town Sudbury Junction after his wife’s birthplace in England. He had not intended to use such an unimportant spot on the map to honour his spouse – for Sudbury at the time was seen as a transitory community. However, the station up the line that was expected to be the real centre of the area had been named for Magistrate McNaughton, and Worthington had to settle for the lesser community. He was not the only man to underestimate the resources of the Canadian Shield. Long before, when John A. Macdonald had talked of running a line of steel through those ebony scarps, Alexander Mackenzie, the Leader of the Opposition, had cried out that that was “one of the most foolish things that could be imagined.” Edward Blake had seconded the comment, almost in the same words. Right up until the moment of Sudbury’s founding, some members of Macdonald’s cabinet, not to mention a couple of the

CPR’S

own directors, were opposed to such madness. It was only when the land began to yield up its treasure that the fuss about the all-Canadian line was stilled.