The Last Speakers (17 page)

Authors: K. David Harrison

The story ends abruptly, though on a happy note. It is a monument of oral literature, and we can only speculate how ancient it may be. It could easily be of the same antiquity as canons of Western literature like the

Odyssey

. It shows hallmarks of being stitched together from many different stories, indicating repeated retelling and reinterpretation. Alongside ancient motifs (vampires, an underworld quest), we see some modern touches, such as vodka and guns. It has been passed down only orally, always adapting, told around the campfires at evening. In the small birch-bark huts the Chulym once lived in, with blocks of ice for windows, stories like this would have provided the only entertainment during long winters.

How did these stories almost slip away? Why were they hidden? The Chulym shaman story was hidden out of fear, because native religion was banned. Vasya's writing was hidden out of shame, because he was made to feel inferior for his ethnicity and language. And the ancient underworld quest story of the “Three Brothers” was hidden partly by neglectâas new forms of entertainment like television replaced storytellingâand partly by politics, as the Chulym were never allowed to write their stories down in books or teach them in schools.

Whatever the reason for hiding a language, silencing a story, or subduing a song, on our linguistic expeditions we do the spadework that brings these hidden words back to light. At the very least, we can give them a continued existence in the pages of books or in digital archives. Beyond that, we hope to encourage a new generation to continue telling and singing them. Without our human stories, as diverse or as similar as they may be across time and space, we are not fully ourselves.

SIX DEGREES OF LANGUAGE

The entire world needs a diversity of ethnolinguistic entities for its own salvation, for its greater creativity, for the more certain solution of human problemsâ¦indeed, for arriving at a higher state of human functioning.

âJoshua A. Fishman

THE FAMOUS TRIVIA GAME

“Six Degrees of Kevin Bacon” was designed to show that all people on Earth can be connected by just a few links. The odds are very good that you know someone who knows someone who knows someoneâ¦who knows Kevin Bacon (or anyone else). Every person in the “human web” is linked to every other person, if this principle holds true, by a chain of no more than five people. What started out as an amusement has become a serious research effort at the heart of the emerging science of social networks. We are all connected, and it is language, not film, that plays the greatest role in spinning the links between us.

Environments like Facebook provide an easily traceable map of a person's social networks, the geography of their friendships. If you “friend” me, I can look and see who all

your

friends are. But the network exists, and governs all our lives, even if we do not have Facebook to visualize it for us. Entire societies are built upon the foundation of social networks, and we are all constantly kept busy with their construction, repair, and revision. Social networks transmit information, allow us to feel we belong to various communities, and, like language or ethnicity or social class, help us to draw a firm (even if invisible) boundary between “us” and “them.” Humans are driven to separate themselves and segregate into groups, and everyone belongs to multiple social groups that inspire varying degrees of allegiance. Languages are one of the most effective ways to signal group membership, and we are hypersensitive to even minor differences in pronunciation and vocabulary. If I say “pop” instead of “soda” in New York, I instantly, with just that one word, signal my status as an outsider to the local community.

Papua New Guinea, with its 800-plus languages, is the extreme example of how languages signal group membership. For reasons we don't fully understand, a relatively small population of seven million people, belonging to small groups in constant contact with other groups, has, instead of converging on a common language, kept a massive number of distinct ones. This unique situation sheds light on some mysteries about how languages function in social networks.

If you use Facebook, currently the premier social networking site, you may have drawn a “friend wheel,” a visual representation of all your friends. You are at the center of the wheel, and you (possibly) know all your friends personally. The more interesting question is which of your friends are connected to each other. Clusters of friends appear together on the wheel, which is not surprising, since, for example, everybody in my high school senior class of 60 knew each other. More surprising are links between two friends who happen to know each other and don't know anyone else in common except me. We form a triad. And then, because we live such mobile lives, there are always many friends on my wheel who know absolutely no one else in my life and may never meet any of them. I am their one degree of separation.

I enjoyed periodically redrawing my friend wheel on Facebook, but at 600 friends, I reached the upper limitâthe program cannot calculate more than that. I imagined what life would be like if 600 were the actual upper limit of friends one could have (of course, no one can have 600 really close friends, but I'm including casual friends, some colleagues, and my banker and barber here). Now imagine what would happen if we lifted my entire friend wheel, with all 600 people attached, and put us on a desert island. We would quickly form a society, with all the soap opera intimacies,

Lord of the Flies

rivalries, and

Survivor

politics. The wheel would grow many new spokes, as the 600 became more densely networked until eventually everybody knew everybody. At that point, the wheel would tell us nothing useful. We would be a maximally densely networked society, each member having zero degrees of separation. The thought is enough to make me claustrophobic. Since friendship is not transitive, I imagine many of my friends would end up hating each other (though some might fall in love, counterbalancing that). It would no longer be a friend wheel but simply a “people in my society” wheel.

While there's nothing magic about the number 600, or my imaginary dense network, that number approximates the total number of speakers of many of the languages in New Guinea and elsewhere. What happens when an entire language is spoken exclusively and constantly by 600 people who all know each other (they may not all talk to each other, but they all live in the same village where they

could

converse with, or overhear, everyone else's speech)? In 2009, our Enduring Voices research team arrived in Papua New Guinea, land of more than 800 languages, to delve into these questions.

1

Panau (which means “give me”), a small language in Madang province, nearly fits the “friend wheel” profile. Spoken in just one small seaside village of 600-plus souls in Papua New Guinea, Panau has the densest possible network. Imagine what it must be like to speak such an exclusive language, with zero degrees of separation between every speaker. One direction such a language could take is that it could be very conservative, changing very little over time, thus having little or no variety (nobody from one end of the village to another has a different accent or dialect, and there are no “pop”-vs.-“soda” disputes).

On the other hand, we can imagine such a language changing very quickly, because it would be much easier to introduce new words. A Panau speaker could wake up one morning and notice a new (to him) object, say, an iPod that a neighbor brought home from the market town. With little effort, he could declare it a

“babala,”

and that new word might catch on and become the name everyone called it. Even if they decided to call it an “iPod,” that would be a new loanword and could very quickly become known and used by every single speaker. In English, such innovations take much more time to ripple through the vast and dispersed population of speakers, even with the help of mass media. There are surely English speakers alive today who have not (yet) heard the word “iPod,” though they must live fairly isolated lives. Many more will not yet have heard “Facebook” or “Napster.” Yet a Panau speaker could stand in the center of his village and shout the new word, broadcasting with complete efficiency to nearly every single speaker at once.

So which is it? Do small, densely networked languages accelerate their evolution, or do they put the brakes on? Do they change rapidly or hardly at all? And what does the special character of very small languages tell us about human nature, social networks, and the future?

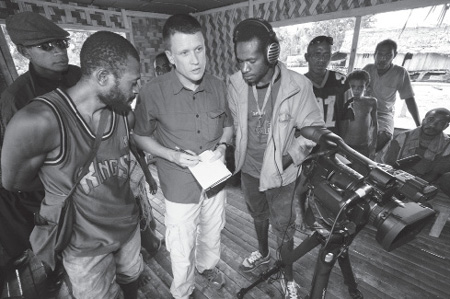

The author working in Matugar village, Madang province, Papua New Guinea, 2009, with Panau speakers Hickey Willie and John Agid. Panau is spoken by about 600 people, making it an excellent example of a very small, densely networked language.

ALL FOR ONE AND ONE FOR ALL

As he hung the shell necklace around my neck, Peter Kosi told me, “Don't forget us.” He looked at me piercingly with his right eye, turning his left eye, blinded and white, away from the camera. Peter was dressed in the full finery that the Karim people reserve nowadays for rare initiation dances, with a woven vine apron in the front, fronds of grass in the back. His elaborate shell necklace and a head ornament with pig tusks marked him as a man of high status, and when he spoke, it became clear why. Bare-chested to show off his powerful upper body, he boasted a physique honed not at the gym but in the jungleâby countless hours chopping bamboo, rowing canoes, digging soil with a wooden spade, and hefting logs.

Next to Peter stood George, a younger man with an even more impressive physique, and with a full pattern of ritual scars covering his back, chest, and upper arms. Intricate patterns of bumps, some protruding almost a half inch and several inches in length, formed what resembled a crocodile's skin superimposed upon his own flesh. It was as if a man had merged with a crocodile. Though he was a modest, soft-spoken man, George's scars signaled status and placed him among the most prominent members of his age group. He told me how he had been one of only two volunteers from his village who answered the call of distant clan brothers to be initiated into the crocodile clan.

In Papua New Guinea, people belong first and foremost to an ethnic group, identified strongly with a local place and languages, and so George was a Karim person. He also belonged to the nation as a whole, as a citizen of Papua New Guinea. But in between local and national identity, everyone also belongs to a clan. This requires special allegiance and bestows distinct privileges. A member of any clanâwhether the pig, crocodile, cassowary, or eagleâhas the right to travel to any distant village, perhaps even a place where he cannot communicate in the local tongue, and to be welcomed, housed, and fed by members of his same clan.

To prove his worth as an initiated crocodile clansman, George and one other village mate had traveled to a distant village for an arduous six-week initiation. He endured hundreds of cuts, using a technique that embedded dirt into the wounds to cause permanent bumps. His only anesthetic came from plants known to the local healers for their medicinal properties. His initiators stuffed large amounts of the leaf into his mouth both to alleviate pain and to keep him from screaming. While he had left Yimas village as a handsome young teenager on the brink of manhood, George returned a hardened veteran and initiated adult man of his clan, ready to marry, to father children, and to take on a leadership role in his village.

Wherever George goes, he is instantly recognized and taken care of by clan members. He has mutilated his flesh to show respect for his totem, the crocodile. This level of dedication far exceeds the tattooing of a loved one's name on your arm or devotion to a religious cult, and probably cannot be understood by outsiders who do not abide in the faith of the crocodile and do not share a worldview in which river spirits determine human destinies.

Karim religion is in decline, and important rituals are rarely performed these days. As we observed on the fringes, a powerful circle of dancers formed in the main square of the village known as Yimas 2. Wearing body paint, shell ornaments, and grass skirts, they formed two rings. Women took the outermost ring, men the inner. At the center, two figures enclosed completely in body masks wove their dance steps, swaying and plunging. Time was kept by a steady pounding on a large slit drum, echoed by small hand drums held by the male dancers.

This was an initiation ritual, performed out of time and place and entirely unfamiliar to the village's youngest residents. Originally this would have been performed inside a spirit house, with women dancing outside and men within, the teenage male initiate brought into the spirit house for his coming-of-age ceremony. But this village no longer had a spirit house. The village headman explained to us how the ritual had fallen into disuse and how glad he was to see it being performed, even if partly for show. The intensity of the dancers, as they sweated and chanted, and their obvious sense of cultural pride indicated this was no mere performance. Despite the infrequency of the initiation ritual and the fact that it took place at the initiative of our National Geographic team, the dance evidenced a certain resilience of belief. Even without a spirit house, the 40 participants had spent hours adorning and painting themselves, and they took great care to perform the ritual correctly.

Just upstream, in the sister village Yimas 1 (Google Earth location S 04° 40.871' E 143° 33.011'), a newly constructed spirit house presents a powerful visual icon of the crocodile. As you pass under the doorway into the spirit houseâa place only men may enterâjust over your head you see a carved wooden woman with her legs spread wide, giving birth to a crocodile. The crocodile has emerged halfway from the womb, its head and forelegs dangling downward. This painful imagery, perhaps grotesque to Western eyes, displays one of the most sacred totemic principles of the Karim people. Their creation myth begins with the birth of a crocodile. It introduces and sustains life and is to be worshipped and respected, as well as feared and imitated.

Just as the spirit house re-creates the totemic imagery, and the ritual dancing and drumming re-create the spirit narrative, the Karim language, now severely endangered, sustains the complex clan system and the mythology that underlies their religion. “Our children are starting to forget our language,” Peter Kosi told me, explaining how the childrenâwho attend school with children from a different tribe located just downstreamâspeak mostly Tok Pisin. “We need a linguist to come to our village and help us, before our language disappears.” Indeed a linguist

had

worked among the Karim people, and even published a thick grammar book,

2

which they took great pride in. But that had been two decades ago, and the book itself was written for a scientific readership, in highly technical language, and was not available or useful for teaching the language to children.

Children are empowered decision-makers about whether to keep or abandon a language. When placed into a setting, such as a school, where their home language is not valued or encouraged, they may react by shifting away from it to speak the more dominant language. But it does not have to be so, as children can easily become bilingual. In the case of Karim children, school is the vector for language shift, specifically a school setting where they study with children from another tribe. One of the most powerful forces of ethnic identityâlanguageâcan vanish in a generation. It's certainly fair to ask: “Aren't kids better off shedding a small local language and becoming globally conversant citizens?” In response, wouldn't an even better scenario be kids who increase their brainpower by being bilingual and enjoy the benefits of both a close-knit ethnic community and a sense of national or global participation?