The Last Speakers (7 page)

Authors: K. David Harrison

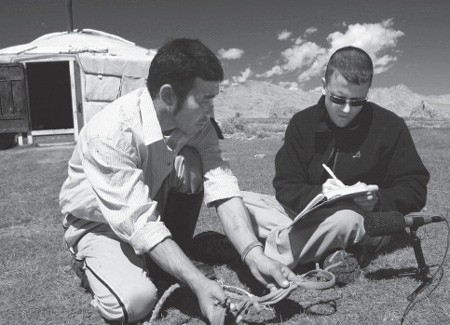

Nedmit demonstrates for me how to make a horse hobble.

Nedmit performed the slaughter with a quiet intensity. No one joked, sang, or talked loudly during it. After all, this was a sheep they had raised by hand and cared for since birth and even bestowed a pet name upon. Preparations included filling a bucket with fresh water and sharpening a knife against stone, a rasping that sent the family dogs into a state of agitated expectation. The sheep seemed to know something was afoot as well, and they bolted into the security of their fenced enclosure.

One of the fatter sheep suddenly found itself detained, its hind leg grasped firmly and pulled upward. In vain, it dug in its other three legs to resist being pulled backward out of the pen. A clean spot on the ground was chosen, as usual quite close to the door of the yurt in order to be close to the stove.

Nedmit then flopped the sheep onto its back and bound its front legs with a short cord. He held a back leg under his left knee and had his son hold the head down by its horns. An experienced man can do the entire job solo, but teaching the skill to his son (for sheep can be slaughtered only by men among the Monchak) was part of the routine.

Parting the sheep's wool just to the left of the breastbone, Nedmit made a careful four-inch vertical incision through the hide, exposing the inner lining of fat that contains the internal organs. The whitish-pink fat bulged out slightly through the incision, but no blood spilled out. The sheep lay still, making no sound. Nedmit formed his right hand into a point by pressing the tips of his five fingers together and drove this point, spearlike, deep into the sheep's abdomen, not through the middle, but down along the inside of the rib cage to the spine, where he felt out the main artery with his forefinger and plucked it once, severing it. He removed his hand slowly, again taking care not to spill a single drop of blood. The sheep passed into a coma within seconds. Being both Buddhists and animists, the Monchak take great care not to inflict unnecessary suffering on any living being, and this was evident in the way they slaughtered the sheep. Before proceeding, they waited for the sheep to expire fully. Within a minute, the sheep's eyelids no longer twitched when Nedmit flicked his finger against them: the definitive sign of death.

The first stage of cutting up the carcass began. The legs were snapped off at the knee joints, making loud, snapping sounds. The legs would not be eaten, but set aside for the sheep's head soup. Nedmit expanded the original incision in four directions, again cutting only the outer hide, not nicking the layer of fat and flesh beneath it and spilling not a drop of blood. He then stripped the hide back in four directions and weighted it down at the corners with rocks, creating a clean space on which the rest of the carving was performed. The sheep was now shed of its skin, lying belly up and glistening white and fatty. Only a tiny patch of wool remained on the sheep, a piece about three inches wide and eight inches long covering the sternum. The removal of this piece marks an important symbolic moment in the process and is done with the greatest reverence. It must not be touched with the hands. Instead Nedmit leaned carefully over the sheep and grasped the end of the strip of wooly hide with his teeth. He then rocked backward slowly, pulling the strip away from the carcass. Only then could he touch it with his hands, and he handed it carefully to Nyaama, his wife. She would either offer it to the fire or keep it inside the yurt in a neat little pile along with the head and feet until after the sheep was consumed.

Demdi, a Monchak Tuvan, slaughters a sheep in the traditional way.

Now the second stage of the carving could begin. Nedmit cut into the abdomen, making a larger opening in the center and two smaller slits along the bottom. Into these slits he inserted the ends of the sheep's lower leg stumpsâwhich act as natural springs, stretching the abdominal opening wide so that there is sufficient space to work. With the internal organs fully exposed, a number of strategic cuts were made in a particular order. These allowed the various organs to be removed, again in a particular order and with surgical precision.

I grabbed my field notebook and began asking questions. I wanted to know the name for each internal organ and part, as well as the verbs that described the actions. I scribbled Monchak words in my notebook, learning their terms for liver, kidneys, gallbladder. The latter contains poisonous bile and must not contaminate the meat. It is a taboo object and must be hung up to dry inside the yurt near the ceiling, where it serves to propitiate the spirits. I felt a bit queasy at the smell of fresh sheep guts, but at the same time I was mesmerized by the ritual. By the end, I would collect more than 50 new words in my notebook. At the same time, I felt like an adopted son who had been taught one of the most important activities in Monchak life.

The stomach was carefully lifted out. It was full of rank-smelling half-digested grass, and I recoiled at the stench. A critical moment came when the stomach was severed; at that instant, it had to be handed over to Nyaama, and from then on could only be handled by women. Nyaama and Golden New Year took it to down the riverbank, where they emptied it, turned it inside out, and washed it thoroughly.

Next came the large and small intestines, carefully uncoiled and placed on a specific type of flat rectangular wooden tray. They too had to be prepared by the women, methodically turned inside out, emptied of the little balls of dung they contained, and washed thoroughly.

The end result, about an hour later, was a large bubbling cauldron of what the Monchak call “hot blood,” a stew of all the carefully prepared internal organs. The cleaned stomach became a bag into which blood was poured (it would congeal into a blood pudding). The meat was not eaten yet; it would be hung on the walls to dry and consumed over the next two weeks. The sheep's massive fatty tail, weighing at least five pounds, was the dish that would be consumed firstâand it was offered to me, the guest of honor. I was given a knife and sliced off a small wedge of fat to present to each family member, in descending order of age, as protocol demands.

Afterward, as I lay in my sleeping bag in the yurt, my stomach full of sheep organs and fat, I was amazed at how much I had experienced in just one day. I'd been befriended by an entire extended family, participated in a sheep slaughter, helped collect dung for the fire, and helped herd, corral, and milk the goats. Above all, my brain was buzzing with information, new words for dozens of objects that only yesterday I had not known existedâfor example, the sheep's bile sac or the chunk of fat on the sheep's tail. I had a new appreciation for the intricacies of naming objects in a culture where knowledge means survival. Collecting words during a sheep slaughter could not have been further from a dry academic discussion of how a grammar is constructed. Yet it revealed a richness and precision about the Monchak way of talking, indeed of how they apprehend the world.

THE LANGUAGE AND THOUGHT DEBATE

My time among the Tuvans, the Tofa, and the Monchak made me realize just how many important concepts they possess that have no exact counterpart in any other language. This reminded me of a long-standing debate among scientists about the relation between language and perceived reality. As biologist Brendon Larson has noted: “There are multiple challenges in examining this linguistic link between ourselves and the natural world because such reflection is akin to a fish reflecting on the water in which it has lived its entire life. We cannot escape language to look at it.”

4

Scientists and philosophers have long speculated: Does the language we speak impose certain categories, pathways of thought, or filters that affect the way we perceive the world? Or is the language we speak irrelevant, exerting no effect upon the way we think? This thesis was classically formulated in the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis, as described by Benjamin Lee Whorf:

We dissect nature along lines laid down by our native languages. The categories and types we isolate from the world of phenomena we do not find there because they stare every observer in the face; on the contrary the world is presented in a kaleidoscopic flux of impressions which has to be organized by our mindsâand this means largely by the linguistic system in our minds.

5

Taken in its strong form, linguistic determinism effectively means that language determines realityâthat it determines what we can think and therefore what we can say.

The strong form of the thesis has been largely discredited, though a weaker formâthe theory of linguistic relativity, which holds that language

influences

our experience of realityâhas been mostly accepted.

6

Another way to formulate this is that language doesn't tell us what we

can

say, rather it tells us what we

must

say.

7

Instead of thinking of language as a kind of blinder that prevents us from seeing or saying certain things, we can think of it as a magnifying glass that focuses our attention, requiring us to pay attention to certain details. So, for a Tuvan speaker, because he must know the direction of the river current in order to say “go,” the language is forcing him to pay attention to river flow and to be aware of it at all times.

Languages may focus or channel our thoughts in particular ways. A speaker of the Carrier language must know the tactile properties of an object in order to say “give.” What is being given? Is it small and granular? Fluffy? Mushy? Liquid? Each type of material requires a different verb form for “give.” And so speakers must talk about tactile properties of objects. In many small ways, languages focus thought rather than limiting it.

No better example can be found than the controversial subject of how many words the Eskimo have for “snow.” A Google search for “Eskimo snow words” yields more than 10,000 hits. Deriding this as an example of bad science run amok has become somewhat of a game among linguists. A leading academic in his book

The Great Eskimo Vocabulary Hoax

stated unequivocally that the Inuit people of Alaska do

not

have many words for snow, and in fact have only about a dozen basic ones. The debunkers rely on this count to show that Inuit snow words are neither prolific nor special. This stance feeds into a more general agenda of asserting that all languages are equal and equally interesting to science.

Proponents of this view became so intent on debunking it that they spawned a new termâ“snow clones”âto mock all such statements that “The so-and-so people have

x

number of words for

y.”

Entire Web pages are devoted to listing mock Eskimo snow words that have imaginary meanings like “snow mixed with husky shit” or “snow burger.” Even Steven Pinker took up the issue in his book

The Language Instinct,

stating: “Contrary to popular belief, the Eskimos do not have more words for snow than English. They do not have four hundred words for snow, as it has been claimed in print, or two hundred, or one hundred, or forty-eight, or even nine. One dictionary puts the figure at two. Counting generously, experts can come up with about a dozen, but by such standards English would not be far behind, with snow, sleet, slush, blizzard, avalanche, hail, hardpack, powder, flurry, dusting, and a coinage of Boston's WBZ-TV meteorologist Bruce Schwoegler, snizzling.”

8

Sadly, the snow-cloners have missed the point. They have grossly underestimated the number of words by relying on very limited modern accounts and thinking that just because the number was inflated in the past by people who should have known better, the true count must be unimpressively low. As we will see, the number of snow/ice/wind/weather terms in some Arctic languages is impressively vast, rich, and complex. Furthermore, they have missed the forest for the trees, failing to see the importance of how words encode knowledge. Beyond the sheer numbers of words for natural phenomena like snow and ice, these languages demonstrate the complex ways in which words package information efficiently.