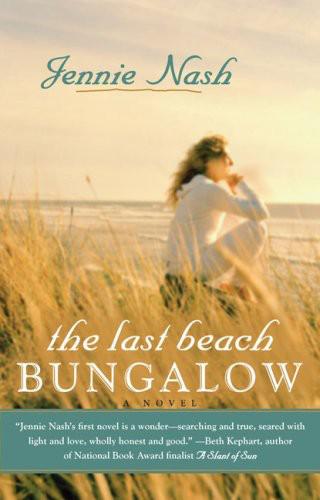

The Last Beach Bungalow

Read The Last Beach Bungalow Online

Authors: Jennie Nash

Tags: #Psychological Fiction, #Contemporary Women, #Dwellings - Psychological Aspects, #General, #Psychological, #Homes- Women-Fiction, #Psychological aspects, #Fiction, #Dwellings

Table of Contents

THE BERKLEY PUBLISHING GROUP

Published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Group (USA) Inc.

375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014, USA

Penguin Group (Canada), 90 Eglinton Avenue East, Suite 700, Toronto, Ontario M4P 2Y3, Canada

(a division of Pearson Penguin Canada Inc.)

Penguin Books Ltd., 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England

Penguin Group Ireland, 25 St. Stephen’s Green, Dublin 2, Ireland (a division of Penguin Books Ltd.)

Penguin Group (Australia), 250 Camberwell Road, Camberwell, Victoria 3124, Australia

(a division of Pearson Australia Group Pty. Ltd.)

Penguin Books India Pvt. Ltd., 11 Community Centre, Panchsheel Park, New Delhi—110 017, India

Penguin Group (NZ), 67 Apollo Drive, Rosedale, North Shore 0632, New Zealand

(a division of Pearson New Zealand Ltd.)

Penguin Books (South Africa) (Pty.) Ltd., 24 Sturdee Avenue, Rosebank, Johannesburg 2196,

South Africa

Published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Group (USA) Inc.

375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014, USA

Penguin Group (Canada), 90 Eglinton Avenue East, Suite 700, Toronto, Ontario M4P 2Y3, Canada

(a division of Pearson Penguin Canada Inc.)

Penguin Books Ltd., 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England

Penguin Group Ireland, 25 St. Stephen’s Green, Dublin 2, Ireland (a division of Penguin Books Ltd.)

Penguin Group (Australia), 250 Camberwell Road, Camberwell, Victoria 3124, Australia

(a division of Pearson Australia Group Pty. Ltd.)

Penguin Books India Pvt. Ltd., 11 Community Centre, Panchsheel Park, New Delhi—110 017, India

Penguin Group (NZ), 67 Apollo Drive, Rosedale, North Shore 0632, New Zealand

(a division of Pearson New Zealand Ltd.)

Penguin Books (South Africa) (Pty.) Ltd., 24 Sturdee Avenue, Rosebank, Johannesburg 2196,

South Africa

Penguin Books Ltd., Registered Offices: 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously, and any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, business establishments, events or locales is entirely coincidental. The publisher does not have any control over and does not assume any responsibility for author or third-party websites or their content.

Copyright © 2008 by Jennie Nash

All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced, scanned, or distributed in any printed or electronic form without permission. Please do not participate in or encourage piracy of copyrighted materials in violation of the author’s rights. Purchase only authorized editions.

BERKLEY

®

is a registered trademark of Penguin Group (USA) Inc.

The “B” design is a trademark belonging to Penguin Group (USA) Inc.

®

is a registered trademark of Penguin Group (USA) Inc.

The “B” design is a trademark belonging to Penguin Group (USA) Inc.

PRINTING HISTORY

Berkley trade paperback edition / February 2008

Berkley trade paperback edition / February 2008

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Nash, Jennie, 1964-

The last beach bungalow / Jennie Nash.—Berkley trade paperback ed.

p. cm.

The last beach bungalow / Jennie Nash.—Berkley trade paperback ed.

p. cm.

eISBN : 978-0-425-21927-0

1. Dwellings—Psychological aspects—Fiction. 2. Psychological fiction. I. Title.

PS3614.A73L37 2008

813’.6-dc22

2007024724

PS3614.A73L37 2008

813’.6-dc22

2007024724

Locatedness is not a science of the ground,

but of some quality within us.

—RICHARD FORD

but of some quality within us.

—RICHARD FORD

For Rob

Home is where you are.

Home is where you are.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The idea for this book came to me in a flash on a yellow school bus, and a whole busload of friends and associates have helped me bring it to life. Kristine Breese, my writing soulmate, read every single page of every single draft and made it better each time through her intelligence, spirit and generosity. Lisa Edmondson, friend and guru, guided me at a critical moment to see what the flash on the bus was really all about. Beth Kephart, novelist and pen pal, provided constant and poetic long-distance encouragement. My husband, Rob, gave me a living, breathing model of a loving husband. My children, Carlyn and Emily, talked about my characters at the dinner table as if they were real people, which helped me come to see them that way, too. My sister, Laura, helped me with the music and other truths. My friends Barbara Abercrombie, Danny Brassell, Patti Goldenson, Denise Honaker, Lori Logan, Bridget O’Brian (who has been reading my work with keen insight for more than two decades!), Trisha Rappaport, and Susan Sawyer read and commented on various drafts. Faye Bender, my literary agent, guided me through a seamless genre switch and made an inspired match. Jackie Cantor, my editor, cried in all the right places (and in front of all the right people!), saw more in my work than I ever knew was there, and welcomed me into a hardworking team of professionals that included assistant Carolyn Morrisroe, cover designer Rita Frangie, copyeditor Denise Barricklow, and publicist Catherine Milne. Heartfelt thanks to you all!

W

EDNESDAY

EDNESDAY

There’s something oddly comforting about doctors’ waiting rooms. The art on the walls is always soothing, the receptionist at the desk is always cheerful, people’s voices are hushed and almost reverent, and the air is infused with the promising smell of soap, as if, behind the door, it’s not just people’s bodies that are being healed, but their lives that are being swept clean of anything that smacks of deficiency or decay. I couldn’t in a million years have become a doctor myself, since I lack two essential qualifications—namely a benign attitude toward blood and an ability to drum up compassion for strangers who, more often than not, bring their problems upon themselves. But in a strange way, my chosen field shares some of the same principles with the ancient art of healing. I’m a magazine writer, a freelancer—one of those people who brings you monthly promises of a thin waist, shining hair, fabulous shoes, an effortless vacation and a husband who happily does the dishes. I, too, operate on a faith that just about anything can be made better.

I shuffled through the magazines on the waiting room table and grabbed a two-year-old

Metropolitan Home.

I recognized it as an issue that contained an article I’d done on the merits of cork flooring, which, I had learned, is actually a renewable resource. It’s made from the bark of trees, so during harvest the trees aren’t damaged. As a floor, cork is warm and forgiving. It also has the unusual property of being mold resistant, which, in the foggy beach cities of Los Angeles, is a definite plus.

Metropolitan Home.

I recognized it as an issue that contained an article I’d done on the merits of cork flooring, which, I had learned, is actually a renewable resource. It’s made from the bark of trees, so during harvest the trees aren’t damaged. As a floor, cork is warm and forgiving. It also has the unusual property of being mold resistant, which, in the foggy beach cities of Los Angeles, is a definite plus.

I read the words I’d written with a cool satisfaction, then tossed

Metropolitan Home

back on the pile and picked up the new issue of

Town & Country.

A flock of subscription and perfume cards fluttered onto my lap. I picked them up and had just started scanning the table of contents when someone called my name.

Metropolitan Home

back on the pile and picked up the new issue of

Town & Country.

A flock of subscription and perfume cards fluttered onto my lap. I picked them up and had just started scanning the table of contents when someone called my name.

“April Newton?” a woman sang, with a slight rise at the end of my last name, as if questioning whether I was still there and had not, in fact, given up on getting my turn in the inner sanctum. I smiled to indicate that I was, indeed, April Newton. I stood and kept the magazine with me as I grabbed my purse and followed the woman down the hall.

I followed her past the large tropical fish tank and noticed that she was wearing soft pink scrubs that matched the soft pink walls. We walked down the hallway, which was hung with large black-and-white close-ups of roses and tulips, and into a dressing room with muted lighting. “Everything off but your panties,” the woman said. “Robe opens to the front. Put your clothes in one of the lockers and keep the key in your robe pocket.”

I fought the urge to interrogate this woman the way I might if I had been sent to interview her on a piece about the new customer-service features of breast care facilities around the country.

How many times,

I would ask,

do you estimate you’ve given those instructions? Do you ever just know, by their eyes or the way they hold their shoulders, that some women already know what to do? That they have, in fact, heard those instructions so many times that it sounds to them now like a poem or the lyrics to an old song? That they would rather dispense with the robe altogether, knowing that what they’ve come here to do is bare their bodies and their souls?

How many times,

I would ask,

do you estimate you’ve given those instructions? Do you ever just know, by their eyes or the way they hold their shoulders, that some women already know what to do? That they have, in fact, heard those instructions so many times that it sounds to them now like a poem or the lyrics to an old song? That they would rather dispense with the robe altogether, knowing that what they’ve come here to do is bare their bodies and their souls?

“Thank you,” I said, in response to her speech about clothing protocol.

I went to unzip my jeans and noticed that the zipper was already halfway down. This had been happening with some frequency lately and more than anything else, it surprised me. I had become thick around the middle. After so many years paying so much attention to my body—to how fit it was, how healthy, how resilient, how balanced—I had become thick around the middle without even realizing that it had happened. I took off my pants, pulled off my sweater, unhooked my bra— which had turned a kind of murky gray, speckled with little balls of pilled elastic—wrapped myself in a thick terry cloth robe and took the

Town & Country

into the inner waiting room.

Town & Country

into the inner waiting room.

It was a lounge like a spa. There was a pitcher of ice water and lemon on the side table, along with fresh brewed tea and a tray of shortbread cookies. Norah Jones was being piped in through speakers in the ceiling. I took a seat in a plush armchair. There was only one other woman in the waiting room with me, a woman about my age with hair even more red than mine and what appeared to be an immunity to the charms of women’s magazines. She sat in her own armchair on the other side of the low coffee table, with her arms crossed primly in her lap. My guess was that she’d never had a mammogram, and for a split second, I thought about breezily making such a guess. “First time?” I might say, as if coming to an appointment whose sole purpose was to determine whether or not you had cancer was something you could get used to.

I opened the

Town & Country

again. It was a magazine I’d never written for, which presented a kind of puzzle for me to solve. What was their style? How did they structure their pages? I turned to the wedding section and read the names of a couple who frolicked in the water off Martha’s Vineyard and another who posed on a wide swath of grass in Ireland, a long-haired setter sitting steadfastly by the groom. I flipped again to a section in the feature well that was entirely about sex.

Town & Country

sex.

Town & Country

again. It was a magazine I’d never written for, which presented a kind of puzzle for me to solve. What was their style? How did they structure their pages? I turned to the wedding section and read the names of a couple who frolicked in the water off Martha’s Vineyard and another who posed on a wide swath of grass in Ireland, a long-haired setter sitting steadfastly by the groom. I flipped again to a section in the feature well that was entirely about sex.

Town & Country

sex.

The main feature was a long his-and-hers article by a couple who had gone on a $6,000 sex therapy retreat at the Miraval Resort & Spa in Arizona. I immediately wondered how the piece had been assigned. How had the editors known that the writer and her spouse would be game for such an intimate outing? Or had the writers decided to go to the spa, then pitched the piece and gotten their weeklong romp in the desert covered as a business expense? I scanned the wife’s section. She quoted one of the sex therapists, who explained that their retreat was designed for couples who were in love, but who had, due to time and the pressures of modern life, lost intimacy. In his section, the man talked mostly about the concept of homework. Sex homework. And he was talking about how much fun it was to be told to do—or not to do—various things in bed with his wife. “For homework the first night,” he wrote, “we were told that if we had intercourse, we would get an F.”

For the past nine months, Rick and I had been sleeping in a small double bed in a rented efficiency apartment while workers tore the roof off our ranch house, ripped out the walls, leveled the beams, and then poured a foundation so they could build it all back again— bigger, better, more sleek and modern. Our fifteen-year-old daughter, Jackie, slept three feet from us on the other side of a paper-thin wall, and most nights she didn’t go to sleep until two or three hours after I did. I could count on one hand the number of times Rick and I had had sex in those nine months, and all of those times were soon after we moved. We had come to some sort of tacit agreement that our kisses would be chaste, our hands would not roam from the cool zones on our bodies and our eyes would not lock with meaning. It was amazing how much room there could be in a double bed. There was room to roll over, room to spread out, room enough to read and sleep and not once do anything that might be construed as an invitation to intimacy.

Other books

Nine Steps to Sara by Olsen, Lisa

Not All Who Wander are Lost by Shannon Cahill

The American Sign Language Phrase Book by Fant, Lou, Barbara Bernstein Fant, Betty Miller

Shanghai Shadows by Lois Ruby

Crystal Clear by Serena Zane

The Virgin's Pursuit by Joanne Rock

Tracking Magic: A Rylee Adamson Short Story by Shannon Mayer

Archangel's Storm by Nalini Singh

The Prodigies - La Noche de los Niños Prodigio by Bernard Lenteric

The Pen Friend by Ciaran Carson