The Language Instinct: How the Mind Creates Language (23 page)

Read The Language Instinct: How the Mind Creates Language Online

Authors: Steven Pinker

Subdue, subdid, subdone:

Nothing could have subdone him the way her violet eyes subdid him.Seesaw, sawsaw, seensaw:

While the children sawsaw, the old man thought of long ago when he had seensaw.Pay, pew, pain:

He had pain for not choosing a wife more carefully.Ensnare, ensnare, ensnorn:

In the 60’s and 70’s, Sominex ads ensnore many who had never been ensnorn by ads before.Commemoreat, commemorate, commemoreaten:

At the banquet to commemoreat Herbert Hoover, spirits were high, and by the end of the evening many other Republicans had been commemoreaten.

In Boston there is an old joke about a woman who landed at Logan Airport and asked the taxi driver, “Can you take me someplace where I can get scrod?” He replied, “Gee, that’s the first time I’ve heard it in the pluperfect subjunctive.”

Occasionally a playful or cool-sounding form will catch on and spread through the language community, as

catch-caught

did several hundred years ago on the analogy of

teach-taught

and as

sneak-snuck

is doing today on the analogy of

stick-stuck

. (I am told that

has tooken

is the preferred form among today’s mall rats.) This process can be seen clearly when we compare dialects, which retain the products of their own earlier fads. The curmudgeonly columist H. L. Mencken was also a respectable amateur linguist, and he documented many past-tense forms found in American regional dialects, like

heat-het

(similar to

bleed-bled

),

drag-drug

(

dig-dug

), and

help-holp

(

tell-told

). Dizzy Dean, the St. Louis Cardinals pitcher and CBS announcer, was notorious for saying “He slood into second base,” common in his native Arkansas. For four decades English teachers across the nation engaged in a letter-writing campaign to CBS demanding that he be removed, much to his delight. One of his replies, during the Great Depression, was “A lot of folks that ain’t sayin’ ‘ain’t’ ain’t eatin’.” Once he baited them with the following play-by-play:

The pitcher wound up and flang the ball at the batter. The batter swang and missed. The pitcher flang the ball again and this time the batter connected. He hit a high fly right to the center fielder. The center fielder was all set to catch the ball, but at the last minute his eyes were blound by the sun and he dropped it!

But successful adoptions of such creative extensions are rare; irregulars remain mostly as isolated oddballs.

Irregularity in grammar seems like the epitome of human eccentricity and quirkiness. Irregular forms are explicitly abolished in “rationally designed” languages like Esperanto, Orwell’s Newspeak, and Planetary League Auxiliary Speech in Robert Heinlein’s science fiction novel

Time for the Stars

. Perhaps in defiance of such regimentation, a woman in search of a nonconformist soul mate recently wrote this personal ad in the

New York Review of Books:

Are you an irregular verb

who believes nouns have more power than adjectives? Unpretentious, professional DWF, 5 yr. European resident, sometime violinist, slim, attractive, with married children…. Seeking sensitive, sanguine, youthful man, mid 50’s–60’s, health-conscious, intellectually adventurous, who values truth, loyalty, and openness.

A general statement of irregularity and the human condition comes from the novelist Marguerite Yourcenar: “Grammar, with its mixture of logical rule and arbitrary usage, proposes to a young mind a foretaste of what will be offered to him later on by law and ethics, those sciences of human conduct, and by all the systems wherein man has codified his instinctive experience.”

For all its symbolism about the freewheeling human spirit, though, irregularlity is tightly encapsulated in the word-building system; the system as a whole is quite cuspy. Irregular forms are roots, which are found inside stems, which are found inside words, some of which can be formed by regular inflection. This layering not only predicts many of the possible and impossible words of English (for example, why

Danvinicmism

sounds better than

Darwinismian

); it provides a neat explanation for many trivia questions about seemingly illogical usage, such as: Why in baseball is a batter said to have

flied out

—why has no mere mortal ever

flown out

to center field? Why is the hockey team in Toronto called the

Maple Leafs

and not the

Maple Leaves?

Why do many people say

Walkmans

, rather than

Walkmen

, as the plural of

Walkman?

Why would it sound odd for someone to say that all of his daughter’s friends are

low-lives?

Consult any style manual or how-to book on grammar, and it will give one or two explanations as to why the irregular is tossed aside—both wrong. One is that the books are closed on irregular words in English; any new form added to the language must be regular. Not true: if I coin new words like

to re-sing

or

to out-sing

, their pasts are

re-sang

and

out-sang

, not

re-singed

and

out-singed

. Similarly, I recently read that there are peasants who run around with small tanks in China’s oil fields, scavenging oil from unguarded wells; the article calls them

oil-mice

, not

oil-mouses

. The second explanation is that when a word acquires a new, nonliteral sense, like baseball’s

fly out

, that sense requires a regular form. The oil-mice clearly falsify that explanation, as do the many other metaphors based on irregular nouns, which steadfastly keep their irregularity:

sawteeth

(not

sawtooths

),

Freud’s intellectual children

(not

childs

),

snowmen

(not

snowmans

), and so on. Likewise, when the verb

to blow

developed slang meanings like

to blow him away

(assassinate) and

to blow it off

(dismiss casually), the past-tense forms remained irregular:

blew him away

and

blew off the exam

, not

blowed him away

and

blowed off the exam

.

The real rationale for

flied out

and

Walkmans

comes from the algorithm for interpreting the meanings of complex words from the meanings of the simple words they are built out of. Recall that when a big word is built out of smaller words, the big word gets all its properties from one special word sitting inside it at the extreme right: the head. The head of the verb

to overshoot

is the verb

to shoot

, so

overshooting

is a kind of

shooting

, and it is a verb, because

shoot

is a verb. Similarly, a

workman

is a singular noun, because

man

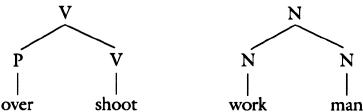

, its head, is a singular noun, and it refers to a kind of man, not a kind of work. Here is what the word structures look like:

Crucially, the percolation conduit from the head to the top node applies to

all

the information stored with the head word: not just its nounhood or verbhood, and not just its meaning, but any irregular form that is stored with it, too. For example, part of the mental dictionary entry for

shoot

would say “I have my own irregular past-tense form,

shot

.” This bit of information percolates up and applies to the complex word, just like any other piece of information. The past tense

of overshoot

is thus

overshot

(not

overshooted

). Likewise, the word

man

bears the tag “My plural is

men

.” Since

man

is the head of

workman

, the tag percolates up to the N symbol standing for

workman

, and so the plural of

workman

is

workmen

. This is also why we get

out-sang, oil-mice, sawteeth

, and

blew him away

.

Now we can answer the trivia questions. The source of quirkiness in words like

fly out

and

Walkmans

is their

headlessness

. A headless word is an exceptional item that, for one reason or another, differs in some property from its rightmost element, the one it would be based on if it were like ordinary words. A simple example of a headless word is a

low-life

—not a kind of life at all but a kind of person, namely one who leads a low life. In the word

low-life

, then, the normal percolation pipeline must be blocked. Now, a pipeline inside a word cannot be blocked for just one kind of information; if it is blocked for one thing, nothing passes through. If

low-life

does not get its meaning from

life

, it cannot get its plural from

life

either. The irregular form associated with

life

, namely

lives

, is trapped in the dictionary, with no way to bubble up to the whole word

low-life

. The all-purpose regular rule, “Add the

-s

suffix,” steps in by default, and we get

low-lifes

. By similar unconscious reasoning, speakers arrive at

saber-tooths

(a kind of tiger, not a kind of tooth),

tenderfoots

(novice cub scouts, who are not a kind of foot but a kind of youngster that has tender feet),

flatfoots

(also not a kind of foot but a slang term for policemen), and

still lifes

(not a kind of life but a kind of painting).

Since the Sony Walkman was introduced, no one has been sure whether two of them should be

Walkmen

or

Walkmans

. (The nonsexist alternative

Walkperson

would leave us on the hook, because we would be faced with a choice between

Walkpersons

and

Walkpeople

.) The temptation to say

Walkmans

comes from the word’s being headless: a Walkman is not a kind of man, so it must not be getting its meaning from the word

man

inside it, and by the logic of headlessness it shouldn’t receive a plural form from

man

, either. But it is hard to be comfortable with any kind of plural, because the relation between

Walkman

and

man

feels utterly obscure. It feels obscure because the word was not put together by any recognizable scheme. It is an example of the pseudo-English that is popular in Japan in signs and product names. (For example, one popular soft drink is called Sweat, and T-shirts have enigmatic inscriptions like

CIRCUIT BEAVER, NURSE MENTALITY

, and

BONERACTIVE WEAR

.) The Sony Corporation has an official answer to the question of how to refer to more than one Walkman. Fearing that their trademark, if converted to a noun, may become as generic as

aspirin

or

kleenex

, they sidestep the grammatical issues by insisting upon

Walkman Personal Stereos

.

What about flying out? To the baseball cognoscenti, it is not directly based on the familiar verb

to fly

(“to proceed through the air”) but on the noun

a fly

(“a ball hit on a conspicuously parabolic trajectory”). To

fly out

means “to make an out by hitting a fly that gets caught.” The noun

a fly

, of course, itself came from the verb

to fly

. The word-within-a-word-within-a-word structure can be seen in this bamboo-like tree: