The Knight in History (21 page)

Read The Knight in History Online

Authors: Frances Gies

The afternoon services of nones and vespers were said at two or three and five or six. The only brothers excused were “the brother of the bakery, if he had his hands in the dough, and the brother of the great forge, if he had boiling iron on the fire…and the brother of the smithy if he was shoeing a horse…or a brother who was washing his hair,” and these must come to say their prayers when they were able.

21

After vespers, supper was served, with the same ceremony as dinner. During fast days only one meal was eaten, but one adequate for fighting men who needed to stay in top condition. The celebrated Paris preacher Jacques de Vitry, who became bishop of Acre in 1216, preached a sermon to the Templars in which he told a story to emphasize this point:

“Once there were certain brother-knights of your House who were so fervent in fasts and austerities that they easily succumbed to the Saracens through the weakness of their bodies. I heard about one of them, a very pious knight, but without prowess, who fell from his horse at the first lance blow that he received in a skirmish with the infidels. One of his brothers helped him back into the saddle, with great danger to his own person, and our knight rode again toward the Saracens, who unhorsed him again. The other knight, having twice raised and saved him, said, ‘Look out for yourself henceforth, Sir Bread-and-Water, for if you are knocked off again, I won’t be the one to pick you up!’ ”

22

At nine, when compline was rung, the brothers assembled to drink diluted wine and receive their orders for the following day. Each then tended again to his horses and harness, “and if he has anything to say to his squire, he must say it pleasantly and softly, and then he may go to bed. And when he is in bed, he must say an Our Father so that if he has committed any sin since compline God may pardon him. And each brother must keep silence from compline to prime, except for a necessity.”

23

Silence was maintained at night even when on the march.

24

To sustain discipline, the severest penalties were dismissal, temporary exile from the Order, or temporary loss of the habit. Many of the prohibitions were concerned with ordinary crimes or misdemeanors: simony, in this case giving or accepting a bribe to secure admission to the Order; killing or injuring Christians; theft, embezzlement; carnal intercourse with a woman; sodomy; false witness; unbelief; refusing hospitality to a traveling brother; giving away or wasting the Order’s property. Brothers could not possess money of their own, or carry it without permission. Fighting among the brothers was condemned—they must not “maliciously thrust at or strike a brother…and if shedding of blood should result, they may be imprisoned.”

25

Strict obedience was stressed above all. The brothers could do nothing without permission—“bathe, or be bled, or take medicine, or go to town, or gallop a horse.”

26

In battle they were not to attack without the leader’s command “except that they should do this to help any Christian being pursued by a Turk intending to kill him.” During a

chevauchée

, they must maintain their line of march, although a knight could take a quick turn to try his horse and harness. In combat, disobedience was severely punished. A knight who separated himself from his squadron was sent back to camp in disgrace, on foot, to stand trial by “the justice of the House.”

27

Even the Commander of Acre, Brother Jacques de Ravane, was put in irons for making an unauthorized raid that ended in disaster.

28

Likewise, Brother Baldwin de Borrages, commander at Chateau Pélérin, escaped judgment of the Order after a similar incident only by fleeing the country.

29

The worst conceivable crime for a member of a Military Order was apostasy, denying the Cross, even to save his life. Roger l’Aleman, a Templar knight with powerful connections, was expelled from the Order for reciting from the Koran while a prisoner, despite his protest that he had been tricked.

30

In the Crusade of St. Louis (Louis IX of France), the last full-scale Crusade of the Middle Ages (1249–1252), the Military Orders can be seen in all their typical roles: as soldiers, diplomats, and bankers.

Both the Templars and the Hospitalers took part in the decision-making that preceded the Crusade. The Orders were represented at the council of war that chose Egypt as the target of attack. They did not, however, agree with the decision. The Master of the Temple, Guillaume de Sonnac, and the Marshal of the Hospitalers, Guillaume de Corceles, both wrote Louis warning him that Egypt and Damascus, traditional rivals, were negotiating an alliance that would upset the balance of power and threaten the weak Christian coastal settlements of Jaffa and Caesarea. De Sonnac reported that he had been approached by an Egyptian emir who wanted a treaty with the Crusaders and offered to put the king in touch with him. It was rumored among the Crusaders that De Sonnac had himself initiated the détente—in the picturesque expression of a chronicler, that he and the sultan had “concluded such a fine peace that they had had themselves bled in the same basin.”

31

Louis wrote the Master forbidding such unauthorized relations with the enemy.

32

A Templar officer, Renaud de Vichiers, former Master of the Temple in France, now serving as Marshal in the Holy Land, accompanied the king on his journey to the East. The Templar contingent was led by Guillaume de Sonnac. The current Master of the Hospitalers, captured at the battle of Gaza five years before, was still a prisoner in Cairo, and the Marshal of the Hospital commanded in his place.

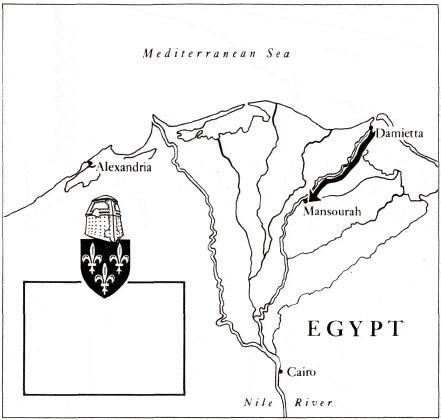

EGYPT-THE CRUSADE OF ST. LOUIS

Contrasted with the troops of the French king, who were arrayed in the usual motley variety of garments and armor, the Orders presented the uniform appearance of a modern army. Each Templar knight wore over his mail hood a rigid helmet that left only the face uncovered, and over his hauberk his white coat of arms sewn back and front with red crosses. Templar sergeants wore black tunics, also adorned with crosses.

33

The Hospitalers, who had previously worn black monastic robes over their armor, had recently adopted tunics with crosses similar to those of the Templars (which a decade later they changed for scarlet tunics with white crosses).

34

Besides the brother knights and sergeants of the Orders, both Templars and Hospitalers employed troops from outside their membership, lay knights who were their vassals, mercenary knights, and Turcopoles.

The two Orders had recently been involved on opposite sides of one of the intermittent civil wars of the Latin states, but in preparation for his expedition St. Louis had taken care to get them reconciled. The Crusade began well, with a successful landing on June 4, 1249, at the mouth of the Nile across from Damietta. After several hours’ assault, Damietta was evacuated by the Muslims, and the Crusaders streamed into the city. The leaders of the army were billeted in mosques and palaces, while the Templars, Hospitalers, and other troops pitched their tents on the island in the Nile where they had disembarked. The Templars placed the tent that served as chapel in the middle of their camp, the round tent of the Master next to it, then the tents of the Marshal and Commander and of the commissariat, the tents of the knights in a circle around the chapel. When firewood and fodder for the horses had been brought by the squires, food was distributed and the knights ate in their tents.

35

The promising beginning was not followed up. One of the king’s brothers, Alphonse of Poitiers, was late in arriving with his command, and it was not until five months later, in November, that the advance toward Cairo began.

In the march the Military Orders took the key positions of van-and rearguards. The knights rode in squadrons, their squires either in front, carrying their lances, or behind with their relief mounts. They never broke ranks on the march.

36

The king wished some of their discipline would rub off on his own men, one of whom, Gautier d’Autreche, during the fighting at Damietta had been mortally wounded in a single-handed foray, causing Louis to comment that “he would not care to have a thousand [such] men.”

37

The submarshal of the Templars rode at the Marshal’s side carrying the banner. To give the signal for a charge, the Marshal took the banner, while other knights grouped themselves around him to protect it; if the Marshal was killed, a knight named by him in advance replaced him. It was strictly forbidden to lower the banner or to use it as a lance.

38

South of Damietta the army halted and dammed a small tributary of the Nile to make a ford. As the Templar van started to cross, according to the eyewitness account of St. Louis’s biographer and seneschal, Jean de Joinville, the Muslims suddenly attacked. At first the Templars held formation and refused to risk counterattack, but when a Turk brought a Templar to the ground directly in front of the Marshal, he exclaimed, “For God’s sake, let’s get at them! I can’t stand it any longer!” and struck his spurs into his horse. The whole army followed the Templars and all the Turks, according to Joinville, were killed.

39

When the French approached the main Egyptian defensive position at Mansourah, separated from them by a branch of the Nile, they came under severe fire of enemy missiles. The king ordered a causeway constructed across the river. Covered walkways (cats) were built to shelter the workers from stones hurled by Egyptian siege machines on the other side. Work on the causeway began a week before Christmas, but it was constantly frustrated by the Saracens, who dug new channels for the stream on their bank.

On Christmas day as Jean de Joinville and his knights sat at dinner in the tent of another French lord, the Saracens attacked and killed some knights strolling outside the camp. Joinville and his host hastily armed themselves and galloped out to fight, but would have been overpowered by numbers had not “the Templars, who on hearing the alarm had come up, covered our retreat well and valiantly.”

40

The Saracens began to hurl missiles of Greek fire, setting the movable towers and catwalks ablaze. The situation seemed hopeless, when a native offered to sell crucial information: the location of a ford farther down the river. The crossing was planned for February 7. An advance guard composed of the king’s brother Robert of Artois, the Templars, and an English contingent was to ford the river, secure the opposite bank, and wait for the others to cross; again the Templars were to form the vanguard, the count of Artois was to lead the second rank, and the king would follow with the rest of the army.

The crossing was achieved—with some difficulty, for the water was deeper and swifter than the native had said. Once across, Artois and his men ignored their orders and set off in impetuous pursuit of the enemy. Brother Gilles, the Commander of the Temple, admonished the count to stop and wait for the king and the rest of the army, appealing to his pride as a knight by assuring him that in making the crossing he had already accomplished “one of the greatest knightly deeds that had been done in a long time in the East.” If they allowed themselves to be scattered and divided, the Saracens would rally and overpower them. One of the count’s knights accused the Templars of being wolves in sheep’s clothing: “If the Templars and the Hospitalers and the others in this country wanted it so, the land would have been conquered long ago!” The count told Brother Gilles to stay if he was afraid. Gilles replied, “Sire, neither I nor my brothers are afraid…. We will go with you, but truly we doubt if either we or you will return.”

41

The rash count and his men pressed on toward Mansourah, while the Templars, unable to dissuade, loyally supported. The army “struck spurs into their horses and rushed headlong in pursuit of the Turks, who fled before them, right through the town of Mansourah and on into the fields beyond towards Cairo.” There they came face to face with a fresh enemy force, the Mameluk guard of the emir Baybars. Retreating into the narrow streets of the town, the French found themselves in a trap, as the enemy threw down from the rooftops “great beams and blocks of wood.” The count of Artois was killed “and so many other knights that the number of dead was estimated at three hundred,” wrote Joinville. “The Templars, as their Master told me later, lost on this occasion some two hundred and eighty men-at-arms.” The Master himself, wounded in the face, lost an eye.

42