The Kitchen Readings (20 page)

Read The Kitchen Readings Online

Authors: Michael Cleverly

Wednesday, February 16, 2005

It was a February Wednesday. Aspen was at 90 percent occupancy, good for the mercantile interests, waitresses and waiters, ski instructors, and everyone in the trickle-down cascade of resort economies.

“Marky Mark” and “Big Wave Dave,” two surfers from Santa Barbara, were in Aspen for a few days of skiing. They were staying at the St. Regis, one of Aspen's premier hotels, located at the base of the mountain. Mark, with a day job in commercial real estate, had helped DeDe, my sweetheart, to invest in a former aircraft assembly plant out on the coast. DeDe was happy when she flipped the property at a large profit. Their friendship had endured. He invited us for dinner at a hip new bistro in an old

building on Hopkins Street. The food was good, and every seat was filled. Midway through our main course, “Big Wave” said that he and Mark had read everything that Hunter Thompson had written, admired him greatly, and asked if it might be possible to meet him during their short stay. I said that I'd call him after dinner.

Over the years I had fielded hundreds of requests to introduce people to Hunter. The Doc's phone numbers were not published, but mine were. It was common knowledge that Hunter and I were friends, and pilgrims from all over the world thirsted for a one-on-one audience with him. Some fans had even called me at 911. I vetted most of these requests by getting some details and a callback number, but I rarely bothered Hunter with this litany of suitors. I even treated friends' requests to hang out with Hunter as a general annoyance and imposition on him and rarely showed up with company. If I asked him if it was okay to bring somebody he would rarely decline, and I avoided abusing his hospitality.

Still, I liked my new friends and told them that if Hunter was up and about, not jamming on a deadline, a postprandial drive to Woody Creek might be in the cards. Just before dessert was delivered, my cell phone lit up. “Hi, it's Bob,” I answered. “Bob, Hunter. What are you doing?” “Well, Hunter, I'm in town at dinner with DeDe and two dudes from California who are huge fans of yours.” “Well, think they would like to come over?” “Yeah, I do. See you in half an hour.”

We left the bistro. Mark and Big Wave picked up a bottle of ancient single malt that I would have had to take out a loan to pay for, and we headed to Woody Creek by the back road. I told our friends that I could not predict what kind of experience we were in for. DeDe knew why I was delivering this disclaimer.

Hunter could be warm and affable, rattlesnake mean, or unconscious. Buy the ticketâ¦

We filed into the kitchen. Hunter was perched and fully dressedâa good sign. Introductions were made. Hunter hugged me and then hugged DeDe, while grabbing her ass. Normal welcome.

The next three hours were animated and fun to watch. Dave and Mark were extroverts. They submitted to Hunter's journalist interrogation and proved their knowledge of politics and sports. They felt comfortable in the strange world of Owl Farm. Hunter asked them if they would read from his works. On the kitchen counter were five or six of his books, each earmarked with sticky notes, and Hunter picked one up, opened it to a certain passage, and handed it to Dave. Dave began reading.

Hunter loved to hear his writings read aloud. During these readings he would look into the void, as if he were at a symphony or a jazz concert, and he would rock to the cadence of his words. He had hand signals that told the reader to slow down, read louder, read faster, or whatever Hunter thought would benefit his words. He was a conductor. If a reader mispronounced a word or left out a wordâa word perhaps written twenty-five or thirty years earlierâHunter would look up and ask, “Are you sure that's what I wrote?” Hunter knew. Like a mathematician with his unique formulae, Hunter

was

his writing. I had ceased being amazed years before, but Mark and Dave were impressed.

In the ensuing hours, Hunter was on his game. We were all laughing, and the room was saturated with mutual respect and an apparent joy for life. I had been aware of stress in Hunter's life. His business and his relationship and his health were all bothering him. Over the previous weeks, I'd answered his summonses many times. We had discussed possible solutions to vari

ous problems as he identified them. During these days we were always alone and often sat in the living room by the fire. One-on-one dialogues with Hunter were rare, precious, and revealing. With me, Hunter shed most of his paranoia and privacy. I would digest what he said and offer my thoughts and experiences without reservation. These exchanges were intimate, adult, and emotional. Over the years, we had shared such moments, and they had drawn us closer. I felt that I was able to assess Hunter's moods. On this Wednesday night, I thought Hunter's mood seemed perfect.

At about one in the morning, I said that I had to go to work early on Thursday. Dave and Mark wanted to ski but would probably have spent all night reading and talking. We said good night and got in my car. On the way into town we all felt that we had experienced a night of vintage Hunter. It was a small group with good chemistry, and now each of us is forever bound to the others by the fact that it was the last time any of us saw HST alive. On Sunday, Hunter took his life. Mark and Dave have a story to tell. Hunter loved stories. Long after that final, fatal Sunday, I still reflect on that Wednesday evening and wonder if it was a gift from Hunter, or a last gift from Hunter.

Friday, February 18, 2005

The week before Hunter died, our old friend Loren Jenkins was in town. That Wednesday, Loren and I met with Hunter at Owl Farm. We had a terrific afternoon; we solved many of the problems of the world and conspired to create new ones. When Loren and I hooked up the next day we agreed that it had been a fine time. Hunter at his best. I would have remembered that afternoon fondly, no matter how much longer Hunter had lived.

I was over at Hunter's again two days later. He was in excellent spirits. It was just the two of us. Anita had gone to the movies with her friend Sue. We talked about John Belushi. I had brought him up for some reason. His brother-in-law, Rob Jacklen, had lived in Aspen in the wild old days and we had both known him.

Hunter, of course, was close to John. We watched a basketball game. It was a rerun, but I didn't know that. Hunter had watched it a couple of evenings before. He made me gambleâgame bet, proposition bets, the works. I wasn't doing very well. I wasn't suspicious; he'd usually win even when he wasn't bothering to flimflam me. Basketball is not my game.

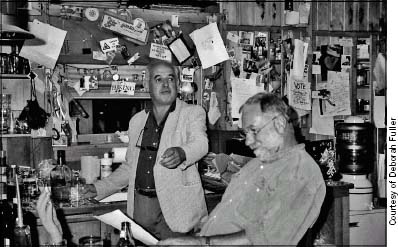

The great Ralph Steadman and Cleverly; a classic kitchen evening.

Hunter had a lot of irons in the fire. The high-end art publisher Taschen was releasing a new edition of

The Curse of Lono,

first published in 1983. Ralph Steadman had done spectacular color illustrations for it, but the original edition hadn't come close to doing them justice. Hunter and Ralph had always felt slightly betrayed by this, so the new edition was a big deal. Hunter himself was working on an article for

Playboy

on Sean Penn's remake of the film

All the King's Men.

Penn and Hunter were good friends, and Doc had recently returned from New Orleans where the film was shooting. Hunter and I were schem

ing up a sequel to my 2002

Sex and Death

calendar. Hunter was sure that Taschen would want to be involved in a project of such profound artistic merit. We were obliged to study dirty pictures as research. Hunter had other stuff in the works, too.

Physically, Hunter felt pretty crappy. He was coming back from a series of medical problems, and it was a very slow, painful process. I honestly thought that he was improving. You could tell by the griping that he was making an effort. Physical therapists were coming and going from Owl Farm regularly; sometimes debauchery and sin had to be put off. That evening Doc really seemed to feel okay.

So that last night was business as usual to me. We drank a bit, did a little of this, a little of that. At the end of the game, Hunter came clean about it being a rerun. He pointed at the screen. “See that tiny logo up in the corner?” I made my way over to the TV and put my nose up to the screen. It read, “Instant Classics.” “What does it mean?” I asked. “It means I watched this game two nights ago.” He forgave my debts and my stupidity. Who knows if he'd conned me before and not 'fessed up? If he had, his admission that night might have been telling. We'll never know.

Anita and Sue got home some time after eleven. They were bubbly and chatty; it had been a good movie. Eleven can be getting late for me, but it was always considered early at Owl Farm. I would leave soon.

A couple of days after Hunter's death I was quoted in a news story as saying that I would have been less surprised if he'd shot me. That was true. I had no idea. Woody Creek has never been considered an epicenter of mental health. It took a personality as large as Hunter's to actually stand out. There were always plenty of nutcases running around the neighborhood, but Hunter was never one of them. If I had been told that someone was going to

do himself in, I could have made a list, but Hunter would have been at the bottom.

Not every evening at Owl Farm was a party. In recent years the kind of behavior that Hunter's young fans found so appealing was less and less frequent. An average night would more likely have been Hunter and a close friend or two discussing politics or some other current event. Serious and sober middle-aged guys doing what middle-aged guys do. This would on occasion be a disappointment to some fan who had gained admission, expecting to see a Bill Murray or Johnny Depp version.

Hunter worked. He had been producing a weekly column for ESPN for some time. He always had a book deal going, usually involving more than one expected volume. Then there were magazine pieces. It's pretty hard to keep a lot of balls in the air if your hands are full of something else.

People are still reading Hunter, as they have been for decades. I don't know if his books have ever gone out of print. One reason people read him is because he was very funny. He was very funny because he was very smart and because he was very honest. Hunter was a sixty-eight-year-old man who spoke to young people. He was a boozer and druggie who spoke to people who never embraced booze or drugs themselves. And he was a liberal who spoke to people whose political leanings were far away from his own. We all recognized that there was something in Hunter that we could only hope to see in ourselves: an utter lack of hypocrisy. When Hunter was being brutally honest with those around him it could sometimes be unpleasant, but he was just as honest about himself. He didn't sugarcoat it. In that sense he didn't play favorites.

I announced that I was leaving. “What do you mean you're leaving?” “It's late, Doc. I've had enough; the girls are back.

They can minister.” He wasn't happy. The idea of being outnumbered by two effervescent females clearly didn't appeal. Anita and Sue came back into the kitchen, we made some small talk, and they wandered into the living room. “Okay, Doc. I'm outta here.” I hollered goodnight to the gals. Hunter, giving me the stink-eye. “Fuckyoufuckyoufuckyoufuckyou.” I walked through the Red Room smiling and waving goodnight. “Fuckyoufuckyoufuckyou⦔

The next day I saw Sue. “How much longer did you stay?” I asked. “Only about ten minutes. We read for a bit then he called me a fucking bitch and told me to get the hell out.” We laughed. No offense meant, no offense taken. The perfect end to a delightful night at Owl Farm.

By the following evening our friend was gone.

A February Sunday evening. Me, the cats, and the woodstove, not much happening, perfect. There's a knock on the door. My friend and neighbor Joe Fredricks is standing there, and I let him in.

Joe plows my driveway. I give him a piece of art, and he plows all winter. He'd gladly do it for nothing, but I'm flattered that he likes my stuff, so I don't mind coughing up. He plows Hunter's, too, and in the summer takes care of any heavy equipment at Owl Farm. Joe is also a Hunter buddy and attends all the major events.

This Sunday night drop-in is unusual. Joe is a volunteer fireman and has a scanner in his truck. A gunshot has been reported

at an address on Woody Creek Road. We don't recognize the street number and try to figure out whose place it might be. That a gunshot in this neighborhood should be reported at all is a bit strange; it's Woody Creek, after all. We figure out nothing, and Joe decides to cruise down toward Hunter's and report back. I wait with limited interest.

Minutes later the phone rings. It's the sheriff. He's at Owl Farm. He gives me the news. Joe returns, and I tell him that I've heard. We have a couple of shots of tequila. The dispatcher on the scanner had the address wrong.

I didn't go out for the next few days. I didn't want to be underfoot at Owl Farm. But when I finally left the house, that's where I went. Hunter's family and his closest friends did the same, hunkered down. There were people less close to Hunter who hung at the Tavern holding court and giving interviews.

Some of us gave phone interviewsâthe press was going to talk to someone; better, we thought, people who really cared for Hunter than some rummy at the bar. All the time between Hunter's death and when I finally went over to Owl Farm I very much wanted to be there, to see Anita, Juan, and Jennifer. As soon as I got there, all I wanted to do was leave. I'm not exactly sure why; maybe because being in the house made it official. I'd never be in the kitchen with Hunter and our friends again.

So my visit that evening was brief. The next day I finally had to go out for provisions. The

Aspen Daily News

was sitting on the counter at the liquor store with a full-page picture of Doc. Seeing it did something to my chest I'd never felt before. When I got home there were sixty new messages on my machine.

During the next few days, patterns began to emerge. I'd stop by Hunter's intermittently; friends would drop off food there, the frenzy at the Tavern settled down, and the phone stuff tapered

off. There was security all over Owl Farm. Guys taking themselves really seriously, which was their job, I guess. I wondered what Hunter would have thought.

From the evening of his death, those closest to Hunter wanted to get together for something small and informal. My favorite idea was to gather at Bob Rafelson's house and order a bunch of pizza. That had legs for a couple of days, but as time passed things inevitably got bigger, until at one point there was the thought of having a “come one, come all” at an Aspen nightclub. Bob Braudis felt that was a spectacularly bad idea and a recipe for chaos on a biblical scale. Bob Rafelson's voice got low and serious. “I've seen these things,” he said. “There'll be helicopters; there'll be no way to control it.” The man charged with public safety emerged. Sheriff Braudis suggested that people clear their heads and try again.

A couple of days later I was alone in the kitchen with Juan and he gave me a handwritten list. He said there was going to be a very private memorial at the Hotel Jerome a couple of weeks hence. He explained that the guest list didn't include everyone Hunter had ever known or worked with, just the friends he saw and called regularly, and with that in mind, he wanted my opinion. The list was several pages long. Hunter liked to call a lot of people. I added a few names, people I knew had either canceled trips or were flying in, to be here for whatever sort of memorial did happen. I also mentioned that I thought I owed it to Hunter to personally bring as many beautiful women as I could round up. Juan concurred.

The gals I usually hang out with were all on Juan's list anyway, so I was free to bring any date(s) I wanted. Despite my glib comment to Juan about herds of beautiful women, I really wasn't in the mood for that kind of hunt. I ended up taking Kallen, one

of the great beauties from the golden age of the Jerome, an old friend whom I now saw rarely, a good example of the people who had been close to Hunter in the seventies and eighties but who had fallen away in recent years. She wasn't on the list. Anita had never met Kallen but knew of her from a famous photograph of Hunter, Kallen, and other luminaries taken at Doc's end of the bar at the Jerome back when that was the place to be. Anita was glad that she was going to get to meet Kallen at last.

I stopped by Kallen's place of work to discuss some details. We figured stuff out, and then she went on to tell me that she had channeled Hunter the evening before. “I beg your pardon? Channeled?” She told me how she and a friend had hooked up with Doc in the hereafter and proceeded to relate the conversation and revealed new and interesting facts. Naturally, I was pretty excited that my date had spoken to my dead friend. This was an unforeseen development. I gave Kallen a peck goodbye, and for the next few days imagined a number of scenarios in which Kallen broke the “channeling” news to Anita during the memorial, with tears, anguish, and general hysteria ensuing. I was not looking forward to witnessing any of those scenes being played out.

The event was nearing, and I was sitting with Anita trying to figure out how to tell her about this “chatting with the deceased” situation. I wasn't having much luck. Finally I just started in. “Listen Anita, I have to tell you something.” I proceeded, with much trepidation, to lay out the channeling thing as I understood it. When I finished, I looked at Anita and this huge smile was spread across her face; she was beaming. “Me, too. I channeled Hunter just last night!” she gushed. I realized I had nothing to worry about. Clearly she and Kallen would get along just fine.

The memorial at the Jerome looked as much like a Hollywood red carpet event as a gathering for a man of letters; the celebrity count was over the top. In addition there was plenty of local security plus Secret Service guys with wires in their ears, all there to prevent anything unpleasant from happening to the big-name politicians. It was a mixed crowd.

There was an open bar, of course, and a beautiful buffet in the middle of the ballroom. I'd never seen so many intelligent, successful, talented people so wasted. These truly were Hunter's friends. As an Oscar-winning actor was passing through the buffet, he noticed a pair of feet sticking out from under the tablecloth. He grabbed the ankles and dragged out a local reporter, obviously a Thompson buddy. The reporter didn't come to until the next morning. He was disconsolate for days at having missed so much of an excellent party. Laila Nabulsi, a Hollywood power player, producer of

Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas,

and one of the best women in the world, introduced me to a handsome actor. We found some chairs and sat down and talked and drank. Purely by coincidence, every woman in the building who had previously met me for at least five seconds came over to say hello and see how I was doing. It was lucky timing; they also got to meet the actor. Yeah, he had an Oscar, too.

There were speeches, lots of speeches. Historian and author Doug Brinkley was the de facto MC and kept things moving along. There'd be a break after every two or three speeches so people could hit the buffet, bar, head, whatever. There were touching speeches; there were funny speeches; and that evening, some of the most articulate people I knew were so fucked up they could barely work their lips. The speeches were a mixed bag.

The event was scheduled to end at ten or eleven, and there were two or three after parties scheduled. One person had rented

out an entire restaurant, one of the “inner circle” was having people down to his house, and there was something else at a local night spot. Two of them never happened. The Jerome was so good no one left. It was still going when I lurched off at 2:00

A.M

. People did eventually head down to the friend's house and party till dawn, but without me. I dropped Kallen off and considered myself extremely lucky to make it home. I was almost in the sack when the phone rang. It was a beautiful woman I had met during the course of the evening, asking me where the party was. Every man on planet Earth knows there's only one answer to that question. But Genius gave her directions to the party.

Â

When Johnny Depp arrived in Aspen for the Jerome memorial he was carrying something large. When Sheriff Braudis saw it he commented, “That must be interesting to travel with.” Depp replied, “Hunter was interesting to travel with.”

Almost from the beginning there had been scuttlebutt about a blastoff. There was talk of using one of the cannons from the ship in

Pirates of the Caribbean,

and the

Aspen Daily News

actually sponsored a contest for people who owned cannons. They were to send in a videotape of their cannon and explain why theirs should be the one to send Hunter off. There was also a rumor that something was already being fabricated in L.A. All this was engendered by a scene in a BBC documentary in which Hunter talked about, and even described, a cannon that would shoot his ashes into space. The scene was included in the boxed set of

Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas

and was also in Wayne Ewing's documentary

When I Die.

In the end, there was no need for the contest. Depp had been carrying an architectural model; behind it was a curved diorama almost four feet high and about as wide. The model was of a tall stainless-steel column, the top

of which turned into a dagger and a giant gonzo fist. It sat on a contoured topography of rolling fields with little scale-model people; in the background on the diorama were mountains and sky. The people were tiny, to scale; the actual thing would have been enormous. The scale-model people were gazing up in awe at the fist, and some were taking pictures. There was an actual presentation that went along with the model. It plugged in and you turned it on. There was a large piece of silk that shrouded the entire column. The music started and as someone slowly pulled the silk off the fist, the music changed and suddenly the peyote button lit up and began to change colors. The music changed, the colors changed and whirled; it was all very theatrical, very impressive. Word on the street, Woody Creek Road, was that Johnny Depp had pledged four million dollars to the project. None of us had ever been to a four-million-dollar party.

In fact, the monument was to be 153 feet high, a little taller than the Statue of Liberty. One person noted that there probably weren't any buildings that tall between Denver and Salt Lake City. When the “fist” went from rumor to reality, there were lots of questions. Was this thing to be permanent? If so, did rural Woody Creek want to live with such a thing? If so, how did Pitkin County, the most regulated county on the planet, feel about it? Was it so tall as to pose a danger to aircraft? There were meetings, lots of meetings. What about the blastoff itself? One of the most prestigious fireworks companies in the country was contracted, people who do things at the Washington Monument. Colorado had been in a drought for years. Wildfires were springing up all over the Southwest every summer, and every summer it was touch and go whether the sheriff could allow the Fourth of July fireworks display on Aspen Mountain. What about burning down Woody Creek?

It was spring when these questions arose and Johnny Depp's front man arrived in town. The event planner, a relentlessly officious twit, showed up at his first meeting with county officials wearing an Armani suit. This didn't impress the guys in jeans and cowboy boots. You don't get to be an upper-level Hollywood suck-up by being totally unconscious, so he got with the dress code pretty quick. His Armani attitude remained, though. News of the blastoff spread and was picked up by the media. To say that the guest list was exclusive, a hard ticket, was something of an understatement. What of Hunter's legions of fans? The more ardent of them had had no respect for Hunter's privacy when he was alive and dangerous; there was no reason to expect any from them now. Anxiety was abroad in the land.

The event planner thought a Jumbotron, the kind of huge screen you see in football stadiums, could be set on the mesa across Woody Creek from Owl Farm. They'd just build a road where there had been none, erect a huge screen, truck in lots of porta-pottiesâ¦you get the idea. Important people on one side of Woody Creek at the event, the unwashed masses on the other side. He approached a member of the Craig family, who owned that property. His pitch was pretty poor. He tried to wow them with dollar signs and celebrity name-dropping. Gee! They'd even get a whole free road out of it. The Craigs had a good deal of affection for Hunter, and probably would done what they could purely out of that affection, but they couldn't have cared less about Hollywood celebrities and Hollywood money. They had no need for a free road to nowhere.

The Jumbotron idea then migrated to Buttermilk Mountain. This was a little more realistic. The base of Buttermilk had been used for Jazz Aspen concerts and had seen tents, screens, and porta-potties before; there was precedent. Unfortunately, once

you start talking about something like that, the bureaucrats really get into things with both feet. It takes about a year of bureaucratic wrangling to erect a birdhouse in Pitkin County. The hope that something of this nature could be pulled together in time was basically pie-in-the-sky. The Jumbotron idea was scrapped, and there was also no live feed to a local nightclub, as had been proposed toward the end of things. Ultimately, all that was done for any Hunter hunters who might have made the pilgrimage was a few porta-potties across from the Tavern. The Sheriff's Department, city and county officials, and the local papers took every opportunity to broadcast the fact that it was a private event and that no one was welcome.