The Kitchen Readings (13 page)

Read The Kitchen Readings Online

Authors: Michael Cleverly

You might be surprised how many people could lead their whole lives without ever hearing the sound of a submachine gun being fired at close range. Judging from the reaction, some of those people were at Hunter's that evening.

Expensive equipment that had taken an hour-plus to set up was literally thrown into their rental car. Five minutes later the

crew was packed up and heading out the driveway, trailing cords and random bits of high-tech equipment.

Andrea Joyce was left to ponder which of the Beattie men had been right. Sure, she got her interview, but was it a good idea?

Mick Ireland was a Pitkin County commissioner; he was also a lawyer. Before that he was a reporter for the

Aspen Times

. As a politician, he was to the left, pretty far. As a human being he was pretty conservative. He didn't smoke, drink, or do drugs. He seemed to enjoy eating, but you'd never know it to look at him. He was as lean as they come. Probably because he rode his goddamn bicycle about a million miles a week.

It could be said that Mick spent his political career pissing people off. Particularly rich people. His enemies tried to recall him on three occasions. Their efforts never succeeded. Each time Mick ran for office, a group of wealthy conservatives threw piles of money at the opposing candidate. Always anonymously. Mick

would win, and they'd throw piles of money at a recall effort. Always anonymously. And they would fail. Always anonymously. Why were they so upset? Mick could be direct, abruptâokay, rude sometimes. Regular people are used to rudeness; we get it all the time, we're inured to it. The wealthy aren't; it hurts their feelings, or whatever they have in there.

Mick first came to Hunter's attention in the early seventies. A local rancher thought that he would solve Aspen's housing problems by making himself incredibly rich. The guy really wasn't fooling anyone, but in those days people, and the newspaper, leaned toward civility. Mick wrote a scathing column for the

Aspen Times

in which he compared the rancher to Nixon and his “secret plan,” and in general vilified the guy three ways to Sunday. Hunter approved. From then on, even though it would be years before Mick sought office, Hunter knew that he had a political ally.

In the mid-eighties Mick was still reporting for the

Aspen Times.

A local “import/export” guy with what seemed to be excellent Bolivian connections had just finished a couple sets of tennis at a fancy local club. Someone had carelessly left a pipe bomb on the undercarriage of his Jeep directly beneath the driver's seat. When he started it up, he was blown to smithereens. This was a big deal for Aspen. That sort of thing never happened. It made people think.

One thing that people thought about was how many of their friends were either in rehab or jail. What they concluded (some of them) was that maybe drugs weren't good for you. Mick had always been of that opinion. During the course of the police investigation, Mick got hold of the smithereens guy's papers, which included a lot of names, and published fifty-four of them. The implication was that these people were in the import/export

business, too. For a small town like Aspen, this was a big scandal. It was also the kind of behavior that would get you on Hunter's shit list till the end of time. To his credit Hunter never held it against Mick. He understood that he and Mick had fundamental disagreements regarding their respective hobbies, and they basically agreed to disagree. Mick was doing what he thought was right, no matter how much Doc disapproved of the concept of outing small businessmen.

It wasn't long after that Mick decided to go to law school. He figured he'd become a lawyer instead of just creating all these clients for other peopleâ¦.

Â

By 3:00

A.M

. on a Monday in August 1987, Mick was a law student living in a Boulder apartment with no air-conditioning. It was hot. When the phone rang he wasn't thinking “party.” “Hi, is Mick there?” asked a cheery female voice in tones better suited to the middle of the day. Mick quelled his instincts, the sarcastic ones, and admitted to being himself. “Yes, how may I help you?” “I need some beer” was the cheerful response. Of all the people in Boulder, Mick was the last person to be likely to have beer kicking around at 3:00

A.M

. He didn't use it. He biked, he ran, he went to class, and he slept whenever he could. Three o'clock in the morning had always seemed like a great time for the sleeping part.

But, as fate would have it, Mick actually did have some beer in the wee hours of that summer morning. He had recently hosted a party for new law students whom he'd been tutoring and there were leftovers. “Who is this?” he asked. “Kathy. You know, Kathy. Hunter's wife,” she said. People's wives don't generally call Mick at that hourâand Hunter? The only “Hunter” that Mick could think of was, well, Hunter. But it didn't make any sense to Mick. And he didn't know anything about any Kathy.

Kathy explained that Hunter was in town and couldn't write his column without beer. She acted as if she and Mick had been buddies for years and the request couldn't be more ordinary. Mick asked the same question that so many of Hunter's friends have asked themselves on so many occasions over so many years. “Why me?”

Kathy explained that the beer had to be delivered to a motel in Boulder so Hunter Thompson could write. Mick was inclined to accommodate. He had enrolled Dr. Thompson in the CU class of 1988 by adding his name to the seating charts circulated by the less-than-hip professorate. The joy of hearing a professor address a fellow student as “Mr. Thompson” and ask for the holding in some obscure law case lingered.

Mick shook his next ex-girlfriend awake. He offered her the chance to meet the famous celebrity, author, political junkie. By his own admission, the lady in question, Eileen, was smarter than he. She practiced law in areas whose boundaries Mick was soon likely to cross. She didn't fancy junkies of any kind, including political ones. She declined. Mick had a difficult time understanding. The chance to deliver beer to a degenerate in a seedy hotel at three in the morning? What's not to like? She might get to watch him write something. Eileen stuck with “no.”

Mick soon found himself wandering down hallways carpeted in mildew red and accented with duct tape and lit by fluorescent lights. The air-conditioning rumbled and wheezed ineffectually in the background. A little bit of real America, with the new center for creative writing in Boulder serving as a counterweight to the Jack Kerouac School of Disembodied Poetics, just up the road.

The Doctor himself answered the door. This was important. He had made 108 consecutive deadlines since he started writ

ing for the

San Francisco Examiner

and this improbable streak was on the line. Hunter spoke: “Wantsomecoke, hash, smoke-something? Thanksforcoming.” He was surprised, gracious, and a little apologetic. Someone had actually gotten up at three in the morning to deliver beer to him.

Police Story

was on the TV in the background. It lent a pleasant ambient din of sirens, fistfights, and gunfire. Kathy was in the corner, cute and perky, still a total stranger to Mick. Kathy explained Hunter's current process. He was on one of his perpetual speaking tours and he would use his “lectures” as material for the column. He would bait the audience and direct the ensuing give-and-take to his needs, all the while taping. Afterward, he'd retire to his room and work from the recording.

On the whole, this approach worked pretty well. But on that particular evening he had run out of tape during a spirited exchange with four Boulder women. The topic was the social implications of pornography. It had the potential to be a great column, and Hunter was hoping that Mick and Kathy could recreate that portion of the evening. Mick was dubious, not having attended the event. Kathy was optimistic. The two retreated to a corner and left Hunter to Hunter. Recreating isn't easy work. All Mick knew about porn were some case studies saying that you can't use zoning to keep it out of your neighborhood. Nothing firsthand. He decided, instead, to try to get Kathy to apply to law school. Mick knew people in admissions; Hunter hated lawyers.

There was a knock on the door. Hunter turned, “SorryMickIdidn't knowifyou'dmakeitsoIorderedsomebackup.” Like something that crept out of Hunter's subconscious, a short, sweating, wild-haired, twentysomething kid entered the room holding a baggie aloft. “I got them; I got the 'shrooms,” he announced

proudly. Now Mick couldn't tell psychedelic mushrooms from grass clippings, but he had an idea that he knew what was in the bag.

It took the untidy youth a good half-hour to make Doc understand that he didn't want to be paid for the drugs. He wanted to be able to say that he'd done mushrooms with Hunter S. Thompson. (Someone was on something already.) He would not accept money from his hero. Hunter wanted the kid to leave, go back to wherever, so he could try to get back to work. What the kid wanted was for Hunter to sign his chest, his greasy, sweaty chest. That seemed reasonable. Someone produced a red Magic Marker. “Hunter Thompson is weird” is what the kid wanted Hunter to write. Hunter proceeded, in capital letters. As he wrote, the sweat dissolved the marker, creating a Steadmanesque drool. Hunter got to the word

weird

and paused. He had forgotten how to spell it. He asked for input. How was it possible that Hunter Thompson couldn't spell

weird

? The combined talent in the room spelled it out for him one letter at a time. The kid left, inscription dripping.

“He'sgonnagetusbusted. He'llgetstoppedbythecopsandpulluphisshirtandsayI'vebeendoing'shroomswithHunterThompson.”

Hunter's diction was murky as usual, but the image was crystalline. The kid opening his shirt for the cops, swelling with pride.

Mick hadn't actually witnessed Doc consume so much as a single beer since he had arrived, but the baggie full of mushrooms bore a close resemblance to an evidence bag in his mind. Cops don't much like Hunter. Mick had a future. Time to go.

Hunter didn't make his deadline that night, or any other. Apparently that evening marked the beginning of the end of Hunter and the

Examiner.

It should be noted that Kathy wasn't really Hunter's wife. All for the best. Hunter's halfhearted attempt to stab her with a ballpoint pen on the flight back to Aspen probably wouldn't have done the marriage any good.

Â

Years later Mick was having lunch with a high powered Denver law firm. A tableful of sharply dressed attorneys were there to evaluate him as a potential associate. Almost the entire lunch was spent discussing his most important qualification: Did he really know Hunter Thompson?

Back in Aspen, one year a district attorney actually got a search warrant for Owl Farm. Along with a lot of nothing, the cops seized a videotape labeled “Child Pornography.” The tape turned out to be a PBS panel discussion on the subject. Probably touching the same points as Hunter and the four Boulder women.

When Mick returned to Aspen and became county commissioner, he once again began to receive 3:00

A.M

. phone calls from Hunter. Mick was a political ally despite his offensive lifestyle. Politics far outweighed his bad habits.

And so, Mick writes: “Hunter and Nixon and the Evil Developers he hated so well are gone now and so, as a mutual friend put it, I know when the phone rings at 3

A.M

., it's probably bad news, in plain English.”

The “Derby” parties and the Super Bowl parties were late-afternoon events. Family time. If it's family time at your house, then it's family time at Owl Farm. People would feel free to bring their children. Hunter had no problem with children, as long as they were willing to gamble along with everyone else. Given Doc's nocturnal lifestyle, there usually wasn't much chance of running into a child in the kitchen, so it wasn't really any hardship to have them around on these special occasions. It encouraged our best behavior. Besides, I think Hunter probably viewed it as an opportunity to fleece the parents twice.

The gambling at the Kentucky Derby and Super Bowl parties was different from the usual football and basketball wagering.

During the regular seasons there'd be the standard house bet on the game, twenty dollars (a figure that Hunter would always be glad to adjustâ¦up), possibly an “over and under” bet, and lots of proposition bets during the course of the game. The quality of thought that went into the wagering varied greatly. Nobody was better informed than Hunter. He poured over the sports pages, the ever-changing betting lines, the injury situations, the matchupsâand he wouldn't hesitate to call friends across the country to get inside information to give him an edge.

On the other side, former alpine skiing coach and sports commentator Bob Beattie, filmmaker Bob Rafelson, and Sheriff Braudis could always be counted on to make intelligent, well-informed wagers. There were many others who could be best described as middling ignorant. Then there were the Ewing brothers, Wayne and Andrew. Wayne is a filmmaker who, even when based in L.A., maintained a place in the Roaring Fork Valley. His brother, Andrew, would visit several times a year. Wayne and Andrew were deeply entrenched in Hunter's inner circle. As a rule they were both smart, savvy gamblers; they did their homework. But they had a tendency to get caught up in the moment. Wayne and Andrew would enter the kitchen and immediately start tough negotiations with Hunter over points on the game bet. This could sometimes be a long, painful process. Hunter liked the edge; these guys liked the edge. Then came the over/under: same thing. When this was settled we'd all assume our positions to watch the game.

Sometimes the first proposition bet could come with the opening kickoff. Sometimes it took a while to work into it. Either way, it was a pretty sure thing that one of the Ewing boys would be involved. In the beginning the propositions would be reasonable. A first down this series, whether the next play would be a

pass or a run, something that could go either way. Hunter would almost always take up the challenge, and then some of the rest of us would jump in. As the game proceeded, these wagers would slowly increase in recklessness: long-shot first-down attempts, low-percentage chances of scoring on this drive. After a while, the drink flowing, everything else flowing, raucous goodwill abounding, these wagers would move from reckless to irrational: a team scoring late in the game from deep in their own red zone, long, long, field goal attempts.

It was at these times that the intelligent, well-prepared Ewing brothers became the “lemming brothers.” This was Hunter's time. He would glow. Hunter thought it morally deficient not to take advantage of someone who was succumbing to his own stupidity. The proposition bets were usually of the five-or ten-dollar variety. The point wasn't just to take all of anyone's money; it wasn't nearly that honorable. The point was to thoroughly embarrass and deeply disgrace the other guy. That was worth the wager. And that was usually the way things turned out. But, as noted, that was during the regular sports seasons. Then there was the Derby, something altogether different.

There was plenty of side betting at the Kentucky Derby parties, but a lot of that kind of energy, out of deference to the non-regulars, was focused on “the pool.” For the Derby, the pool involved drawing horses' names out of a hat, a matter of pure luck. Hunter would set it up so that the winner walked away with several hundred dollars. But in light of all the kiddies, the buy-in was never too expensive. If Mommy wanted to buy in for you, great. If a child used his own money, earned shoveling snow over the course of a long, cold winter, that was okay, too. We always respected a young person's right to be fleeced as much as an adult's.

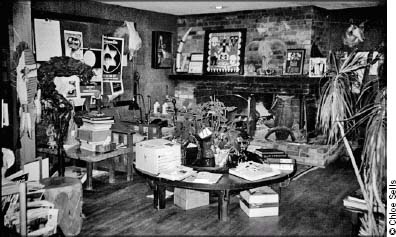

The living room was used mainly by the women to get away from us, and for large overflow events.

The crowd at the Derby parties consisted of the inner circle and their significant others, old friends with their families, and occasional newcomers and guests. Many of the kids who attended these parties had been regulars from an early age and were very hip. They knew the score and were often put in charge of the pools. One good lad, Matthew Goldstein, not only ran the Super Bowl pool but also won it with annoying regularity. Aspen mayor John Bennett, his wife, Janie, and their young daughter, Eleanor, came under the “old friend” category, often attending the special events but not part of the less-savory regular gang.

As the Kentucky Derby itself lasted only minutes, the party would begin a couple of hours before hand. There was always good food and more than enough to drink, of course. Hunter's bedroom TV would be brought into the living room for these occasions, as the assembled crowd was far too big for the kitchen. There was plenty of eating and drinking before the race, a little

side betting, and of course the pool. As post time approached, the party would be in full swing. Everybody had a horse, especially the kids.

On one particular Derby day, the mayor's daughter, Eleanor, had coughed up the cash and drawn her horse; she was pretty excited about this new grown-up thing, gambling. Unfortunately, she had a previous engagement that coincided with the exact time of the race itself. It was a strange time to leave, just before the big event, but Eleanor's mom, Janie, a force in her own right, took her daughter in hand, made their excuses with the promise that they would return shortly, and off they went. The race in all its glory came and went in less time than it is possible to have any other kind of meaningful experience. As fate would have it, young Eleanor won the pool without being present. Hunter, after surely wrestling with the prospects of ripping her off, decided that we shouldn't tell Eleanor about her winning but should instead replay the tape of the race and let her experience it as if she were watching it live.

All major sporting events were taped at Owl Farm. An extremely prudent policy, considering the state of consciousness people were capable of achieving by the end of any given competition. It gave a reassuring credibility to the reckoning. Eleanor Bennett and her mother returned to the party after a while. Hunter grabbed a crony and told him to put in the tape of the race. In the meantime he began to set up Eleanor for the big event, building the suspense with all his considerable skills.

Having worked the mayor's daughter into a fever of anticipation, Hunter hit the remote. The room fell silent. Silent, except for the peak volume sounds of the hard-core porno film that appeared on the enormous TV screen. There's something about the audio track of a top-drawer porno film that, when played at

high volume, is even more obscene than the visuals. Of course the visuals were pretty good, too. Wrong tape. An easy mistake. There certainly were plenty of tapes lying around in front of the TV. God knows what else was in there. Pandemonium ensued.

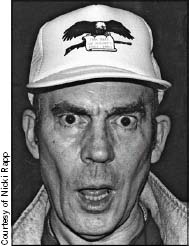

With the strangled cry of the wounded and feral, Hunter snatched up the remote, wildly thumbing every button, with zero effect. As later investigations revealed, someone had put a glass down in front of the electric eye that received the signals from the remote. But for now there was only chaos. Hunter flung the remote across the room. Close to a dozen remote controls were in front of him, scattered to either side and on top of his typewriter. He snatched them up one at a time, crazily hitting buttons at random. Small appliances sprang to lifeâradio, CD player, air-conditionerâeach one mocking him in turn, as the porn film played on, still at top volume. Some fled the scene in terror or hysterical laughter. Some discovered a renewed interest in television. All the while, the mayor's sweet young daughter stood impassively, watching closely, waiting for the race to begin.

Hunter expresses his frustration with the remotes as the mayor's daughter watches.