The Kidnapping of Edgardo Mortara (51 page)

Read The Kidnapping of Edgardo Mortara Online

Authors: David I. Kertzer

The old woman was Anna Ragazzini, a 67-year-old widow who lived in her ground-floor apartment with her 18-year-old servant, Teresa Gonnelli. Teresa recalled hearing a big crash, as if someone had slammed a window shut, and right afterward, a big thud in the courtyard. The dog immediately began to howl, and the two women ran to see what had happened. There lay Rosa, her skirts up over her head. “Ragazzini pulled her clothes down to cover her shame,” Teresa remembered, “and we could then see that her head was bound with a white kerchief tied by two knots in back.” Rosa murmured, “ ‘Help me, I feel like I’m dying,’ and then Ragazzini went to the door to get help. I stayed there, alone, and said to her: ‘Poor girl, what happened? Did they throw you down?’ and twice she answered, ‘Yes.’ ”

Signora Ragazzini’s young servant went on to testify that in the two weeks that she had been living there, “day and night, I always heard loud noises, arguments, and quarreling in the Jew’s house.”

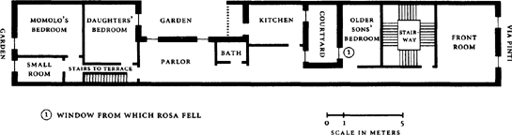

The Mortara Apartment in Via Pinti, Florence April 1871

“I know the Jew Momolo Mortara by sight,” Signora Ragazzini testified that same day. Although the Mortaras had lived in the building for two and a half years, she had never spoken to them, nor, for that matter, had she ever met their new servant. The widow had, however, seen Rosa return to the building the previous afternoon with the Mortaras’ little girl. Within fifteen minutes of their return, she heard the alarming sounds from the courtyard.

When Rosa, lying bleeding on the pavement, appealed to Signora Ragazzini for help, the woman had frantically raced to the street to find someone. Once outside the building, she looked up at the Mortaras’ apartment: “I saw two people—I couldn’t make out whether men or women—and I said, ‘Come down! Can’t you see that it’s your servant!’ but no one came.”

Actually, someone did come, although it was not one of the Mortaras but Signor Bolaffi, the family friend who had accompanied Rosa and Imelda home. He came down with a boy, reported Signora Ragazzini, “and asked what had happened. I told him, ‘You know better than I do, because the servant is from up there.’ He replied that he was going to the police station. That surprised me,” said the suspicious widow, “because it seemed to me that he should have shown more interest in the situation.”

Signora Ragazzini did not hesitate to tell the police just what she thought. “There’s a constant uproar in the Mortara home, and arguing and swearing day and night. I believe,” she told the inspector, “that the servant was wounded on the head before she fell into the courtyard, because she certainly didn’t put that kerchief on down there, and she didn’t do it on her way down either!”

Finally, the inspector called in Flaminio Bolaffi. Rosa had been dead less than a day. Bolaffi, a Jewish friend of the Mortaras, was also a businessman, at 53 about the same age as Momolo.

2

He testified that when he had returned

home the previous day, a little after 4 p.m., he had found Rosa and a very frightened Imelda there. His wife told him Rosa’s story of her encounter with her former employer and the man’s attempts to follow her into the house. Indeed, Bolaffi’s wife had herself spoken to the men when they came to the door. Imelda did not want to return home with Rosa alone, because she was frightened of the two men, nor did Rosa want to go either. “However,” Bolaffi recalled, “I persuaded her and accompanied both of them back to the Mortara house.”

When they arrived, Bolaffi found Momolo in bed. He had been bedridden for some time because of a painful tumor on his knee. In his large bedroom, his wife and two older daughters also sat, sewing. None of the other children was at home. Bolaffi explained why he had accompanied Rosa and Imelda home, and Momolo asked his wife to go fetch Rosa so they could hear what had happened directly from her. Marianna found Rosa, crying, upstairs on the terrace and told her to come down, saying, according to Bolaffi, “that if she was innocent, she had nothing to fear.” But Marianna returned to the bedroom alone.

A few moments later, Bolaffi reported, they heard a loud noise, and the Mortaras’ dog started barking. He thought the noise must have been made by Rosa, slamming the front door on her way out, but when he went to the stairs to look, no one was there. He noticed, however, that the window of the room that the older boys slept in, which looked out over the courtyard, was open, and, peering out, he saw Rosa lying below. “I immediately ran down the stairs to notify the police, and once I got downstairs, I saw two women at Rosa’s side. I urged them to assist her while I went for the police. And I can assure you,” he added, “that no argument occurred between Rosa and any member of the Mortara family while I was there.”

It was now time for the investigating magistrate, Clodoveo Marabotti, to go to the morgue to hear directly from the two surgeons responsible for examining Rosa’s wounds. It was a gruesome scene; Rosa’s body lay atop a marble slab, her long reddish hair spread out around her bloodstained head. A tall and robust woman, she was dressed in the clothes in which she had fallen: a slip, two petticoats, and a gray-and-white plaid dress. The examiners had removed the bloody white kerchief from her forehead. When they inspected her dress, they made a puzzling discovery: in a pocket, they found a razor, stained with blood.

Marabotti was especially interested in what the doctors could tell him about the wound to Rosa’s forehead. It was an irregular, rough, serpentine gash, they reported, five centimeters long, with contusions around the edges, so deep that the frontal bone beneath showed through.

Having done all they could with the body in the state in which they had

found it, the doctors began the autopsy. They first opened up Rosa’s head and discovered that whatever had caused the gash over her eyebrow had also produced an extensive fracturing of the skull beneath. Her brain cavity was filled with blood. As for the cause of death, the doctors concluded that she could have been killed by the traumas caused by a fall from high up, but, they added, the wound to her forehead might have been lethal by itself.

The Magistrate then told the medical examiners of the testimony he had received about the violent behavior of Rosa’s employer, and asked them if they could say anything about what kind of implement might have caused the head wound, whether the gash was caused by the fall, or whether it predated the fall. Marabotti particularly urged them to consider the fact that, despite the vicious nature of the wound, the kerchief that covered it, though bloody, was itself not torn in any way.

The doctors hedged a bit, but clearly they saw Marabotti’s point. The wound to her forehead “could have been produced by the fall,” the doctors reported. Yet, “given that the woman, just before her fall, had folded a kerchief and tied it around her frontal region, in the manner found on the one that has been submitted to us, stained by blood … it is more believable and more consonant with the laws of mechanics that the wound … came before the fall and was produced a short time before the other injuries, by a lacerating and blunt implement.”

When the investigating magistrate returned to his office, he received a report from his assistant, who had reconstructed the events, based on the testimony he had gathered. The assistant’s report told of Rosa’s unpleasant encounter with her former employer and the man’s warning about reporting her to the police. When Rosa returned to the Mortaras, she seemed very upset, “and being near a bedroom window, she must have thrown herself into the courtyard below.” The inspector had learned from Imelda that, just before Rosa’s death, the girl had seen her with a kerchief in hand, which she had folded lengthwise. When Rosa saw that Imelda was watching, she pretended, the girl said, to blow her nose. The inspector did not think much of the neighbors’ wild accusations. It was a simple case of suicide.

Unfortunately for Momolo, Marabotti reached a different conclusion. Something was suspicious. Why would a healthy young woman toss herself out the window because she was accused of stealing a few lire and some scraps of used clothes? If every servant accused of such behavior were to toss herself from a window, Florence would be littered with their bodies. And what about the suspicious gash and bandage on Rosa’s forehead? How could that be explained except by an earlier skull-cracking, and probably lethal, blow, followed by a panicked attempt to stanch the bleeding with a kerchief? And then there were all the neighbors’ reports about the nonstop quarreling and

bellowing that emanated from the Mortara apartment. When put together with reports that one servant after another had quit, a clear pattern was emerging: Momolo was a violent type, and his family’s servants bore the brunt of his ire.

Wasting no time, the Magistrate signed arrest warrants for both Momolo Mortara and Flaminio Bolaffi. Citing the testimony of the widow Ragazzini and her servant, Teresa Gonnelli, and the evidence of the gash on Rosa’s forehead, the warrant charged that, “far from voluntarily throwing herself out the window … Rosa Tognazzi was thrown out by others.” It concluded that there was “serious evidence pointing to Momolo Mortara and Flaminio Bolaffi as the authors of the homicide.”

The next day, April 6, three days after Rosa’s death, the Magistrate arranged for a doctor to examine Momolo at his home to determine whether he was well enough to be taken directly to prison. The physician found Momolo still in bed and concluded that he was, in fact, incapacitated by his ailing knee. Both Momolo and his friend Flaminio were arrested the following day. Momolo was taken not to the hospital, as the doctor had recommended, but to the prison infirmary. Flaminio went directly to a jail cell.

The Magistrate, meanwhile, continued his interviews with the residents of the Mortaras’ building. Violante Bellucci, a single, 51-year-old man who rented rooms just below the front of the Mortara apartment, confirmed the other neighbors’ reports. “There isn’t any peace there day or night. You hear noises, quarreling, and swearing all the time, and they seem to live like animals.” Late on the afternoon of April 3, Bellucci testified, he had been looking out his window onto via Pinti and saw Rosa returning home with the Mortara girl, who was carrying a school bag, along with one of the Mortaras’ sons. About a quarter hour later, still in his front room, he heard a woman from the ground floor calling for help, shouting that someone had fallen from the fourth floor. When he heard this, he rushed to a window that looked onto the courtyard, leaned out, and spotted Rosa lying below. Before going down to see what he could do, he had looked up at the Mortaras’ window. There, he testified, at first he saw the Mortara schoolgirl looking out, and then “I saw a man who was not Mortara but seemed to me to be a Jew, with an olive complexion, a small man … and I noted that he was shaking his head while I was looking at him.”

There was one thing about the case that bothered the Magistrate: If Momolo was as infirm as he was made out to be, just how had he killed the woman and then lifted the bulky servant out the window? “He always walked with a limp,” said Bellucci, “but I can say with certainty that on that same day, April 3, around 9 p.m., I heard him on the stairs, and then I saw him leaving the house with his little son. He had a walking stick.”

The other neighbor interviewed that day was 52-year-old Luigi Balocchi,

who lived in the building with his wife, children, and servant. “I know the Jew Momolo Mortara,” he said, “purely by sight.” Like his neighbors, he often heard loud quarrels and swearing coming from their apartment and concluded that Momolo “was a violent and quick-tempered character. It seems,” he added, “that harmony did not reign between husband and wife.”

Balocchi recalled that he and his family had been at the table eating at 5 p.m. on April 3 when they heard a fearful crash from the courtyard. “I told my children and my wife not to move, imagining that something bad had happened.” Hearing cries from below, he peeked cautiously out the window into the courtyard and saw a woman covered with blood. “I immediately closed the window and returned to the room where my family sat, frightened, and neither I nor any of them got up until all the noise had stopped.” He told the Magistrate that, “since the matter didn’t concern me, and since my wife had begun to sob uncontrollably,” he had paid no more attention to the injured woman. But that evening, when he went to pick something up at a nearby store, he found many of his neighbors gathered there, chatting about the woman’s death. They claimed that Rosa “was thrown from the window.” Ever cautious, he added, “but whether what they said is true, I cannot say.”

The only friendly witness interviewed that day was a 49-year-old widow, Adele Berselli, a friend of the Mortaras’ since they had moved to Florence. True, she admitted, Momolo “is an irritable man and shouts loudly, but,” she quickly added, “he is a good man.” Hers was a lonely voice.

At 2 p.m., shortly after his arrival at the Murate prison, Momolo Mortara was visited by the Magistrate in his infirmary bed. In response to Marabotti’s questioning, Momolo gave his version of what had happened on the day that Rosa died. Around 4:30 that afternoon, as he was lying in bed, he had heard Rosa come in with Imelda, along with Flaminio Bolaffi and Bolaffi’s son, Emilio. Bolaffi told Momolo, Marianna, and their daughters what had happened. Just then, seeing Rosa pass by the room, they called for her to come in but got no response, so his wife went out to get her. Marianna “found that [Rosa] had gone out on the terrace, and she told her to go into the kitchen to make some broth. They went back into the kitchen together, and my wife tried to cheer her up by saying that if she was innocent, she shouldn’t even think about it.”