The Italian Boy (31 page)

Authors: Sarah Wise

Next, Serjeant Arabin addressed the prisoners and asked how they pleaded; each said “not guilty.” Then the jury was sworn in—twelve good men and true, between twenty-one and sixty years of age and, since they each inhabited a property of ten pounds per annum freehold or twenty pounds per annum leasehold, deemed “respectable.” No one else might sit in judgment on his fellow Londoner. At ten o’clock, the three judges took their place on the bench: Sir Nicholas Conyngham Tindal, lord chief justice of the Common Pleas and Tory member for Cambridge University; Sir John (Baron) Vaughan; and Sir Joseph Littledale. Each man had around thirty-five years’ legal experience. Sitting alongside them were the lord mayor of London, John Key; two sons of the prime minister, Earl Grey; and the duke of Sussex, younger brother of the king and England’s highest-ranking Freemason. Augustus Frederick Hanover was an enthusiastic amateur follower of many matters scientific, literary, and political. (He had been keen to leave his body to medical science but in the event ended up in a sealed vault at the brand-new Kensal Green cemetery, in 1843.) The duke had requested and been granted a place on the bench for the Bishop, Williams, and May trial in order to see for himself the workings of England’s judicial system. But it is possible that as grand master, he was concerned as to how the trial would affect London’s surgeons, many of whom were Masons. (The Anatomical Society met at the Freemasons Arms, in Great Queen Street, Covent Garden.) The duke of Sussex clamped a pocket telescope to his eye and took particular interest in the appearance of Williams, who was seen to return the royal gaze with a glare.

The average Old Bailey trial lasted eight and a half minutes, from opening address to sentencing, though some “capitals”—cases that could end in the donning of the black cap—might take hours.

7

Today was going to be different: everyone knew there was little chance of a verdict coming in before nightfall. Charles Phillips, barrister at law, knew it, and only the night before had withdrawn from acting as the prisoners’ defense attorney since he felt unable to commit himself to a trial that was likely to last the whole day. It is probable he had a number of more lucrative cases lined up in the second courthouse, adjacent to the Sessions House; he would earn a great deal more money from several eight-and-a-half-minute jobs than from an all-day capital case, and there was nothing to stop him from simply abandoning his clients without notice—plenty of attorneys did likewise every day.

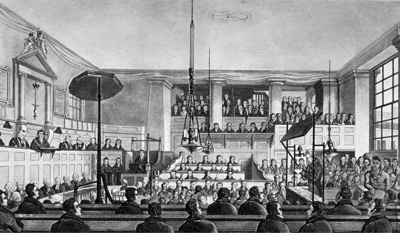

Interior view of the Sessions House, Old Bailey

Prisoners were obliged to seek out legal representation (and to corral witnesses) from their prison cell—no easy task—and Bishop and Williams had asked for the trial to be delayed because of their problem in finding a barrister: Phillips had been acquired only with difficulty. Their request had been rejected, however, even though Minshull and Superintendent Thomas had publicly stated that the case should go to court only when it seemed “perfect.” Both had been hoping for a postponement, and even the recorder of London, the city’s most senior judge, had given his opinion that it would be wisest to wait until January. Whichever mysterious power ordered these matters, though, had decided that the swifter the better with this trial. At the last minute, John Curwood and J. T. Barry, a barrister who campaigned against the death penalty, volunteered to act as defense counsel. To modern eyes reading the trial, it looks as though Curwood and Barry barely acted at all; but there were reasons for their apparent passivity. An attorney hired by a defendant did not mount a defense case as we understand it; he was restricted to calling defense witnesses, cross-examining prosecution witnesses, and reading to the court any statements the prisoner wanted to submit, but he could not address the jury. Since he had no right to know what evidence was going to be given against the prisoner, the prisoner’s statement, prepared before the trial began, had limited effectiveness. Not until 1836 would a barrister in a criminal case be able to make a narrative defense on a client’s behalf; and not until 1898 would the accused be able to take the stand in an English court of law, the idea having earlier been held that defendants should not be allowed to incriminate themselves. But with the defense attorney’s actions so restricted, this right to silence acted against the prisoner, since he or she had no chance to put forward an alternative version of events or to impress a jury with an appearance of honesty through speech or gesture. Silence had a tendency to look like guilt.

The prosecution, too, faced a number of difficulties. It was a growing criticism in legal circles that cases often had to be abandoned and prisoners discharged because witnesses for the prosecution failed to show. For, unless subpoenaed, a witness (both for the defense and for the prosecution) was not obliged to come to court; and, given the possibility of reprisals on the part of the accused, plus the loss of earnings as a result of attending court, many people chose to absent themselves from the witness box. Subpoenas proved hard to enforce, and there was even a name for evading a summons: “running up and down” was street slang for making sure you were not at home, and not to be found anywhere around town, when an official came to deliver a subpoena. Many witnesses who did come forward were found to be drunk by the time they testified; the order of trials at the Old Bailey was only very loosely fixed, and those waiting to be called would often repair to the King of Denmark, the George, the Bell, the Plough, or any of the many other pubs and inns around the Sessions House. It wasn’t just the sobriety of witnesses that gave cause for concern; evening sittings, which would be abolished in 1845, were notable for the inebriation of lawyers after lunch and dinner—at which wine was plentiful—and one judge was regularly seen clutching the banisters as he lurched back to the Old Bailey bench after meals.

8

Forty individuals had turned up to assist the prosecution of Bishop, Williams, and May; six had come forward for the defense—Sarah, Rhoda, and the three little Bishops were not among them, since spouses and offspring were deemed “incompetent witnesses.” Surgeon Edward Tuson of the Little Windmill Street School had been subpoenaed by the defense but protested that he had no idea what the prisoners expected him to be able to say in their favor. Perhaps they were prepared to make embarrassing disclosures about his practice if he would not speak for them; perhaps he had accepted too many “smalls” and “large smalls” than was compatible with respectability; perhaps he had made off-color jokes about the produce or even made comments that could be construed as instructions to murder.

Henry Bodkin opened for the prosecution, saying that he wished to place particular emphasis on the exchanges between Bishop and May overheard by porter Thomas Wigley at the Fortune of War on Friday, 4 November; the conversation that evening had excited suspicion in all who had heard it. (All of Thomas Wigley, Bodkin must have meant; no one else had claimed to have heard it.) Next, John Adolphus rose to instruct the jury not to allow the “interest” that the case had “excited out of doors” to affect their judgment in this “painful and extraordinary enquiry.” It was a revolting crime, he said, precisely because it had not stemmed from any strong feeling or passion: “Nothing but the sordid and base desire to possess themselves of a dead body in order to sell it for dissection had induced the prisoners at the bar to commit the crime for which they were now about to answer.” Bodkin acknowledged that the case relied on circumstantial evidence, “but he contended that a large and well-connected body of circumstantial evidence was in many cases superior to the positive testimony of an eye witness.” He concluded that he relied utterly on the good sense and integrity of a British jury, “which a long life of practice had left him no room to doubt.”

William Hill, dissecting-room porter at King’s, was the first witness called by the prosecution. He repeated his earlier evidence of the events of the afternoon of Saturday, 5 November, though this time there was a little more local color, and the role that May, though “tipsy,” had taken in the negotiations was foregrounded. (Williams, Hill admitted, had been party to none of the bargaining; like Shields, he had been a silent partner on that day.) It came out that with regard to resurrectionists, even so modern a building as King’s anatomical department had “a place appropriated for them.” Hill recalled asking Bishop and May, “What have you got?” and “What size?”; on hearing that it was a boy of around fourteen, Hill had merely asked the price. Hill said that the freshness, the strangeness of the boy’s bent left arm with clenched fingers, together with the absence of any sawdust in the hair (which would indicate that the corpse had been in a coffin), had triggered his suspicion. Hill’s testimony also revealed Richard Partridge haggling in person with May over the price of the child, no doubt to the discomfort of the anatomist, who was next into the witness box. Partridge, when his turn came, told the Old Bailey, “I do not recollect whether I saw the prisoners before I went to the police,” in response to Hill’s clearly remembered “He was talking with May in the room.” Partridge then explained his findings during the postmortem on Sunday night in the Covent Garden watch house. “There was a wound on the temple, which did not injure the bone. That was the only appearance of external injury. Beneath the scalp on the top of the skull, there was some blood effused … the skull was taken off and the brain examined. That was perfectly healthy, as well as the spinal part. In cutting down to remove the bone which conceals the spinal part at the back of the neck, we found a quantity of coagulated blood within the muscles, and on removing the back part of the bony canal, some coagulated blood was found laying in the cavity opposite the blood found in the muscles of the neck. There was blood uncoagulated within the rest of the spinal canal. The spinal marrow appeared perfectly healthy. I think these internal marks of violence were sufficient to produce death. I think a blow from a stick on the back of the neck would have caused those appearances and I think it would produce a rapid death, but perhaps not an instantaneous one.”

He had noticed that the face was flushed and swollen and the heart empty of blood.

“What do you infer from the heart being empty?” asked Bodkin.

“I do not infer anything from it, except that, accompanied with bloodshot eyes, it has been found in persons who have died suddenly and evidently from no violence.”

Curwood, cross-examining on the blood in the spinal canal, asked, “Mightn’t this have been caused by other means as well as by a blow—by pressure otherwise applied?” Perhaps Curwood was recalling a forensic detail from Burke and Hare: in Edinburgh, surgeon Robert Christison had stated that, in his view, extravasated blood—that is, blood that has escaped from blood vessels into surrounding tissue—would have the same appearance regardless of whether the injury happened before or after death. Christison had pointed this out when Burke and Hare had claimed that the injuries found on Mary Docherty had been caused when her body had been doubled up to be packed into a tea chest for delivery to Knox; she had died of drink and old age, not from violence, they had said. In Burke’s confessions, the Edinburgh killers’ modus operandi was revealed—suffocation with bare hands and no blows struck, to keep the corpses looking as though they had died from natural causes. Partridge had evidently never read this aspect of the famous case or, if he had, he had rejected Christison’s (and Burke’s) findings, for he answered Curwood: “I think not. I cannot conceive any thing but a blow would produce those appearances.”

George Beaman knew a thing or two about spinal injuries, having killed many animals with a blow to the back of the neck to observe the results upon dissection. But he, too, thought spinal injury had been the cause of death: “On the top of the skull we detected a patch of blood.… This appearance must have been produced by a blow given during life.… On removing the skin at the back part of the neck, I should think from three to four ounces of coagulated blood were found among the muscles. That blood must have been effused while the subject was alive. On removing a portion of the spine to examine the spinal marrow, a quantity of coagulated blood was laying in the canal, which, by pressure on the spinal marrow, must cause death. There was no injury to the bone of the spine, nor any displacement. All these appearances would follow from a blow with a staff, stick or heavy instrument.” Cross-examined by Barry, Beaman admitted that there was no injury to the skin at the back of the neck; he saw nothing odd in that, claiming that the boy had died too quickly to have developed a bruise or weal.

The body had been in “very good health,” Beaman added, and had been generally clean, apart from some obviously smeared-on mud or clay. All the other organs had been in good condition, though Beaman had never before seen a heart empty of blood; along with Partridge, he took this to indicate a very quick death—probably within two or three minutes of the fatal blow.

Beaman estimated that the body had been dead for thirty-six hours by the evening of Saturday the fifth, when he had opened it prior to the full postmortem the following day; though, as he pointed out to the court, the coldness of the weather “was very favourable to the preservation of dead flesh.” He believed that the teeth had been removed two to three hours after death and that the boy had eaten a meal around three hours before being killed. (Thirty-six hours before the “evening” of Saturday the fifth was between 5

A.M.

and 10

A.M.

on Friday, 4 November, if “evening” could be interpreted as anytime between 5

P.M.

and 10

P.M.

) Cross-examined, Beaman would not swear to the time of the teeth’s being removed but said that he was certain twelve hours had not passed between death and extraction. James May claimed to have removed them at around half past six on the Friday evening.