The Italian Boy (20 page)

Authors: Sarah Wise

“There must have been three,” said Woodcock.

Woodcock had moved into No. 2 with his wife and son on Monday, 17 October. Despite living next door to Bishop and Williams for three weeks, Woodcock claimed to have seen only Williams, Sarah, and Rhoda at No. 3; the first time he had laid eyes on Bishop had been at the Bow Street magistrates office. Woodcock’s unfamiliarity with the man next door may well be explained by the very different rhythms they followed: Woodcock left at six in the morning to go to his job in a local brass foundry; Bishop, by necessity, worked at night. Alternatively, Woodcock may have heard local talk that made him wish to shun the Bishop ménage altogether. On Sunday, 6 November, Rhoda had asked Woodcock if she could borrow a shilling; his response is not in the records.

Other neighbors had equally fragmentary information to offer. Robert Mortimer, an elderly tailor who lived in Nova Scotia Gardens, testified that, to the best of his belief, Williams lived at No. 3 with the Bishops. Toward the end of September, Mortimer had made Williams’s wedding coat for him. He had gone to No. 3 on a number of occasions to collect the money Williams owed him for his work, without success. That’s all he knew.

Sarah Trueby told the magistrates that she had let No. 3 to Sarah Bishop in July 1830, and No. 2 to Thomas Williams in July 1831, and he had lived there for about two months. Trueby said she had often seen Williams in Bishop’s house since he had left No. 2. Of Rhoda, all she could say was, “I have seen her without any bonnet on.”

George Gissing, son of the Birdcage’s publican, knew both Bishop and Williams and recognized them on the night of the fourth, but said he had never seen Rhoda.

Ann Cannell, the local girl who had also seen the men that night, said she had not recognized Bishop or Williams.

“There is no such thing as neighbors,” wrote James Grant about London in the

Morning Advertiser

. “You may live for half a century in one house without knowing the name of the person who lives next door.” And John Wade concurred: “There is no such thing as a vicinage, no curiosity about neighbours. It is from this circumstance London affords so many facilities for the concealment of criminality.”

1

Minshull had asked Superintendent Thomas whether it was true, as he had heard, that Bishop’s house lay “in a very lonely situation,” the sort of place where evil deeds could be committed unseen. Thomas had had to reply that in fact the Gardens was “a colony of cottages,” divided from one another by low palings and that one had only to step over these to have access to at least thirty other dwellings. Also, Nos. 2 and 3 were at the very entrance to the Gardens, just off Crabtree Row and within sight of the Birdcage pub.

How unnoticed could someone live in London? How little did one know about one’s neighbors? These questions intrigued those investigating Nova Scotia Gardens.

* * *

Superintendent Thomas

had written up a statement for Margaret King of Crabtree Row to sign, confirming what she had already told the magistrates about seeing the Italian boy in Nova Scotia Gardens. The arrival of King’s baby was imminent, and it was unlikely that she would be able to attend an Old Bailey trial should the case make it into the final session of 1831. But when she stood before Minshull again on 25 November, King said she was unable to swear to the detail of the clothing the Italian boy had been wearing when she saw him on Thursday, 3 November. She had been aware only of a “Quaker-fashion” dark blue coat or jacket, with a straight collar; it had seemed unremarkable. “The boy’s dress appeared to be shabby, such as other boys wear who go about the streets,” she said. It was odd in itself that she could tell the cut of the coat, when she had said that the boy had been standing with his back to her. She had made no mention of his wearing anything on his head. All the clothing that had been dug up at No. 3 was now placed in front of her, and Minshull asked King whether the poorer quality “charity-school” coat was the one she had seen on the boy. “The coat is, to all appearances, exactly like the one which the boy had on,” she said, “but there is no mark about it to enable me to swear positively that it is the same coat.”

“You are not being called upon to swear positively to it, but only to the best of your knowledge and belief,” Minshull told her.

She replied, “All I can say is, the coat is exactly like, as far as regards colour, size, and shape, and it has every appearance of the coat which the boy had on when I saw him on Thursday. And so is the cap.”

King’s nine-year-old son, John, was more forthcoming. He told the court that he had seen the Italian boy too, from the Kings’ first-floor window, and when he asked his mother if he could go and see what the boy had in his cage or box, his mother told him no. Minshull asked the boy to describe all he could about the Italian boy, and John recalled that the boy had been standing with his back to Nova Scotia Gardens and facing Birdcage Walk, the northern continuation of Crabtree Row; he had his right foot turned out, his arms rested on his cage, and he was wearing a brown furry cap with a visor lined in green fabric. Thomas then brought the cap he had found in Bishop’s home over to John King, who said, “It looks exactly like the cap the Italian boy had on.” (John Bishop had smiled oddly in court as Thomas revealed that the cap had been found in his parlor.) The King family had seen all the items of clothing before, since Thomas had taken them straight to their home after exhuming them. Despite this, much play was made in court of the fact that John had been kept out of the courtroom as his mother gave her evidence on the clothing.

Minshull asked John King if he had ever seen the boy before, and the child said: “I think I have seen him about before. He used to carry a doll with two heads in a glass case. I saw him about a month ago. He looked like the same boy. I have not seen him since the Thursday I saw him in the Gardens. He was then standing still, to see if anybody would come out and see what he had to show. I did not see him go away.” When asked how far the boy had been standing from Bishop’s house, John replied, “It would not take me more than half a minute to get there.”

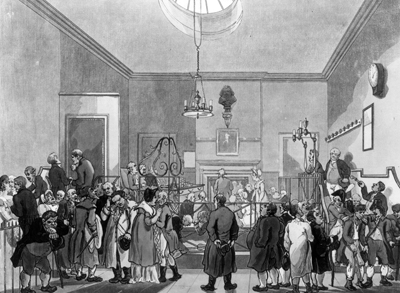

Inside the Bow Street police office/magistrates court

His eleven-year-old sister, Martha, said she was not sure if it was a Wednesday or a Thursday on which she saw the Italian boy at Nova Scotia Gardens. She did not remember any of his clothing except for the brown cap and the string around his neck from which his box or cage was hung. She could not see the color of the cap’s visor lining since the boy had his back to her. But when Thomas handed her the cap, she said it was like the one she had seen.

It must be supposed, since there is no evidence to the contrary, that Margaret, John, and Martha King were describing the same incident, that they were all looking at the boy from either the first floor (John) or the ground floor (Margaret and Martha) of their house, which stood on the south side of Crabtree Row facing Nova Scotia Gardens. Both Mrs. King and her daughter saw the boy with his back turned, but John claimed to have seen the boy full on, from above—even noting the color of the visor. And now all three were placing themselves within their home, though in her earlier evidence, Margaret King had stated that she and the children had been out walking when they had seen the Italian boy.

* * *

Superintendent Thomas

would not relinquish his grip on the two elder Bishop children. He believed they would eventually reveal damning facts about the household since, Thomas stated, and reporters duly reported, Williams had been living with them in the cottage for eighteen months. But here, the superintendent had become confused: Williams had moved into No. 2 in July 1831, not July 1830, and had lived with the Bishops for just a few weeks. It was the Bishops who had moved into No. 3 in July 1830.

The Bishop children had been brought from the Bethnal Green workhouse to be lodged at the Covent Garden watch house in the hope that closer acquaintance with the police would encourage them to speak more openly. It had already been established that Bishop’s youngest son had told another little boy who lived nearby that he had “some nice little white mice at home” but that his father had used the cage as firewood.

* * *

A change had come

over the prisoners during the week of hearings, and, as they stood at the bar on this, their final day at Bow Street, gone were the sneering and jeering, the sarcastic comments about foolish questions and flimsy, ill-remembered evidence. On the preceding Monday, Williams had even loudly sung several songs in the prison van, handcuffed and leg-ironed as he was; he had complained to Bishop that he should not look so “down upon his luck.” Now, though, Williams was extremely pale and fidgeted constantly, his mouth and nose twitching in an odd manner. Bishop looked crestfallen, his eyes were sunken, and he seemed as though he were in a trance; his weight had dropped dramatically. When Minshull told him that he could ask any questions he liked of the witnesses, Bishop bowed to the magistrate and said quietly, “Thank you, sir, we are aware of that.” The

Sunday Times

even attempted a pun at Bishop’s expense, saying that the body snatcher was now looking “cut up.” The Reverend Dr. Theodore Williams, vicar of Hendon, magistrate, and prison visitor, had seen Bishop in jail and asked the resurrectionist if there was anything he wished to discuss with him; Bishop had burst into tears and said no, not yet. Michael Shields looked skeletal and appeared to be in a stupor, standing rigidly at the bar and barely moving for the entire three-and-a-half-hour hearing.

Only May’s nerve appeared to hold, though he was noticeably quieter than before and listened intently to all that was said. May and Bishop had had a fight. May blamed Bishop bitterly for getting him “into this scrape” (according to Dodd, a jailer who listened in on conversations and reported them to Superintendent Thomas).

2

May had shouted to Bishop, “You’re a bloody murdering bastard—you should have been topped years ago.” The signs were that May would, at any moment, turn king’s evidence. What was he waiting for?

After the neighbors had had their say, the summing up began, and all the evidence that had been gathered during the inquiry was read out in court: everything that had been told at the coroner’s inquest, all the witness statements given at Bow Street, all Thomas’s tip-offs and “information received.” Then James Corder revealed that proceedings against Michael Shields were being dropped, no evidence having been found against him. Shields was now officially discharged but was called to stand in front of the bench. Minshull told Shields that he was now a witness—what did he have to say for himself? Shields repeated once again the story that had been prised from him at the coroner’s inquest: that he had met Bishop on the morning of Saturday the fifth at the Fortune of War, had agreed to carry a large hamper—taken from just inside St. Bartholomew’s railings by Bishop—from Guy’s to King’s, a job for which, Shields pointed out to Minshull, he had still not been paid his promised half crown.

Minshull said: “Do you still persist in saying that you were not aware of what the hamper contained?” and Shields replied, “Upon my word, your worship, I knew nothing about what the hamper contained. I carried it as I would any other job.”

“Did you ever carry any load for Bishop or May before?”

“No, your honour, never.”

A clerk warned him: “You know, Shields, you have carried bodies repeatedly to the hospitals. You should remember you are now on your oath.”

“I mean to say that I did not know what the hamper contained that May and Bishop hired me to carry. I never saw Bishop and Williams at my house. I never gave them my address.” At this point, James Corder produced a piece of paper that had been found at No. 3 Nova Scotia Gardens. “Is this paper, on which is written ‘Number 6 Eagle Street, Red Lion Square,’ in your handwriting?” Corder asked.

Shields studied the scrap for some time before saying, “Yes, sir, it is.”

Corder turned to Minshull: “It is quite clear that this man cannot be believed upon his oath, and therefore it would be useless to make a witness of him. I think I should be acting wrong if I did not state that I would not believe anything he could say on oath.”

Minshull agreed: “Every word he has spoken goes for nothing.”

Though extremely annoyed with Shields for failing to be prosecution-witness material, Minshull couldn’t quite let go of the idea of wringing from the man something that would incriminate May, Bishop, and Williams, since the case against them still appeared worryingly slender. “Can you produce any security for your appearance at trial?” asked Minshull, wondering about the chances of binding Shields over to appear at the Old Bailey.

“I cannot,” said Shields. “No one would be answerable for me.”

Then Minshull changed his mind again and decided to let Shields go, warning him to keep Superintendent Thomas informed of his whereabouts—partly for Shields’s own protection. He knew how the crowd could vent its ill-feeling toward resurrectionists.