The Invitation-Only Zone (4 page)

Read The Invitation-Only Zone Online

Authors: Robert S. Boynton

How were the Japanese different from other Asian peoples? Since they couldn’t differentiate themselves by skin color, scholars argued that the difference had to do with the advanced level of “civilization” Japan had achieved. It was not an argument

in favor of racial purity. In fact, Tsuboi championed racial pluralism, comparing Japan’s diversity to Britain’s mix of Irish, Scots, and English. “It is a mistake to believe that a race should be pure and that complexity is bad. Being a mixture is truly a blessing,” he wrote. But the West’s science came with nineteenth-century racial prejudices. Foremost among them was the privileged place that

“whiteness” held in relation to darker races, and the way skin color was thought to correlate with one’s level of civilization. The question facing the Japanese was whether it was possible for them to appropriate the Western concept of race without dooming themselves to an inferior place in the global hierarchy. Were they more closely related to the white West or to their darker Asian neighbors?

The science of race proved to be a double-edged sword, and it is no wonder many Japanese scholars began to replace the Japanese word for biological “race” (

jinshu

) with the word for “ethnic group” (

minzoku

).

12

The vaguer concept of an ethnic group, one sharing a common history and culture, provided more room for the Japanese to maneuver as they reconceived their place in the world.

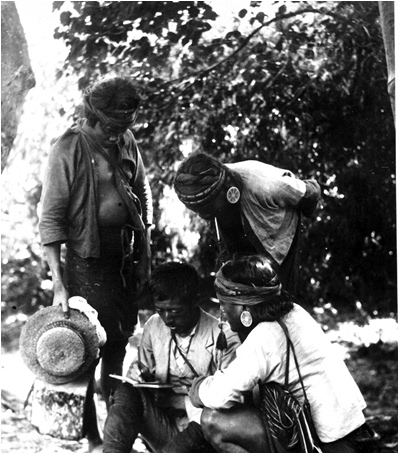

Ryuzo Torii

(Tokushima Prefectural Torii Ryuzo Memorial Museum)

As a boy, Ryuzo Torii spent long afternoons reading Commodore Matthew Perry’s

Journals

(1854), imagining what Japan was like when it opened to the West. Born in 1870, two years into the Meiji era, Torii was raised on Shikoku, the most placid of Japan’s four main islands, located in southwest Japan. He had a privileged childhood,

growing up in a household full of servants, supported by his family’s successful tobacco business. “If I wanted something, my parents bought it for me,” he wrote succinctly in his memoir,

Notes of an Old Student

(1953).

Teachers in the Meiji era tended to be former samurai, noblemen who had been replaced by the emperor’s new professional army. Disarmed, they traded their swords for books, although

they kept their hair in the traditional style (pulled back) and wore kimonos over billowy silk pants and wooden sandals. Torii made a point of skipping their classes, interpreting their appearance as proof they were hopelessly out of touch with the exciting changes sweeping Japan. His favorite teacher wore modern, Western-style jackets and ties and had adopted a similarly forward-looking pedagogical

style that favored empiricism and experience over rote memorization. On nice days, class would be held on nearby Mount Bizan, and the surrounding plants, trees, rivers, and hills were used to exhibit the lessons of botany and geography. Torii was thrilled to discover how much one could learn simply by exploring the natural world, and he yearned for adventures like those he heard about in

the Saturday sessions when the teacher read aloud from books such as

Robinson Crusoe

.

Torii quit school when he turned nine. “One of my teachers told me I wouldn’t be able to survive without an elementary school certificate. I told him I could do better at home by myself,” he wrote. He found inspiration in Samuel Smiles’s book

Self-Help

(1859), a Victorian paean to perseverance, which was a bestseller

in Japan. “Every human being has a great mission to perform, noble faculties to cultivate, a vast destiny to accomplish,” wrote Smiles. “He should have the means of education, and of exerting freely all the powers of his godlike nature.” Torii’s family supported his decision, buying him all the books he wanted, including the first Japanese-English dictionary. In the morning, a tutor would

give him English lessons at home; in the afternoon, he’d scour nearby tombs for pottery and other artifacts; in the evening, he’d pore over scientific encyclopedias, history books, and archaeology studies, curating his growing collection.

One afternoon, Torii stumbled upon Yukichi Fukuzawa’s

All the Countries of the World

(1869), an illustrated geography textbook with a color-coded portrait of

humanity. The book’s first sentences changed Torii’s worldview forever. “There are five kinds of human races: Asians, Europeans, Americans, Africans and Malaysians. The Japanese are part of the Asian race,” it read. Torii was familiar with “Westerners” and “Asians,” but he was surprised by the additional diversity. “I had always thought that everyone else in the world was more or less the same,”

he wrote. What did it mean to belong to a race? he wondered. With this question, Torii was swept up in the Meiji-era effort to generate a Japanese national identity with which to navigate the modern world.

In September 1890, Torii, twenty, embarked on the three-hundred-mile journey from Shikoku to Tokyo. He had been following the development of Japanese anthropology from afar, reading the books

and magazines in which the new scientific method was being applied to geology and archaeology. Torii had even submitted an essay on his fieldwork on Shikoku to the Tokyo Anthropological Society’s journal, which Shogoro Tsuboi edited. Impressed with the young man’s pluck, Tsuboi became Torii’s mentor, invited him to study with him in Tokyo, and put him to work classifying specimens at the Anthropology

Research Institute. Like many other young men in the Meiji era, Torii was gripped by “city fever” (

tokainetsu

) and mesmerized by Tokyo, spending his days exploring bohemian bookshops and teahouses, writing poetry, and studying German.

13

When not attending lectures, he pored over the precious English-language anthropology texts—E. B. Tylor’s

Primitive Culture

, Sir John Evans’s

The Ancient Stone Implements, Weapons, and Ornaments of Great Britain

—kept in the library’s protective glass case.

In order to establish the journal’s reputation as a center for modern research, Tsuboi included an English-language table of contents and discouraged breezy meditations from office-bound academics by stipulating that he would accept only articles based on “direct field observations.”

14

Every issue

included tales of expeditions from the northernmost reaches of Siberia to the distant islands of the South Pacific. Tsuboi needed a steady supply of intrepid explorers, and Torii was eager to oblige. Torii became the Japanese Indiana Jones, chronicling his adventures in bestselling books. Like Tsuboi, Torii was a true cosmopolitan. He studied the Incas in South America, and his books were translated

into French and awarded the Ordre des Palmes Académiques. He was among the first anthropologists to use photography in his ethnography, often illustrating his pieces with photographs of “exotic natives,” in which he himself occasionally appeared.

Studying with Tsuboi, Torii resurrected his fascination with race. “From the point of view of civilization and human solidarity, they are in an unhappy

state that merits our pity,” he wrote about Taiwan’s indigenous people. “But for the anthropologist, they constitute a marvelous field of studies. To what race of the human species do these populations belong?” Torii never missed an opportunity to embark on field trips, usually accompanied by his wife, Kimiko, an anthropologist who studied Mongolian history. He supplemented his university salary

with journalism assignments, which both paid well and made him famous. Both literally and metaphorically, Torii’s career tracked the course of Japanese colonialism, with the explorer often arriving soon after Japan’s troops. Japan had just won the Sino-Japanese War when he arrived in China in 1895. In 1905 he went to Manchuria and Mongolia, conducting research in the areas where Japan had only

months before defeated the Russian army. He made his first trip to Korea in 1911, and to Siberia in 1919, shortly after both territories were occupied by the Japanese.

Ryuzo Torii, 1896

(© University Museum, University of Tokyo)

The argument about Japan’s origins fell into two camps. The first held that the Japanese were a homogeneous people who had lived, relatively unchanged, in the same place for millennia. The other argued that the Japanese were a hybrid people whose ancestors drew from Korea, China, and other parts of Asia, synthesizing the most advantageous

traits from each. The theories coexisted, each dominating different periods of Japanese history, depending on the political situation. When Meiji leaders were first fashioning an ideology to keep citizens obedient to the emperor, the notion of Japan as a homogeneous nation came to the fore. As the empire expanded across Asia, it made sense to characterize the Japanese as a collection of different

Asian peoples.

15

Torii’s voice was the most influential in the hybrid camp. He argued that the Japanese synthesized the best characteristics of indigenous cultures from Manchuria, Korea, Indochina, and Indonesia. In addition to archaeological evidence, he cited the existence of contemporary Japanese people who possessed continental faces, southern features, and curly hair. Torii labeled the Stone

Age group who synthesized this multicultural brew the “Japanese proper,” a hybrid people who arrived in Japan after the Ainu, bringing sophisticated practices such as pottery, metallurgy, and monument building.

16

Korea played a large part in this project, as it did in Torii’s career. “I have a particularly close relationship to Korea,” he wrote. “Korea has become the center of economic, cultural

and material trade between the Asian continent and Japan, which should be happily welcomed.” Torii called Korea Japan’s “mythical and beloved ancient motherland,” which was why he favored uniting them in the modern era. “Korea is just like any other region of Japan such as the Kyoto-Osaka-Kobe region or Kyushu,” he wrote in a 1920 essay. Even if the two are not quite as close as brother and sister,

he adds, “Koreans and Japanese are equivalent to one’s parent’s cousins.” Torii cited studies that found affinities between the two countries’ language, material culture, religion, and customs. “Koreans are not racially different from Japanese. They are the same group and thus must be included in the same category. This is an anthropological and linguistic truth that cannot be changed.”

17

The

dominant theory was that the Japanese were an amalgam of races that had traveled to the archipelago and formed a nation whose cultural achievements towered over everyone else’s. In other words, although Asians were racially similar, some nations, such as the Japanese, had advanced further than others. Whether this was because of their system of government or their cultural prowess wasn’t certain.

But as the Japanese Empire expanded and brought more races into the fold, the Japanese public turned to intellectuals such as Torii to explain how it was that the Japanese could colonize people with whom they shared so much.

In May 1980, Kaoru Hasuike received the first good news since he’d arrived in North Korea twenty-two months earlier. He was summoned to his minder’s office, where several of the officials who oversaw his education were waiting for him. The news? His girlfriend, Yukiko, with whom he had been abducted, was in North Korea after all. In fact, she was in the next room.

Would he like to see her? “Yes!” Kaoru replied, so quickly that he was embarrassed.

1

It turned out that the story about Yukiko being left behind in Japan had been a ruse designed to force Kaoru to cut all ties to Japan, leaving him with no choice but to accept his situation. In reality, she had been undergoing the same pedagogical routine: learning Korean, studying the regime’s ideology, wondering

whether she could survive in this strange country. Like much else in North Korea, their isolation had been staged. They had been living barely a mile apart and were overseen by the same minder, who shuttled back and forth between them. At the very least there was now

one

other person who could understand what the other was going through.