The Invitation-Only Zone (18 page)

Read The Invitation-Only Zone Online

Authors: Robert S. Boynton

Jenkins became something of an expert abductee-spotter. One day in 1986, he and Hitomi were shopping with Jerry Parrish, the American soldier who defected two years before Jenkins, and Siham Shrieteh, his Lebanese

wife. They spotted a Japanese couple. “Good afternoon. How are you?” the Japanese man greeted them, in perfect English. Siham had met the woman a few months earlier, when they were both in the hospital giving birth, and the woman confided in Siham that she and her husband had been kidnapped from Europe by a Japanese terrorist group. Having spent twenty years in the North, Jenkins was no longer

surprised that the regime would resort to such measures. “The rules of logic, order, and cause-and-effect ceased to apply. Things happened all the time that made no sense, and for which we were given no explanation,” he writes.

4

He notes that most of what the abductees did was little more than busywork. For instance, during her twenty-four years in captivity, Hitomi, a trained nurse, never worked.

So what, then,

was

the point of the abductions? I ask Jenkins. He perks up. “Everybody says they were abducted for language training, but that’s just silly,” he says. “Would you like to know the

real

reason?” he asks me, a sly smile coming over his face. As a way of answering, Jenkins tells me about a visit two North Korean cadres paid to his home in 1995. Such visits were unusual, so he was nervous.

He became more alarmed when the conversation turned to his daughters. “Thanks to the great benevolence of Kim Jong-il, we want to send them to the Pyongyang University of Foreign Studies,” they announced. For Jenkins, this was a mixed blessing. The college was indeed one of the most prestigious in North Korea. But it was also a feeder school for the country’s intelligence service. “That’s

when I knew they were planning to turn Brinda and Mika into spies,” he says. Jenkins’s fears weren’t entirely unfounded. Kim Hyon-hui, a North Korean terrorist who blew up a South Korean airliner in 1987, was trained there.

“Think about it,” Jenkins says. “They would be perfect raw material for North Korean spies because they looked nothing like someone would

expect

a North Korean spy to look.”

Indeed, while mixed-race children are common in South Korea and Japan, they are unheard of in the North. The abduction project, Jenkins explains, was actually a long-term breeding program. That was why most of the Japanese were abducted in pairs, usually a girlfriend and boyfriend out for a romantic evening. It was also why the North Koreans had no use for Hitomi Soga’s mother. “The North Koreans

wanted Japanese couples who could have children that they would then use as spies,” Jenkins says.

But what would the advantage be of using the children of Japanese abductees? After all, they were raised to believe they were North Korean, spoke only Korean, and had none of their parents’ familiarity with Japanese culture or language. Jenkins looks at me pityingly and replies, “Because if their

parents are Japanese, then their children will have one hundred percent Japanese DNA! That way, if they get caught spying in Japan, they could take a blood test and prove to the police that they were Japanese, and not North Korean. They’d be the

perfect spies

!”

5

Korean Air Flight 858 departed Baghdad’s Saddam International Airport at 11:30 p.m. on November 28, 1987. The Boeing 707 was filled with South Korean laborers returning to Seoul, with stops in Abu Dhabi and Bangkok, after months of working on construction projects throughout the Middle East. Also on the plane were the Korean consul general in Baghdad and his wife. Two

Japanese tourists, Shinichi and Mayumi Hachiya, a seventy-year-old father and his stunning twenty-five-year-old daughter, occupied seats 7B and 7C. They checked no luggage, placing their few packages in the overhead locker.

At 2:04 a.m., the pilot radioed Rangoon International Airport. “We expect to arrive in Bangkok on time. Time and location normal.” One minute later, as it passed from Burmese

to Thai airspace, the plane exploded, killing all 115 passengers and crew, brought down by a Panasonic radio packed with plastic explosives.

A quick check of the passenger list showed that the Japanese father and daughter had disembarked at Abu Dhabi, and on further inspection it was discovered that their passports were fake. In the meantime, the Hachiyas had flown on to Bahrain, where they were

awaiting a flight to Rome. The Bahraini police detained them and escorted them to security for questioning. Before entering the office, Mr. Hachiya asked permission for him and his daughter to have a smoke. Immediately after putting the cigarette to his lips, he collapsed and died. Seeing this, a quick-witted police woman knocked Mayumi’s cigarette from her mouth and wrestled her to the ground.

The cigarettes were laced with cyanide, but Mayumi’s only caused her to lose consciousness. “The pitch blackness enveloped me like a comforting blanket.

Everything was over

,” she recalled.

1

Mayumi awoke in a Bahrain hospital, the inside of her mouth covered with blisters from the poison. She insisted she had had nothing to do with the bombing and was interrogated for two weeks before being taken

to South Korea, where the questioning continued. One afternoon, the interrogators took her on a drive through downtown Seoul. “There was a flood of automobiles. Not even in Western Europe had I seen so many cars, jostling in the broad streets. Shocked, I studied the drivers. They were Koreans, not foreigners,” she recalled. “The spectacle was so different from what I had expected that I didn’t

know what to say.” She confessed the next day. “Forgive me, I am sorry. I will tell you everything,” she said.

Her name was Kim Hyon-hui, and she and her “father” were North Korean agents. The bombing was a direct order from Kim Jong-il, intended to discourage people from attending the upcoming Seoul Olympics. It is only a slight exaggeration to say that Kim Hyon-hui had been training for this

mission all her life. At sixteen, she was singled out for her intelligence and beauty, and given special language training. At eighteen, she entered espionage school, where she underwent seven years of grueling training, mastering martial arts, knife combat, shooting, swimming, and code breaking. In one exercise, she infiltrated a mock embassy, cracked the safe, and memorized the message it held.

She beat the guards unconscious, for good measure.

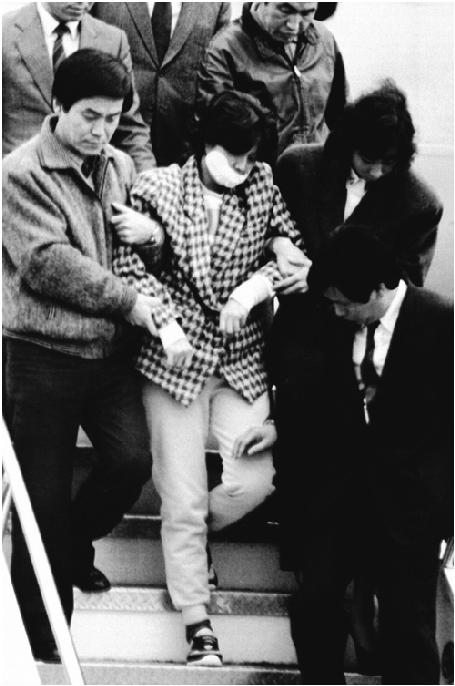

The terrorist Kim Hyon-hui being taken off a plane in South Korea

(Associated Press)

Her linguistic training was similarly thorough. After attending the Pyongyang University of Foreign Studies, she received Japanese lessons from a woman who had been abducted from Japan in June 1978. They became close friends, and the Japanese tutor told her about the children she’d left behind. One day, the

tutor asked to see how ordinary North Koreans lived, and the next afternoon they snuck out of the military college to visit a nearby village. “We found a decrepit cluster of houses and filthy children running around the streets, some naked. I was ashamed at this and tried to pull [her] away. But she stared at the children with tears in her eyes,” recalls Kim. “‘So

this

is your brave new world?’

she asked. ‘I pity you.’” The description of the tutor matched that of a twenty-two-year-old bar hostess and mother of two who had disappeared from Tokyo in 1978. For the first time, the Japanese government had direct evidence of the abductions.

* * *

“She is even more gorgeous in person than in her photograph,” Hitoshi Tanaka, the Japanese Foreign Ministry’s director for Northeast Asian

affairs, thought to himself. The man in charge of Japan’s relations with the Korean Peninsula, Tanaka was the first Japanese official to meet Kim Hyon-hui. The United States was pushing Japan to impose sanctions on North Korea immediately after the bombing, but Tanaka wanted to be sure that the crime had in fact been committed by North Korea. South Korean intelligence had manufactured cases against

the North in the past, and the Americans were being too pushy for his taste. If nothing else, Tanaka wanted to show them that Japan was an independent state, with its own foreign policy.

South Korean intelligence, fearing the North would assassinate Kim, had secured her at a safe house deep in the mountains. Tanaka’s car climbed up the twisting, remote roads for several hours. “I went to meet

her, to see her with my own eyes, and understand who she was,” he says.

2

For a woman who had just murdered more than a hundred people, she possessed an otherworldly calm he found unsettling. “You’ve traveled the world and can see through the lies North Korea tells its people. How could you have done such a thing? Didn’t you hesitate when you realized all the innocent people you’d kill?” he asked.

Her response said as much about her as the regime that had produced her. She admitted she had traveled through the West but claimed she had been told what she saw there was an illusion. “I was taught that it was superficial, and designed to hide the awful capitalist reality that lurked behind it,” she said without emotion. It was astounding to behold someone convinced she was floating through

a fictional world. She reminded Tanaka of a plastic flower: beautiful but lifeless.

3

Having sent her husband and four children off for the day, Kayoko Arimoto was enjoying a restorative cup of tea when the telephone rang. It was just after ten on a late September morning in 1988. She didn’t recognize the voice on the line, and nearly dropped the phone when she heard whom the woman was looking for. “Is this Miss Keiko Arimoto’s residence?” the woman asked.

1

In April 1982, Kayoko’s daughter, Keiko, had moved to London to study English. Keiko’s parents hadn’t liked the idea of her going so far away, but they gave their permission, on the condition that she return home the next year. She agreed, but as soon as she got to London, she began looking for a job. In March 1983 the Arimotos received a brief letter from Keiko: “I will be home later than the

original schedule because I found a job here. I am not going to stay in one place, as this is marketing research. I’ll write to you from wherever I go.” They never heard from her again.

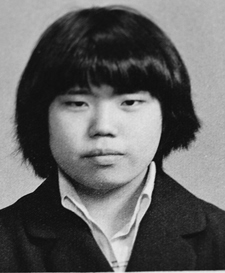

Keiko Arimoto

(Asger Rojle Christensen)

The caller that September morning in 1988 explained that she was in a similar position. Her son, Toru Ishioka, had disappeared while traveling through Spain eight years before, and she had just received a letter from him, in which he asked her to contact Keiko’s family. “I can’t be more explicit, but during our travels in Europe we ended up here in North

Korea,” the letter began. He and Keiko were living in Pyongyang with another Japanese man. “We basically support ourselves here, but we do receive a small daily stipend for living expenses from the North Korean government. However, the economy is bad, and I have to say it is a hardship to be living here for so long. It’s especially difficult to get clothes and educational books, and the three of

us are having a hard time. Anyway, I wanted to at least let you know that we are all right, and I am going to entrust this letter to a foreign visitor.”

Written on a single piece of paper, the letter had been folded down to the size of a postage stamp. On the back was written, “Please send this letter to Japan (our address is in this letter).” The envelope bore a Polish postmark and stamp, and

had presumably been mailed by a Polish tourist. In it were two photographs: one of Toru, Keiko, and a baby; and the other of an unidentified Asian man. Keiko looked thin, her normally plump face sallow. Still, Kayoko was grateful to receive news that her daughter was alive. But how had Keiko gotten to North Korea? And who, she wondered, was that baby?