The Invitation-Only Zone (13 page)

Read The Invitation-Only Zone Online

Authors: Robert S. Boynton

Their boat departed Niigata on June 18, 1963, carrying thirteen hundred people, the largest number in the repatriation project so far. There were several other Japanese wives on board, and

Hiroko remembers that they, too, looked nervous.

* * *

Precisely why Kim Il-sung invited Japan’s Koreans to move to North Korea is still the subject of active debate. With all the challenges it faced in the wake of the Korean War, why would North Korea want such an enormous infusion of people? Was it a humanitarian act toward fellow Koreans? A pragmatic bid to alleviate a domestic labor

shortage? Scholars have cast doubt on these explanations. North Korea’s Five-Year Plan, released three months before the repatriation began, stated clearly that no increase in immigration was planned. “People who went to North Korea thinking they would work and contribute found that they didn’t have much to do,” says Park Jung-jin, a Seoul National University historian.

7

He argues that North Korea

used the flow of people as a diplomatic tool. “The repatriation took place at precisely the moment when Japan and South Korea were making great advances in their normalization negotiations,” he tells me. The spectacle of thousands of ethnic Koreans rejecting capitalist Japan and heading to the socialist North would throw a wrench into the process. Judging by the fact that Japan–South Korea normalization

talks didn’t come to fruition until 1965, Kim Il-sung’s intervention may have been successful. Since the majority of the Koreans in Japan originally came from the southern part of the peninsula, the repatriation was no small embarrassment for South Korea. In fact, South Korea was so incensed that it threatened to sink the ships sailing to North Korea from Japan.

In the end, North Korea probably

had a variety of motivations for receiving the repatriates. But whether the ninety-three thousand returnees were victims of Japanese prejudice, beneficiaries of North Korean ethnic solidarity, or some combination of the two, they were surely also pawns in a tragic Cold War skirmish they knew nothing about.

* * *

Like Katsumi Sato, Harunori Kojima descended from a long line of poor Niigata

rice farmers.

8

Born in 1931, Kojima, the second of nine children, grew up in Kameda, a village on the outskirts of Niigata. As a child he longed to take part in Japan’s glorious war, and at thirteen his dream came true. In 1944, with U.S. forces advancing toward the home islands, Japan’s fighter planes were outpaced by the improved U.S. models. If they couldn’t hold their own in combat, perhaps

they would be more effective as manually guided missiles?

Kamikaze

(“divine wind”) is a historical reference to the gales that destroyed the Mongols when they tried to invade Japan in 1274. As the winds protected Japan then, the new kamikaze would protect it now. The first kamikaze attack occurred in October 1944, and it was a successful strategy at first. More than 2,000 planes made such attacks

in the months that followed, but the death of 2,530 pilots had little impact on the course of the war.

Kojima arrived at training camp in July 1945, thrilled by the opportunity to take on the Americans, even though he knew it would cost him his life. With few functional planes available, the students were trained on ancient aircraft, some twenty years old. Because it was too dangerous to use

real explosives, the planes were fitted with dirt-filled rice barrels to simulate the deadly payload. Miraculously, one month into Kojima’s training, Japan surrendered. Although devastated by the loss, he was relieved to be alive. But what had all the young men of his generation died for? he wondered. He passed through Tokyo on the long slog back to Niigata and was shocked to discover that the city

had been destroyed, block after block burned to the ground by incendiary bombs. This was what came from a nation geared toward war, he thought. “I understood then that Japan couldn’t be rebuilt by militarists. For that we needed an egalitarian, socialist state,” he says.

It seemed to Kojima that everyone he knew in Niigata had come to a similar conclusion. He was impressed by the principled pacifism

of the Communists who were released after long jail sentences, and he noted their growing presence in the legislature. Even his uneducated, rice-farming family had joined a leftist agricultural union. Kojima joined the Communist Party in 1950 and was assigned to the publishing division. He marched in Niigata’s raucous May Day parade and applauded when Khrushchev denounced capitalism on his

1959 trip to America. And it wasn’t only the Japanese who were awakening to the miracle of socialism. “It seemed like all of Asia was taking up this philosophy,” he says. “Why should we wait a day longer than we had to in order to reduce the terrible inequality of wealth in Japan?” One day, he stumbled on a copy of Edgar Snow’s

Red Star over China

(1937), an admiring account of the author’s time

with Mao and his Red Army guerrillas. Kojima was intoxicated. “I saw the beauty and majesty of the Chinese experiment,” he says. “We watched the flames of revolution spread across Asia and create the nation of North Korea.”

Such was the ideological tenor of the Japanese who participated in the repatriation project. China seemed well on its way to success, but North Korea, devastated by the Korean

War, needed help from its comrades. To support himself, Kojima ran a leftist bookstore two doors down from the cosmetics shop that Katsumi Sato and his wife ran. Sons of rice farmers and now fellow members of the Communist Party, Sato and Kojima met in 1955. “I trusted him deeply. We understood each other completely,” says Kojima. From 1960 to 1964 they worked in the same downtown office building,

Kojima for the Repatriation Cooperative Association, and Sato as secretary-general of Niigata’s Japan–North Korea Friendship Association. Sato’s job was to nurture the relationship between North Korea and the Japanese Communist Party, which he did so well that he was twice awarded North Korea’s Medal of Honor. He had never known many Koreans, and he loved their passion and directness. “Their

simplicity was magnificent. They didn’t hide themselves: whatever they are, they’ll show you,” he says. While Sato cultivated the political alliance, Kojima took care of the repatriation project’s day-to-day business. Families typically stayed in Niigata for three days before embarking, and he made sure their paperwork was in order. He noticed that Chosen Soren officials were always on hand to help

the repatriates unburden themselves of possessions that were too large to take along.

The first of the Koreans to go were the poorest of the poor, the destitute who had nothing to keep them in Japan. Sato was surprised by how many of the men were missing fingers and limbs. It turned out that the Chosen Soren had, in good egalitarian fashion, given priority to those who’d worked dangerous wartime

jobs in mines and factories. He was pleased that these unlucky souls were finally being treated like human beings. “This is what communism is all about!” he thought to himself. There were times when it felt like a big party. “I had never seen anyone so happy,” says Kojima.

9

“They were smiling so much it looked like their faces were about to rip apart.” Every night, the Korean repatriates and Japanese

Communists would dance, and sing Korean folk songs.

Sato became particularly close to the head of Niigata’s Chosen Soren branch and still gets emotional when he describes their last encounter, before the latter left for North Korea. “I said, ‘Send me a letter when you get there so I know you are all right,’” says Sato. A few months passed, then a year, but Sato heard nothing. He asked colleagues

if they had heard any news of his friend, but they had not. Finally, two years later, a letter arrived. The stock used for international letters was typically very thin, but the paper Sato’s friend had used practically fell apart in his hands. “You wouldn’t have used it for toilet paper, and all he had written on this miserable scrap of paper were praises for the Dear Leader, Kim Il-sung.” The

letter concluded with a request: “Please send me some pepper, seasonings, pens, writing paper, and a warm jacket.”

More letters from repatriates arrived. The news was uniformly positive: life was wonderful, education and health care were free—all due to the generosity of Kim Il-sung. But they inevitably included requests for the most basic clothing, medicine, and food items, the kinds of things

that even the poorest in Japan took for granted. Around 1961 the repatriates began using code to communicate their true feelings. The Japanese language, exquisitely sensitive to class distinctions, stipulates different grammatical constructions depending on the recipient. A letter from a close relative written in a style reserved for official communications sent a clear message: “Don’t come.” Other

codes were based on the use of pencil or pen; if a letter was written in pen, it meant “You can believe what I have written,” but if it was in pencil, that would indicate the opposite.

10

Other letters were more circumspect. As an addendum to the good news and praise for Kim Il-sung, they’d suggest their relatives join them—or so it seemed. In one, an uncle advised his nephew not to come until

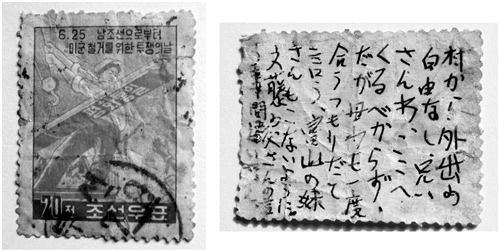

his twentieth birthday. The boy in question was a newborn, says Sato. In other cases, messages describing the abysmal living conditions were hidden on the back of the stamp.

Stamp with secret messages sent from North Korea: “We cannot leave the village. Older brother, do not come. Mother says she wishes to see you. Tell our sister in Toyama also not to come. What Bunto’s father said is correct.”

(Courtesy of Kimikatsu Kinoshita)

The recipients were reluctant to discuss what they were learning, for fear that news of their discontent might reach North Korea, where

it might endanger their families. Others held on to the chance that these were simply the complaints of a few ideologically suspect malcontents, as Chosen Soren officials assured them. Regardless of the veracity of the reports, nobody wanted to sully the reputation of the new socialist state.

In July 1964, Kojima was finally given permission to visit North Korea and see the promised land to which

he had been sending people for the last five years. Despite the rumors, he was still a true believer in the Communist project and had made several requests to visit. Then, like now, North Korea was extremely secretive, and the only people who traveled back and forth between Japan and the North were government officials. Kojima visited all the important destinations: Pyongyang, Unsan, Kanko, Nampo,

the demilitarized zone (DMZ) at the Thirty-Eighth Parallel. Conditions were more primitive than he had anticipated, but he chalked this up to the sanctions imposed by Western imperialists. More troubling was how closely his hosts monitored his group. Here they were, comrades in arms, watched over as if they were spies. They couldn’t interact freely with North Koreans, and the people they did

meet were too scared to say anything of substance. In fact, their responses felt rehearsed, invariably ending with some version of the phrase “due to the magnificent glory of Kim Il-sung.” Kojima was especially eager to meet some of the repatriates he had helped emigrate, but he was told they were too busy working.

Like many other Japanese tourists at the time, Kojima was crazy about cameras

and had brought two with him. One was a still camera, and the other was one of the new 8 mm video cameras whose sales were helping fuel Japan’s postwar economic boom. Frustrated by how little he learned by talking to people, he vowed to take pictures of everything he saw. Kojima’s enthusiasm made his government minders uneasy, and again and again they asked him to put his cameras away. At Unsan, he

photographed a line of women walking down the road with baskets balanced on their heads in traditional fashion. His minder was aghast. “These are not the kind of photos you should take of North Korea,” he said. A shot of a group of shirtless boys playing soccer in a village square was judged similarly inappropriate. Finally, they instructed him not to include

any

people in his photographs. Security

officials went through Kojima’s photos before he boarded his plane to Beijing, destroying any they deemed offensive. Fortunately, the 8 mm video camera was new enough that the North Koreans didn’t have the technology to examine his footage.

Kojima was upset when he returned to Niigata. A condition of the trip was that he make several presentations describing the wonders of the socialist paradise.

This posed a dilemma. How to avoid mentioning the disturbing aspects of the visit? He decided simply to describe what he had seen: new hospitals, schools, apartments, roads, and other products of a bustling nation. About the things he hadn’t encountered—freedom to speak, freedom to inquire, freedom in general—he kept silent. “I was still working in the offices of the repatriation project, so

I tried to rationalize it. I’d spent so many years as a Communist that telling the whole truth would have required me to reject everything I believed,” says Kojima. There was only one person with whom he could share his doubts. A week after he returned, Kojima invited Sato to his house one evening to view the videos he’d made. “We started watching at about ten o’clock in the evening, and kept going

until the sun came up. We’d watch the film through, again and again, stopping to discuss what we’d seen. Analyzing, arguing, wondering what it all meant,” says Sato.