The Intimate Sex Lives of Famous People (52 page)

Read The Intimate Sex Lives of Famous People Online

Authors: Irving Wallace,Amy Wallace,David Wallechinsky,Sylvia Wallace

Tags: #Health & Fitness, #Psychology, #Popular Culture, #General, #Sexuality, #Human Sexuality, #Biography & Autobiography, #Rich & Famous, #Social Science

In her first singing job she refused to pick up customers’ tips from the table in the customary manner—using her vaginal lips—and the other girls started calling her “Lady.” Yet she wore no underwear onstage, and one night

she expressed her sentiments to an unappreciative audience by raising her skirts as she stalked off.

“Lady Day” could really sing the blues with passion, and the men she chose to sleep with gave her violent inspiration. She liked them big and pretty. Of one drummer she remarked: “They don’t call him ‘Big Sid’ because he’s six foot three, you know.” In her 20s she had many musician-lovers and often sang with her pretty face marred by black eyes and her body covered with bruises. If her friends warned her away from a bad character, she usually went after him with more determination than ever. Men used her and spent her money; before long she had a reputation as an easy mark.

LOVE LIFE:

The dates of various events in Billie’s life are cloudy; for example, that of her engagement to a young pianist named Sonny White. Their relationship was no rougher than most of Billie’s casual affairs, but both of them supported their mothers and eventually the problems involved ended the romance.

Tenor sax player Lester Young was the best friend Billie ever had. His obbligato solos matched Billie’s moods so perfectly that the records they made together are considered her finest. Lester shortened her last name and called her “Lady Day”; she affectionately called him “Pres,” short for “President Roosevelt.” It is interesting that through all their years together—recording, on the road, nightclubbing—their friendship was never physical. The music they made together shows that Lester touched Billie as no other man could, and years later, when they had parted ways, an old Lester told a writer, “She’s still my ‘Lady Day.”’

In 1941 Billie met her husband-to-be, handsome businessman Jimmy Monroe. Jimmy “smoked something strange.” When their marriage began to founder, she thought that joining Jimmy in his opium smoking would restore the lost magic, but before she was 30 she was separated from him and living with trumpeter Joe Guy, then 25 years old. That relationship was a triangle— Joe, Billie, and her heroin.

Drug busts and touring eventually separated them, and Billie’s next choice of a lover, John Levy, proved a disaster. Levy managed a nightclub and gave her a singing job when nobody else would. He bought her nice clothes, gave her wholesale jewelry, and gradually took over her finances. Although she was making $3,500 a week, she had to beg him for pocket money. Levy eventually left Billie and her band stranded and broke during a tour in the South.

The year 1956 brought a second marriage for Billie, to Louis McKay, a club owner and her manager. She was devoted to Louis, but they filed for divorce in California in late 1958. “Lady Day” died before the divorce decree was finalized.

—J.M.

The Virtuoso

The Virtuoso

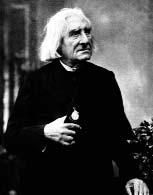

FRANZ LISZT (Oct. 22, 1811–July 31, 1886)

HIS FAME:

Renowned as the foremost

piano virtuoso of his era, Liszt revolutionized

the piano recital genre and spent a lifetime

promoting the musical arts in Europe.

HIS PERSON:

The son of a Hungarian

nobleman’s servant, Liszt was a child prodigy. The European aristocracy, for whom he

would spend his life playing, was impressed

by the boy’s talents and financed his musical education. Acknowledged as the greatest

pianist of the day, he led an exciting life

traveling from Portugal to Turkey to Russia,

and achieved widespread fame in the

process. In 1848, at the peak of his career,

he accepted the directorship of the Weimar

court theater. During the next 13 years he instilled new life into European music, not only with his concerts and operatic productions but also through his encouragement of such new composers as Richard Wagner. After leaving Weimar, Liszt spent eight years living and working in Rome, where he became an abbé of the Roman Catholic Church. (This entitled him to perform the rite of exorcism.) The next 17 years he spent playing, teaching, and directing in Rome, Weimar, and Budapest. Liszt’s genius brought him such great wealth that midway in his career he ceased to work for money, devoting his efforts instead to fund-raising for worthy causes. In his waning years, the rigors of traveling for these charitable enterprises weakened him, and in 1886 he died of pneumonia in Bayreuth, Germany.

Throughout his career, Liszt demanded respect from his aristocratic audiences and constantly sought to elevate the status of artist above that of superservant. On one occasion he refused to play for Isabella II after he was denied a personal introduction to her majesty because of Spanish court etiquette. Another time he halted a performance in mid-flight and, with head bowed and fingers poised above the keyboard, waited until Czar Nicholas I of Russia ceased speaking. Despite these flashes of hauteur, his passionate style ensured his popularity. Striding forcefully to the stage, his long mane of whitening hair flowing behind him, he would tear off his doeskin gloves and toss them dramatically to the floor, seat himself as he flipped back his coattails, and address the keyboard with lips pressed and eyes blazing.

LOVE LIFE:

Like the rock stars of today, Liszt was smothered with feminine adulation. His appearances caused a sensation as his female admirers sought sou-262 /

Intimate Sex Lives

venirs; one lady even stripped the cover from a chair that had held the revered posterior. Lovers were his for the taking, and he had dozens, especially among the noblewomen who made up his audiences and pupils.

Crushed at 17 when he was forced to break off a budding romance with Caroline di Saint-Crieg, one of his aristocratic piano pupils, Liszt withdrew into a period of fierce practice that yielded the extraordinary skills that were to bring him society’s adoration. His earliest substantial liaison was with the Countess Adèle de la Prunarede, but he broke off the affair upon learning that the countess had a second lover. Liszt’s first longterm relationship began in 1835, when Countess Marie d’Agoult left her husband and children in Paris to join Liszt in Switzerland, where she bore him three children. (Their daughter Cosima later became Richard Wagner’s wife.) In 1839, however, the couple separated, their relationship strained by Liszt’s loss of interest and his friendship with Frédéric Chopin’s mistress George Sand, a cigar-smoking writer of risqué novels who loved to sit under the piano while Liszt played. When the countess challenged Sand to a duel at one point—the chosen weapon was fingernails—Liszt locked himself in a closet until the ladies calmed down.

Liszt’s name was soon linked with that of Lola Montez, a hot-blooded and beautiful-bodied Spanish dancer who had achieved notoriety by baring her breasts when introduced to King Ludwig I of Bavaria. When Liszt tired of their stormy affair, he deserted Montez while she was napping in a hotel room and left money to pay for the furniture he knew she would destroy in her rage. Liszt’s sexual peccadilloes were the talk of European musical society. His mistresses included the eccentric Italian-born Princess Christine Belgiojoso, who once had the body of a deceased lover mummified and kept it at home in a cupboard; the Russian Baroness Olga von Meyendorff, known as the “Black Cat” because of her tight-fitting black clothing; the young Polish Countess Olga Janina, who threatened to shoot and poison Liszt when he broke off their relationship; and the famous courtesan Marie Duplessis, who inspired

Camille

.

The longest affair of Liszt’s life, extending through his Weimar and Roman periods, was with Princess Carolyne von Sayn-Wittgenstein. This intellectual Polish noblewoman left her Russian husband and her feudal estates to join Liszt in Weimar, where she spent hours lying on a bearskin rug wearing a turban and smoking a hookah while Liszt played the piano. Liszt hoped to marry the princess and went to Rome to seek papal approval for her divorce, an approval thwarted by her Russian husband’s influential connections. By this time Liszt’s feelings toward Carolyne had begun to cool, and he was relieved that the divorce was denied.

Liszt’s sexual exploits continued into his autumn years, and he was frequently involved with a pupil young enough to be his granddaughter. He claimed, however, that because of his reverence for virginity he had never

“seduced a maiden.” Even though he feared impotence—and used a variety of stimulants to prevent its onset—he had a longer list of lovers than almost any of his contemporaries. Liszt’s only comment was, “I didn’t take a big enough bite of the apple.”

—J.Z.

Warmhearted Wunderkind

Warmhearted Wunderkind

WOLFGANG AMADEUS MOZART (Jan. 27, 1756–Dec. 5, 1791)

HIS FAME:

Considered the purest

example of “raw genius” in history,

Mozart was the greatest musical technician of all time and one of the world’s

supreme creative artists. Master of all

forms, he composed over 600 works,

including choral and chamber works,

symphonies, sonatas, concertos, and

operas. Critics call his

Don Giovanni

and

The Marriage of Figaro

the most perfect

operas ever written.

HIS PERSON:

This most prodigious of

all child prodigies, born in Salzburg,

Austria, began music lessons at four with

his violinist father, Leopold, a stern but

loving disciplinarian. Composing from the age of five, Mozart at six astonished the royalty of Europe as he and his gifted sister made the first of many arduous concert tours. A virtuoso on violin, organ, and harpsichord, he was called

“

Wunderkind

” (“marvelous child”) and showered with attention. Yet he remained completely natural and affectionate.

His adult life was a sharp contrast to his younger years. Short, pale, insignificant in appearance, he could not command the interest of aristocratic and ecclesiastical patrons as a serious and mature composer. He never found an official post that paid enough to enable him to devote himself fully to the major works he longed to write. Precious time was wasted giving perfunctory lessons and grinding out charming potboilers. His life was a long losing struggle against jealous rivals, illness, and poverty. He and his wife, Constanze, did not live within their financial means. Pleasure-loving, they were unable to keep money from vanishing, not the least because of their generous handouts to every comer.

Mozart died at 35 of kidney disease brought on by overwork and malnutri-tion. He was in debt to his tailor, the druggist, the upholsterer, as well as his friends. Working feverishly, he tried unsuccessfully to finish his great

Requiem

before his own funeral. A heavy rainstorm prevented his wife and friends from accompanying the coffin to the graveyard. Not until 17 years later did Constanze realize that Mozart’s remains had been dumped into an unmarked pauper’s grave.

LOVE LIFE:

Pampered by women as a child, he was precociously aware of their looks. He once wrote his father, “Nature speaks as loudly in me as in any man, perhaps more forcefully than in many a big strong oaf.” Mozart enjoyed flirting, saying that if he had had to marry every girl with whom he flirted, he would have been a husband 100 times. At 21 he carried on a playfully indecent correspondence—full of double meanings—with his favorite cousin, Maria Anna Thekla Mozart.

While on tour Mozart stayed with the musical Weber family of Mannheim and seriously lost his heart for the first time. The object of his affections was Aloysia Weber, 16, a lovely girl who was studying to be an opera singer. Encouraged by her designing mother, she flirted with Mozart, who was enchanted. They played and sang together by the hour. Wolfgang’s father heard about it and ordered him summarily back on his tour since he thought the “loose-living” Weber clan was socially beneath the Mozarts. Some months later Wolfgang returned to Mannheim to find that Aloysia, now ensconced as a member of the Munich opera, had forgotten him. Their meeting was so awkward that Mozart sat down at the piano and played a ribald song to cover his hurt feelings. Long after Mozart’s death, when Aloysia was asked why the relationship had cooled, she replied, “I did not know, you see. I only thought he was such a

little

man.”