The Intimate Sex Lives of Famous People (47 page)

Read The Intimate Sex Lives of Famous People Online

Authors: Irving Wallace,Amy Wallace,David Wallechinsky,Sylvia Wallace

Tags: #Health & Fitness, #Psychology, #Popular Culture, #General, #Sexuality, #Human Sexuality, #Biography & Autobiography, #Rich & Famous, #Social Science

Ah, how in there I am so tight.

Coax me to come forth to the summit:

so as to fling into your soft night,

with the soaring of a womb-dazzling rocket,

more feeling than I am quite.

—R.J.R.

The Whippingham Papers

The Whippingham Papers

ALGERNON CHARLES SWINBURNE (Apr. 5, 1837–Apr. 10, 1909)

HIS FAME:

An innovative writer of

the Victorian era, he gained fame with

the poetic drama

Atalanta in Calydon

(1865) and notoriety with the sensual

lyrics in

Poems and Ballads

(1866).

Later he produced several volumes of

literary criticism.

HIS PERSON:

Born of noble ancestry

in London, the eldest child of a naval

captain, Swinburne cut an odd-looking

figure. He had a puny physique, an

oversized head covered with carrot—

colored hair set atop severely sloping

shoulders, and a springy gait. His high-pitched voice turned into a falsetto

during times of excitement, and a nervous constitution produced an effeminate manner, trembling hands, and cataleptic fits. Yet his ambition was to be a soldier, until his father prudently scotched the idea. In 1861 Richard Monckton Milnes introduced Swinburne to the writings of the Marquis de Sade, whom he emulated thereafter. He lived for a time with artist Dante Gabriel Rossetti and befriended a number of homosexuals and unusual types. His first success,

Atalanta

, was followed by volumes of poetry generally criticized for their obscene content. Heavy drinking and carousing so undermined the poet’s fragile constitution that in 1879 he lay near death. At that time he was “adopted” by Walter Theodore Watts (later Watts-Dunton). Watts-Dunton was a critic, poet, and novelist whose works include

The Coming of Love and

Aylwin

. Swinburne was nursed back to health at the Pines, Watts-Dunton’s estate, where he resided until his death 30 years later. During that time he produced numerous volumes of poetry and criticism. Although Watts-Dunton clearly saved the dissolute poet from an early grave, some critics charge that his incessant mothering smothered Swinburne’s genius.

SEX LIFE:

Swinburne was a masochist who acquired a taste for flagellation at Eton’s infamous flogging block. He once rinsed his face with cologne just before a whipping in order to heighten his senses. He later was a regular customer at a flagellation brothel in the St. John’s Wood section of London.

Euphemistically referred to as the “Grove of the Evangelist,” the house featured rouged blond girls who whipped to order while an elderly lady collected

clients’ fees. Swinburne observed, “One of the great charms of birching lies in the sentiment that the floggee is the powerless victim of the furious rage of a beautiful woman.”

He shared his love for the lash with his cousin Mary Gordon, but there is no evidence that they did anything more than talk about it. Swinburne may have proposed to Mary, and he reportedly was crushed at the announcement of her marriage to another. Later she denied that they had ever been lovers.

Swinburne was positively obsessed with flogging. It dominated his whole life, his every fantasy, and a great deal of his writing. His widely published poems were shocking enough to earn him insults, full as they were of heterosexual sadomasochistic fantasy and references to death, delirium, and hot kisses.

Punch

magazine called him “Swine Born”; one literary critic accused him of “groveling down among the shameless abominations which inspire him with frenzied delight”; and Thomas Carlyle described him as “standing up to his neck in a cesspool, and adding to its contents.”

But his unpublished and underground works would have been the real shockers to the critics, had they read them. They bore such titles as

The Flogging-Block

,

Charlie Collingwood’s Flogging

, and

The Whippingham Papers

. Some of these writings appeared anonymously in

The Pearl

, an underground journal of Victorian erotica.

Swinburne, wistfully pining after the glorious Eton beatings, once wrote in a letter to his homosexual poet friend George Powell, who was at the college: “I should like to see two things there again, the river—and the block.”

He asked for news of Eton whippings: “the topic is always most tenderly interesting—with an interest, I may say, based upon a common bottom of sympathy.” Powell sent him a special present: a used birch rod. Swinburne was delighted and wrote that he only wished he could be present at an Eton birching. “To assist unseen at the holy ceremony … I would give

any

of my poems.” Powell next sent him a photograph of the flogging block. Swinburne was happy but wished for an action picture. “I would give anything for a good photograph taken at the right minute—say the tenth cut or so.” An 1863 letter to his friend Milnes finds Swinburne irritated that Milnes would stoop to flogging a boy of the lower classes. Birching, he chastised, was an aristocratic sport.

There is no concrete proof that Swinburne was gay. However, besides his friendship with Powell, he was close to the homosexual painter Simeon Solomon, who sent him drawings depicting flagellation. Swinburne was once seen chasing Solomon around the poet Rossetti’s home while both were naked. And his letters imply homosexuality. At an Arts Club dinner Swinburne got drunk and professed a horror of sodomy, but wouldn’t stop talking about it. He appears to have been impotent with women. In an attempt to cure him of his bad habits, Rossetti once paid Adah Isaacs Menken, a popular entertainer and lover of the period, £10 to sleep with Swinburne. After several attempts she returned the fee, explaining that she had been “unable to get him up to scratch” and couldn’t “make him understand that biting’s no use!” Perhaps to refute rumors of his homosexuality, Swinburne boasted to friends of the “riotous concubinage” he had enjoyed with Adah. The nature of the relationship between Swinburne and his mentor Watts-Dunton remains unclear. In Swinburne’s last will, he named the poet his sole heir.

QUIRKS:

Flagellation was not Swinburne’s only quirk. He also was inordinately fond of babies, especially plump, cherubic ones. He loved to cuddle and caress them. He collected baby pictures and kept on his desk a figurine depicting a baby hatching from an egg. Although there are no grounds for believing that he ever sexually abused an infant, his close relationship with Bertie Mason, the five-year-old nephew of Watts-Dunton, so alarmed Mrs. Mason that she temporarily removed her son from the Pines. The lad’s absence inspired Swinburne’s book of poems

A Dark Month

.

An extraordinary account of Swinburne’s experiences with George Powell in a French cottage is given by the writer Guy de Maupassant, who visited them when he was 18. After lunch “gigantic portfolios of obscene photographs” were produced, all of men. Maupassant recalled one of an English soldier masturbating. At a second luncheon, Maupassant tried to decide if the two men were really homosexuals. His conclusion was that they had sex with their pet monkey and with clean-cut 14-year-old servant boys. The monkey, he further reported, had been hanged by one of the jealous servant boys.

Another young man claimed to have visited Swinburne when he was living in a tent on the Isle of Wight, again with a monkey, which he dressed in women’s clothes. Swinburne made advances toward the boy after expounding on “unisexual love.” At this, the jealous monkey attacked the visitor. Swinburne persuaded his young man to return for a second lunch. This time the main course was grilled monkey. Hearing these rumors, Oscar Wilde said that Swinburne was “a braggart in matters of vice, who had done everything he could to convince his fellow citizens of his homosexuality and bestiality, without being in the slightest degree a homosexual or a bestializer.”

HIS THOUGHTS:

Russian novelist Ivan Turgenev once asked Swinburne to name the most original and unrealizable thing he would like to do. “To ravish St. Geneviève,” the poet replied, “during her most ardent ecstasy of prayer—

but in addition, with her secret consent!”

—W.A.D. and A.W.

The Sexual Vagabond

The Sexual Vagabond

PAUL VERLAINE (Mar. 30, 1844–Jan. 8, 1896)

HIS FAME:

One of the great French

writers of the 19th century, Verlaine

expanded the rhythmic and harmonic

frontiers of French poetry. He was also

well known for his bohemian way of life

and bisexual love affairs, including one

with the poet Rimbaud.

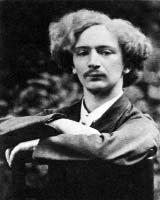

HIS PERSON:

His father was an army

officer who amassed a comfortable nest

egg, his mother a simple woman who kept

the fetuses of her three stillborn infants in

glass jars and jealously indulged her only

surviving child. Throughout his life Verlaine would remain his mother’s beloved

Verlaine at age 49

son, weak and irresponsible, demanding

yet submissive, sexually ambivalent.

He was “overcome by sensuality” at the age of 12 or 13, Verlaine remembered, but his personal slovenliness and ugliness aroused antipathy rather than attraction. His face was broad and flat with narrow slanting eyes set under thick brows. Children taunted him, and a teacher said he looked like a degenerate criminal.

At school he was attracted to younger boys, with whom he formed “ardent”

friendships. One of them, Lucien Viotti, has been described as a pretty youth with “an exquisitely proportioned body.” At about the age of 17 Verlaine became a regular patron of female prostitutes, exploring with great relish the borders of illicit pleasure and pain. He also demonstrated a weakness for alcohol, with a preference for the deadly green absinthe. After an extended period of debauchery, he met and in 1870 married a young girl, Mathilde Mauté, who seemed the epitome of unsullied virginity.

Verlaine settled down briefly to a civil service job, but the Franco-Prussian War soon broke out, and the arrival in Paris of Arthur Rimbaud in 1871

ended forever any semblance of bourgeois respectability in Verlaine’s life. His affair with Rimbaud lasted two years, followed by 18 months in prison for having assaulted the younger poet. While in jail, Verlaine consoled himself with religion.

From then on Verlaine lived as a sexual vagabond, wandering from one disastrously messy relationship to another, alternating between violence and penitence, sobriety and debauchery, quarrels and reconciliation—all the while

distilling the essence of his experience into verse. Even during affairs he lived with his mother in a tempestuous love-hate relationship which frequently erupted into open battles.

After his mother’s death in 1886, Verlaine returned to heterosexuality for the first time since his marriage. His health was declining (his many complaints included cirrhosis of the liver, a heart condition, and a “bad leg,” possibly caused by tertiary syphilis), and he spent nearly half of his last years happily ensconced in public hospitals, where he was cared for like a baby and regaled as a celebrity. Two years before his death from pneumonia, he was elected “prince of poets,” by the young poets of Paris.

MATHILDE:

For Verlaine, it was love at first sight when he met the proper 16-year-old girl who admired his poetry. Having already seen the poet in literary circles, Mathilde was not put off by his appearance. Indeed, the infatuated Verlaine was so happy, Mathilde later wrote, that “he ceased to be ugly, and I thought of that pretty fairy tale, ‘Beauty and the Beast,’ where love transforms the Beast into Prince Charming.”

During their 10-month engagement Verlaine remained adoringly devoted and chaste, writing trite poetry which idealized love. Marriage, however, revealed “Beauty” to be a vain and snobbish bourgeoise, while “Prince Charming” reverted to the “Beast.” He began to drink again, acting out his ambivalence, alternating between gentleness and brutality. He once tried to set his wife’s hair on fire, and in a burst of rage hurled his infant son against a wall.