The Illusion of Conscious Will (43 page)

Read The Illusion of Conscious Will Online

Authors: Daniel M. Wegner

Tags: #General, #Psychology, #Cognitive Psychology, #Philosophy, #Will, #Free Will & Determinism, #Free Will and Determinism

Identity and the Subjective Self

One way of appreciating identity is to note the continuity of subjective experience over time, the sense we have that we are agents who do things and experience things, and who in some regard are the same from one time to another. This sense of identity is inherent in the aspect of self that William James (1890) called the “knower,” the self that is the seat of experience, the self that is doing all our thinking and living. Another way of conceptualizing identity is to speak of the self as an object one can think about, the aspect of the self that James called “known.” People who speak of “self-concept” often are referring to this latter definition of identity, and in fact there are many theories of how people think about themselves (Baumeister 1998; Swann 1999; Wegner and Vallacher 1980). These theories examine the properties people attribute to themselves, how they evaluate themselves, and how these judgments of self influence behavior. There are very few accounts, however, of how the subjective self—the knower—is constituted. The notion of virtual agency is all about this and so opens up a new way of theorizing about an aspect of self that has previously been something of a mystery.

If it weren’t for strange things like spirit possession and channeling, we might never have noticed that the subjective self can fluctuate and change over time. It is only by virtue of the ways in which people step outside themselves—to see the world from new perspectives, as different agents, with radically different points of view—that it becomes possible to recognize what an exciting and odd thing it is to have a subjective self at all. The subjective self each of us inhabits, in this light, is just one virtual agent of many possible virtual agents. Admittedly, the normal person’s point of view is pretty stable; it takes a lot of drumming and believing and channeling lessons and who knows what else to get people to switch identities through the methods we’ve investigated so far. Yet such switching makes it possible to imagine that the self is not too different from a spirit—an imagined agent that is treated as real and that has real consequences for the person’s behavior and experience.

12

We now look into the very center of this fabrication of the subjective self—first by examining the topic of dissociative identity disorder, in which transformations of self and identity are endemic, and then by focusing on how the sense of virtual agency is constructed so as to give rise to the experience of being an agent.

Multiple Personalities

People who seem to have more than one personality have been noted from time to time in history. Perhaps the best-known instance is fictional,

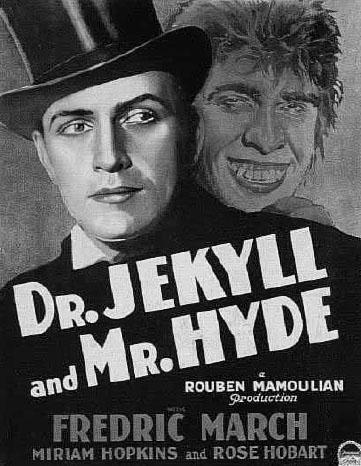

The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde

by Robert Louis Stevenson (1886;

fig. 7.6

). The earliest nonfictional accounts of multiple personalities involved people who split into two, like Jekyll and Hyde, but later cases came to light in which people adopted many different identities, including, for example, the widely read case of “Miss Christine Beauchamp,” described by Morton Prince (1906). Reports of cases continued through the 1920s until a period in which almost no cases were reported for forty years.

12.

Dennett (1992) proposes a similar concept of the agent “self as the center of narrative gravity.”

Figure 7.6

One of the movie versions of Robert Louis Stevenson’s

The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde.

Perhaps because of confusion between multiple personality disorder and the far more prevalent diagnosis of schizophrenia, few cases were observed, and there were several pronouncements that multiple personality disorder might not exist (Taylor and Martin 1944; Sutcliffe and Jones 1962).

13

Then, however, a best-selling book,

The Three Faces of Eve

(Thigpen and Cleckley 1957), and a movie of the same name starring Joanne Woodward, drew popular attention and scientific interest to the disorder. The book

Sybil

(Schreiber 1974), and its TV movie (with Sally Field as the victim and Joanne Woodward as the therapist) had further impact. The incidence of a syndrome once so rare that its existence was in doubt has since grown to thousands of documented cases, and the disorder has been accorded formal diagnostic status as dissociative identity disorder (DID) in the

DSM-IV

(1994).

13.

Putnam (1989) provides a balanced and thorough account of this history. Still, it is interesting to note that the question of whether dissociative identity disorder exists remains a matter of some debate (Acocella 1999). Humphreys and Dennett (1989) offer an illuminating outsiders’ view of the continued scrapping among the insiders.

In this disorder, an individual experiences two or more distinct personalities or personality states, each of which recurs and takes control of the person’s behavior. There is usually a main personality, which is often dull, depressive, and quiet. As a rule, the other personalities seem to develop to express particular emotions or to fit certain situations that the central personality does not handle well. So there may be a lively, extroverted personality, a childlike personality, personalities of the opposite sex, personalities that express extreme anger or fear, or personalities that have witnessed traumatic events the main personality knows nothing about. There may be an “internal self-helper” personality that tries to make peace among the others, or an “internal persecutor” personality that badgers the main personality (Putnam 1989). The number of personalities emerging from one individual may number from a few to hundreds, and the trend in recent cases has been for more personalities to be observed. Far more women than men suffer from the disorder.

Some of the central features of the disorder can be seen in Morton Prince’s (1906) analysis of Miss Beauchamp. In this case, the main personality was one that Prince came to call “the saint.” She was morbidly conscientious, prudish, patient, and deeply religious, and consulted Prince because of her headaches, insomnia, nervousness, fatigue, and depression. He undertook a program of therapy and hypnosis with her, and one day under hypnosis she referred to herself not as “I” but as “she.” Asked why, she explained “because she is stupid; she goes around mooning, half asleep, with her head buried in a book” (Prince 1906, 28). This new personality called herself Sally. The original personality (which Prince later labeled B1) knew nothing of Sally, but Sally was co-conscious with B1—knowing B1’s thoughts and being able to influence her behaviors even without B1’s knowledge. Sally deeply disliked B1 and would play tricks—she would tear up her letters, conceal money and stamps, and even sew up the sleeves of B1’s clothes. She sent through the mail to B1 packages containing spiders, spent money lavishly on unsuitable clothes, broke B1’s appointments, and walked out on jobs B1 had worked to keep (Wilkes 1988).

Later on, other personalities came forward, and Prince noted and labeled them although not all named themselves. He identified each personality’s hypnotized state as another personality (for example, B1a was the hypnotized B1), and he noted differences in style and memory access between them. These personalities were generally unknown to B1, and some were also unknown to each other. A personality Prince called B4 emerged during their conversations (not during hypnosis), of which B1 knew nothing. Sally was conscious of B4’s actions but not of her thoughts, and B4 knew nothing directly of either B1 or Sally. Sally continued to play the persecutor and was able “by a technique she described as ‘willing,’ to induce positive and negative hallucinations in both B1 and B4; she could induce aboulia (failure of will) or apraxia (inability to act), especially if the primary personality was, as she put it, ‘rattled’; she could tease B1 by making her transpose letters of words she was writing . . .” (Wilkes 1988, 126). In this case and others, the personalities have differing levels of awareness of each other and control of the body.

The process of changing from one personality to another doesn’t take very long. Putnam (1994) made observations of the switching process in DID patients and concluded that it takes about one to five minutes for a switch. He observed that “most, but not all, patients exhibit either a burst of rapid blinking or one or more upward eye rolls at the beginning of the switch . . . [which] may be followed by a transient ‘blank’ or vacant gaze. . . . [There] is a disturbance of ongoing autonomic regulatory rhythms, particularly heart rate and respiration, together with a burst of diffuse motor discharge” (295). When the switch occurs, there is often a shift in expressed emotion (e.g., from depressed to euphoric or angry) sometimes a change in voice or speech frequency, rate, or volume, and occasionally a rearrangement of facial muscles in a stepwise fashion through a series of grimaces. There may be postural shifts after the initial switch as the new personality seems to get comfortable and exercise the body (Putnam 1994, 295).

The switch process is reminiscent of the shtick that impressionist comedians do when they change into a character they are impersonating— looking away, shrugging their shoulders, and then turning around with a new expression. And, indeed, some commentators have understandably wondered whether patients are voluntarily pretending. Joanne Wood-ward looked very convincingly different as the characters Eve White and Eve Black in

The Three Faces of Eve,

yet she was an actress, not a multiple. It makes sense that people might be acting their multiple personalities. Perhaps, like those who develop spirit possession in order to express forbidden impulses, people become susceptible to multiple personality for instrumental reasons. Perhaps, also as in possession, people develop multiple personality through a self-induction process that begins with pretending and proceeds into uncontrollable changes.

The strange transition of DID from a once rare disorder to the “flavor of the month” of psychological problems has raised concerns that the disorder is indeed a matter of faking or fashion (Spanos 1994). The most common suggestion is that DID is caused by psychotherapists who, though often well-meaning, have searched so hard for evidence in patients who are vulnerable to their suggestive procedures that they have ended up creating the disease. Accounts of how therapists treat DID show indications of cajoling, suggesting, coaxing, and even bullying clients into reporting evidence of alter personalities, and many of the names for alters indeed are created by therapists (Acocella 1999). Dissociative disorders may have been created, rather than treated, through seriously flawed therapeutic and self-help procedures like those that try to recover “repressed memories” (e.g., Bass and Davis 1988) and instead insert false memories into the minds of clients (Ofshe and Waters 1994). There is evidence that new multiple personality cases tend to arise in communities primarily when therapists who believe in this disorder come to town. Acocella (1999) recounts a number of such instances and also points out numerous cases in which people once diagnosed with DID have become “retractors” and have successfully sued their therapists for causing their disorder. She concludes that the study of multiple personality disorder is “not a science but a belief system” (Acocella 1999, 81).

In this sense, the current wave of DID diagnoses may be understood as arising from belief processes much like those that underlie the creation of possession in religious groups or of spirit channeling in new-age believers. Multiple personality may be less a fundamental psychological disorder than a manifestation of the human ability to assume multiple virtual agents in response to strong social pressures and deeply held beliefs. The stories of Eve and Sybil may have given many people cultural recipes for the self-induction of new virtual agents and simultaneously instructed unwitting therapists in how to help them along.

14

What evidence is there for the reality of multiple personalities? Perhaps the most basic fact is the sense of involuntariness that patients feel for the behavior they perform while in other personalities. The change process, too, is not usually reported to feel voluntary. Although switches can often be made on demand, when the therapist asks a patient to change, the changes may occur without the patient’s knowledge or feeling of will (Spiegel and Cardeña 1991). This means that patients can have difficulties maintaining effectiveness in work, relationships, and life in general. One personality may take a prescription medicine in the morning, for instance, and others may take their own doses as they emerge during the day, leading to an overdose by evening. Or one personality may make an appointment, but the personality in control at the time of the appointment is amnesic for the information and misses it. Given that the personalities can be at odds with each other, these inconveniences may be complicated further by serious internal struggles, in some cases culminating in extreme self-injurious behavior. Although DID may evolve from self-induction processes, it develops into a problem that is not then susceptible to immediate conscious control (Gleaves 1996).