The Illusion of Conscious Will (38 page)

Read The Illusion of Conscious Will Online

Authors: Daniel M. Wegner

Tags: #General, #Psychology, #Cognitive Psychology, #Philosophy, #Will, #Free Will & Determinism, #Free Will and Determinism

The prospect of this radical transformation is what makes the study of action projection to imaginary agents particularly exciting and at the same time strange, verging on the surreal. Although some kinds of action projection to imaginary agents seem entirely commonplace, others take off directly to Mars. Unlike projection to real agents, which involves the misperception of a real situation, action projection to imaginary agents can be understood as a glitch of an action accounting scheme inside the actor’s own head. There is no one else really there to have done the action except for some imaginary agent. This glitch, however, has profound effects on the person’s consciousness. At the extreme, the attribution of agency to imaginary minds other than the self seems to annihilate the self and thus wreaks havoc on our intuitions about personal identity and the continuity of conscious life.

In this chapter, then, we walk on the wild side. We examine action projection to imaginary agents of all kinds, beginning with ordinary forms of pretend play and role enactment, and proceeding to cases of channeling and mediumship, spirit possession, and dissociative identity disorder. With luck, we will emerge knowing more about how our own agent selves are constituted.

Imaginary Agents

There are two essential steps in the process of creating a new agent inside one’s head. First, the agent must be imagined. Second, the imagination must be mistaken for real. Once this has happened, the processes that create action projection can start churning to produce all kinds of new actions attributable to the imaginary agent. Several key circumstances can promote the occurrence of these steps and thus yield active agents in the person.

Imagining an Agent

It is easy enough to imagine a conscious agent. Children do it all the time. Marjorie Taylor (1999) has made a detailed study of one such phenomenon in her book on imaginary companions. She reports that a substantial proportion of children in her samples of preschoolers report having imaginary companions, who may be other children, adults, puppies, aliens, clowns, robots, fairies, or oddities such as talking cotton balls, and who may appear singly or in groups. Children interviewed about their imaginary companions had stable descriptions of them over the course of seven months, although some were forgotten even in this short time. The children usually express attachment to and fondness for these companions, and also report playing with them frequently. They freely call them imaginary, however, and in most cases are quite happy to relegate the companions to a status distinct from that of real agents. Children with and without such companions do not differ in their ability to distinguish fantasy and reality, and Taylor reports that having such companions is not at all an unhealthy sign. Instead, it seems to be associated with a facility for creativity and an ability to pretend. Children with imaginary companions were more likely, for example, to hold an imaginary object instead of substituting a body part when performing a pretend action, as when they pretended to use a toothbrush rather than extending a finger to indicate the brush (Taylor, Cartwright, and Carlson 1993).

Eventually, of course, children with imaginary playmates abandon them and join other children, and they all then graduate to become adults with seemingly less active imaginations. Children sort out many of the magical and wishful entities from real ones, and learn, too, which entities— such as the Tooth Fairy, angels, or the devil—might still be okay to talk about even though they can’t be authenticated by the usual means (Woolley 2000). Adults and children alike continue to perceive an amazing array of people, animals, or spirits in their everyday worlds. In

Faces in the Clouds,

Guthrie (1993) displays a wealth of examples of such anthropomorphism (

fig. 7.2

) in art, humor, philosophy, advertising, literature, engineering, science, and religion. The theme of his book is that the thoroughgoing human tendency to see agents all around us in the form of ourselves culminates naturally in the perception of a God who is also quite human in temperament and psychology.

2

The proclivity to believe that there is a God, or more than one god, is consistent with our willy-nilly perception of agents everywhere, although in this case the agent is writ large as an ideal agent, a best possible mind. God may be the ultimate imaginary friend.

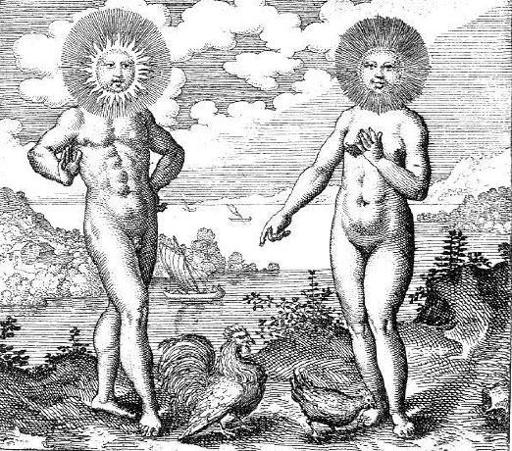

Figure 7.2

Anthropomorphism takes many forms. In this seventeenth-century etching by Michel Maier, the sun is a man and the moon is a woman. The parts of the chickens are played by themselves. From Roob (1997).

2.

It is interesting that the conception of God held by North Americans, at any rate, is highly anthropomorphic in that people can’t seem to conceive of a Deity that is unlike a person. In a clever study, Barrett and Keil (1996) presented people with stories of various agents who were called on to help one person while they were already helping another. The researchers found that when the agent was described as a person, participants recalled that the agent had to stop attending to the first person in order to help the other; when the agent was described as a supercomputer, however, participants recalled the computer’s helping both people simultaneously. However, when the agent was described as God, the participants remembered the Deity in a very human way, as having to stop attending to one person in order to help the other. Like the absurdity of a Santa Claus who must sequentially climb down billions of chimneys in one night, anthropomorphism leads people to intuit a difficult theology in which God cannot multitask.

Social psychologists have long appreciated the person’s ability to understand and create roles and dramas, playing one position against the other—all inside the head (Goffman 1959; Sarbin and Allen 1968). The fact is, we have a well-developed sense of the other person in our own minds. In routine situations such as at a restaurant, for example, we have self and other so well rehearsed that we know when anyone has fouled up in even the most minor way (Schank and Abelson 1977). Patrons know almost instantly if the waitperson doesn’t follow the script (“Why did he not ask to take my order?”). Waitpersons are similarly alert to unscripted patron behaviors (“When I asked if she wanted fries with that, she just said ‘perhaps’”). In nonroutine situations the interplay of self and other that can happen in our own heads is often so innovative that it can be informative and downright entertaining. Witness the times you’ve thought through the various ways that some tricky interaction might unfold and have worked out in your mind how it might go if you asked the boss for a favor or tried to make friends with that interesting stranger.

The mental invention of other people is paralleled by a similar kind of imagining about ourselves. We can invent people or agents whom we

imagine ourselves being

and so create selves that may be quite different from the ones we usually inhabit. We can imagine not only how we might react to the waitperson in that restaurant, for example, we can also imagine how we might react

as

the waitperson. The ability to imagine people’s visual perspectives, goals, and likely behaviors and perceptions in a situation gives us the ammunition to pretend to be those people. People seem to have the ability to take roles—to assume certain physical or social perspectives—that consist of general mental transformations of world knowledge. We can switch mentally between the viewpoint of a person standing outside a car facing it and a person sitting inside a car facing out, for example, and then make rapid judgments of specific changes (e.g., the steering wheel will now be on the left) based on this global change. We can similarly switch perspectives from waitperson to diner, from patient to doctor, or from parent to child, at least to a degree. This ability develops as children interact with the world and each other (Flavell et al. 1968; Piaget and Inhelder 1948) and is only available in a most rudimentary form among even our most accomplished chimpanzee and monkey friends (Povinelli 1994; 1999).

Taking on the perspectives or roles of others is not merely play; it can become deeply involving and may manifest many of the properties of real interaction. Consider the invention of own and other identities that occurs in theater. The first role you take in a high school play, for example, involves not just learning lines and figuring out where to stand. You may suspect that this is the whole project when you first volunteer, but you soon realize there is much more to it. There is a sense in which you must imagine a whole person and put that person on like a glove or a suit of clothes. In the desire to act more authentically, some students of acting adopt the “method” approach (Stanislavski 1936). This involves attempting to experience the emotions of the character one is playing. Although we don’t know whether this enhances the actor’s experience or imagining of the character, there is some evidence that it does improve the quality of the role enactment (Bloch, Orthous, and Santibañez-H. 1995).

Treating imaginary agents as though they are real can eventually lead to a strong sense of involvement with the agents and concern about their pursuits. The world of interactive role-play gaming depends on this kind of appeal. Games such as

Dungeons and Dragons

have entranced enough people in the last generation to create an entire subculture (Fine 1983). And interactive fantasy has jumped to whole new levels in computer-based environments such as chat rooms and other MUDs (multiuser domains). Sherry Turkle (1995) recounts the rich and detailed stories and identities that people have created in the process of playing roles and forming interactive fantasies. When the individual adopts an avatar or virtual identity and begins to interact in such a community, he or she can invent whole people—not just as imaginary others but instead as imaginary selves. The process of imagining people can grow through role-playing to become a process of creating a new identity, complete with wings, a floppy hat, red shoes, and a big purple nose.

3

In most of these cases of imaginary agents—be they childhood companions or characters in plays or games—we are quite conscious that they are imaginary. We know, at least at the outset, that we are embarking on an imaginary exercise, and though the world we’ve created may seem quite real in the heat of the action, we still have that sense that it was all imagined when it is over. These various forms of imagining have in common a kind of “as if” quality, a background recognition that they are not real, that demarcates them sharply from the kind of experience reported by people who have dissociative identity events. In normal garden-variety imagining, we

know that the imagined persons are imaginary

. As long as this knowledge is retained, we do not actually become the persons we imagine being, nor do we presume actually to interact with the persons we imagine meeting. What, then, pushes people over the edge? When does the imagining turn real?

Cues to Reality

People decide that imaginary persons are real in the same way they decide that anything is real. There are reality cues, various hints that can be used to distinguish the real from the unreal (Brickman 1978; Gorassini 1999; Johnson and Raye 1981; Johnson, Hashtroudi, and Lindsay 1993; Schooler, Gerhard, and Loftus 1986). It is just that in the case of imaginary agents we mistake for real, the cues

falsely

point to reality. Consider the case of a completely unreal experience that often seems resoundingly real—a dream. When we’re in the middle of a dream, it may be difficult to distinguish the dream world from the real world.

4

No matter how fantastic or strange, the dream world is real at the time we are in it. All the cues are there: Everything

seems

real in that we have rich and detailed input to the mind’s eye, the mind’s ears, and the mind’s other senses (although curiously, we don’t get smell in dreams; Hobson 1988). Everything also

feels

real; we can get tremendously worked up about what is happening. We react with emotion—becoming afraid, angry, embarrassed, tickled, or overjoyed, and sometimes having orgasms or heart attacks as well. And everything

acts

real; things behave in ways we cannot anticipate or control. In short, things seem real when they have

perceptual detail,

feel real when they have

emotional impact,

and act real when they are

uncontrollable

. Just as in a dream, when we imagine agents in waking life in ways that create these same three cues, we are more likely to judge the agents as real.

3.

Hans Suler (1999) has created an interesting and detailed Web page on this.

4.

Some people insist that they have dreams in which they know that they are dreaming. This has been called lucid dreaming, and there is a fair amount of descriptive material suggesting that many people share this sense at times (e.g., Kahan and LaBerge 1994). However, it is also possible that such dreams occur primarily when people are just waking up or falling asleep and become aware of the fact that they are dreaming through the juxtaposition of the dream with the waking state.