The History of the Medieval World: From the Conversion of Constantine to the First Crusade (6 page)

Authors: Susan Wise Bauer

Travelling to Pataliputra, the Gupta capital, he was even more impressed with both the wealth and the spirituality of its inhabitants: “The inhabitants are rich and prosperous,” he wrote, “and vie with one another in the practice of benevolence and righteousness.” As for the city itself, where Chandragupta II’s palace stood, he calls it “[t]he city where King Asoka ruled,” and praises Chandragupta II for taking the same position as the earlier king towards Buddhism: “The Law of Buddha was widely made known, and the followers of other doctrines did not find it in their power to persecute the body of monks in any way.”

13

Like his father, Chandragupta II had managed to associate himself with the glorious and partly mythical past.

Chandragupta II ruled for nearly four decades. After his death in 415, he became a legend: the wise king Vikramaditya, subject of heroic tales and mythical songs. He left behind him an empire that, though at its core not much larger than in the days of Samudragupta, claimed nominal control over the southeast, west, and north, covering all but the southwest quarter of the subcontinent. It was an empire where control was untested, where orthodoxy was untried, and where loyalty was not needed: an empire of the mind.

TIMELINE

3

CHINA | INDIA |

Fall of Han (220)/Rise of Three Kingdoms: Shu Han, Cao Wei, Dong Wu | |

Wei Yuandi | |

Destruction of Shu Han (263) | |

Fall of Cao Wei/Rise of Jin (265) | |

Jin Wudi | |

Destruction of Dong Wu (280) | |

Unification under the Jin (280–316) | |

Rebellion of the Eight Princes (291–306) | |

Jin Huaidi | |

Liu Cong | |

Fall of unified Jin (316) | |

Jin Yuandi | Chandragupta |

| Samudragupta |

Fu Jian of the Qianqin (357–385) | |

Battle of the Fei River (383) | Chandragupta II |

Rise of Bei Wei (386) | |

Tuoba Gui of the Bei Wei (386–409) | |

| Faxian journeys to India |

Between 325 and 361, Shapur II of Persia challenges the Roman empire, Constantine plans the first crusade, and his heirs fight each other for power

N

OW THAT HE HAD MOVED

his capital city eastward, Constantine was face to face with his most dangerous enemy: the king of Persia.

Shapur II had been king since he was in the womb. His father, Hurmuz, had died a month before Shapur’s birth, and the Persian noblemen and the priests of the state religion, Zoroastrianism, had crowned the queen’s pregnant belly. Until he turned sixteen, Shapur and his empire were controlled by regents who were more concerned for their own power than for the greater good of Persia. So Persia had been unable, during Constantine’s rise to power, to do much in the way of seizing land for itself.

In fact, it had been forced into defending itself from southern invasion: tribes of kingless and nomadic Arabs who had lived in the Arabian peninsula for centuries were now driven northward by a sinking water table. Because of the harshness of their own native land, says the Arab historian al-Tabari, they were the “most needy of all the nations,” and their raids were growing more troublesome: “They seized the local people’s herds of cattle,” al-Tabari laments, “their cultivated land, and their means of subsistence, and did a great deal of damage…with none of the Persians able to launch a counterattack because they had set the royal crown on the head of a mere child.”

1

This lasted only until Shapur attained his majority, which he did early. In 325, he told his army commanders that he would now take over the defense of the empire. He selected a thousand horsemen to act as a strike force against the Arab invaders, under his personal command. “Then he led them forth,” al-Tabari writes, “and fell upon those Arabs who had treated Fars as their pasture ground…wrought great slaughter among them, reduced [others of] them to the harshest form of captivity, and put the remainder to flight.” He then pursued them, sending a fleet of ships across the Persian Gulf to Bahrain, landing in eastern Arabia, and shedding “so much of their blood that it flowed like a torrent swollen by a rainstorm.”

2

His forces reached as far as the small oasis city of Medina, where he took captives.

Nevertheless, it was not this force at arms that impressed al-Tabari the most. Shapur’s wisdom, al-Tabari tells us, was first seen when, as a young man, he watched his people crossing a bridge over the Tigris, pushing against each other on the crowded span. This struck him as inefficient.

So he gave orders for another bridge to be built, so that one of the bridges could be used for people crossing in one direction and the other bridge for people crossing from the opposite direction…. In this way, the people were relieved of the necessity of endangering their lives when crossing the bridge. The child grew in stature and prestige in that single day, what for others would have taken a long period.

3

Running an empire the size of Persia required more than skill with a sword; it took administrative ability. Inventing a new traffic pattern was an innovation. Shapur II was intelligent and shrewd, and fully able to withstand Constantine’s plans to dominate the known world.

Constantine’s move to Byzantium was silent testimony that he intended to challenge Persia’s hold on the east. But his first approach to Shapur II was relatively polite. As soon as Shapur II shook off his regents, Constantine sent him a letter suggesting in respectful but unambiguous terms that Shapur refrain from persecuting the Christians in Persia. “I commend [them] to you because you are so great,” Constantine wrote, tactfully. “Cherish them in accordance with your usual humanity: for by this gesture of faith you will confer an immeasurable benefit on both yourself and us.”

4

Shapur II agreed to show mercy to the Christians within his border, but this tolerance became increasingly difficult as time went on. Not long after Constantine’s missive, the African king of Axum became a Christian—an act that proclaimed his friendship with the Roman empire as loudly as it proclaimed his hope of heaven.

T

HIS KING

was named Ezana, and the kingdom he ruled lay just west of the Red Sea.

*

On the other side of the narrow strait at the sea’s southern end was Arabia, and in the 330s Arabia was filled with Persian soldiers. Shapur the Great, who had driven the invading Arabs out of his southern realm at the beginning of his reign, had continued an enthusiastic campaign into the Arabian interior. For his entire reign, al-Tabari tells us, Shapur was “occupied with great eagerness in killing the Arabs and tearing out the shoulder-blades of their leaders; this was why they called him Dhu al-Aktaf, ‘The Man of the Shoulders.’”

*

Ezana’s conversion assured him of Constantine’s support, should Persian aggression move across the water.

5

For the moment, Shapur left the African kingdom alone. Instead, his soldiers invaded Armenia.

Armenia, which had been a kingdom for nearly a millennium, had long suffered from its position on the eastern frontier of Rome. For centuries, Roman emperors had either allied themselves with the Armenian kings or invaded the kingdom in an effort to make it part of the empire; the eastern kingdoms of the ancient Persians and Parthians had done the same, hoping to make Armenia a buffer against Roman expansion.

At the moment, Armenia was independent, but once again squeezed between two large and expanding empires. It was not at war with either Rome or Persia, but it tended towards friendship with the Roman empire. The king of Armenia, Tiridates, had been baptized by a monk named Gregory back in 303, before Christianity was politically useful.

6

When Constantine made Christianity the religion of the empire, Armenia’s ties with its western neighbor grew even stronger.

Agents of Shapur the Great—who was increasingly worried that a Christian Armenia would never again serve as an ally of the Persian empire—managed to convince Tiridates’s chamberlain to turn traitor. In 330, the chamberlain poisoned his king. Unfortunately for the Persians, this did not turn Armenia away from Christianity; instead, Tiridates became a martyr (and eventually a saint), and his son Khosrov the Short became king.

Since the indirect approach had failed, Shapur sent soldiers. The 336 invasion of Armenia failed—the soldiers withdrew—but Shapur had conveyed a clear message to Constantine: he didn’t intend to relinquish the border areas to Rome, even if those border areas were Christian.

Converting to Christianity had now gained all sorts of fraught political implications, and Shapur decided to crack down on Christianity in his own empire. In Persian eyes, Christians were increasingly likely to be double agents working for Rome. The systematic persecution of Persian Christians, mostly on the western frontier, began early in 337.

The attacks were recorded by the Persian Christian Aphrahat, who lived at the monastery Mar Mathai, on the eastern bank of the Tigris river. Shapur, he wrote to a fellow monk who lived outside Persia, caused “a great massacre of martyrs,” but the Persian Christians were holding strong; they believed that they would be blessed with a “great reward,” while the Persian persecutors would “come to scorn and contempt.”

7

To the west, Constantine was plotting to make those words come true. He was preparing an invasion, but this invasion would be a crusade; his justification was that the Christians of Persia needed his help. He planned to take with him a portable tabernacle, a tent in which bishops (who would accompany the army) would lead regular worship, and he announced that he would be baptized (something he hadn’t yet gotten around to) in the river Jordan as soon as he reached it. It was the first time that a ruler had planned to wield the cross against an outside enemy.

8

But before he could depart on his crusade, he grew sick; and on May 22, 337, Constantine the Great died.

The name of his city was changed from Byzantium to Constantinople, in his honor, and he was buried there in a mausoleum he had prepared at the Church of the Holy Apostles. The mausoleum had twelve symbolic coffins for the twelve apostles in it, with Constantine’s as the thirteenth. Later historians called this an act of massive hubris, but the burial had its own logic: Constantine, like the apostles, was a founder of the faith. “He alone of all the Roman emperors has honoured God the All-sovereign,” Eusebius concludes, “…[H]e alone has honoured his Church as no other since time began…. [H]is like has never been recorded from the beginning of time until our day.” He had married Christianity and state politics, and in doing so had changed both forever.

9

A

S SOON AS NEWS

of Constantine’s death spread eastward, Shapur invaded Armenia again. This time he succeeded; Armenia’s Christian king, Khosrov the Short, was forced to run for his life towards the Roman border. Shapur installed a Persian puppet in his place. The buffer kingdom was, at least temporarily, his.

10

The Roman response was not immediate because Constantine’s heirs were busy trying to kill each other in Constantinople. Constantine, canny politician in life, had made no definite arrangements for the succession; it was almost as though he expected to live forever. Instead, he left behind three sons and a nephew who had all been given the title of Caesar, who had all ruled for him in various parts of the empire, and who could all claim the right to the throne.

No impartial historian records exactly what happened in the weeks after Constantine’s death, but by the time the bloodshed ceased, Constantine’s nephew, both of his brothers-in-law, and a handful of high court officials had been murdered. Constantine’s three sons—Constantine II (twenty-one), Constantius (seventeen), and Constans (fourteen)—had come to some sort of family agreement that left the three of them alive and all possible competitors or naysayers dead.

11

The only exception was their five-year-old cousin Julian, who was being raised in a castle in Asia Minor, well away from the purge.

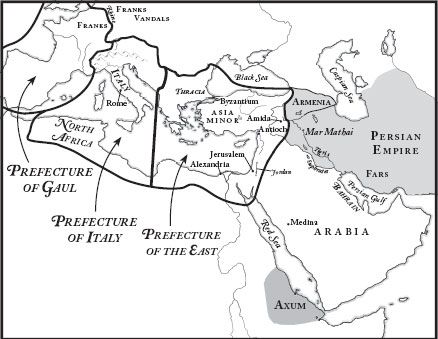

4.1: The Romans and Persians

In September, the three sons had themselves acclaimed as co-emperors in Constantinople. The empire was again divided, this time into three parts (or prefectures). Constantine II took the Prefecture of Gaul; Constans took the Prefecture of Italy, which included not only Rome but also North Africa; and Constantius took the entire Prefecture of the East along with the region of Thracia, which meant that he got Constantinople. Almost at once, Constantius reinvaded Armenia and put Khosrov the Short back on his throne.

Fourteen-year-old Constans, despite his age, soon showed that he was not to be trifled with. In 340, his brother Constantine II tried to take Italy from him; Constans went to war against his older brother, ambushed him in the north of Italy, and killed him. Now the empire was again divided into two, between Constans in the west and Constantius in the east.

Constans was a staunch supporter of the Christian church; nevertheless, he was unpopular with everyone. His personality was so foul that even the church historians, normally fulsome about any Christian emperor, disliked him. He managed to survive for another ten years, but in 350, at age twenty-seven, he was murdered by his own generals.

12

Rather than throwing their support behind the remaining brother, Constantius, the generals then acclaimed a new co-emperor: an officer named Magnentius. Constantius marched west to get rid of the usurper, but it took two years of fighting before Magnentius was defeated. He killed himself rather than fall into Constantius’s hands. By 352, Constantius (like his father) was ruler of the entire empire.

Meanwhile, of course, Constantius had been away from his eastern border; and Shapur had taken advantage of his absence to reclaim Armenia yet again. The son of Khosrov the Short had been ruling as a Roman ally; Shapur invaded, captured the king, put out his eyes, and allowed his son to ascend the throne only on the condition that he remain subject to Persian wishes.

13

Constantius did not immediately answer this challenge. He had problems to solve, the most pressing of which was finding an heir. He had no son, so in 355 he appointed his surviving cousin Julian to be Caesar and heir. Julian, now twenty-three, had been squirreled away in Asia Minor, being carefully trained in Christianity by the tutor Mardonius.

Constantius preferred to reside in Constantinople, so he put Julian in charge of affairs on the western side of the empire. Here, the young man campaigned so successfully on the Rhine front that the army became his enthusiastic supporter; when he reduced taxation in the west, the people loved him too.

While Julian’s popularity grew, Constantius’s waned. Like his father, Constantius was a Christian; unlike his father, he was supportive of Arianism, now officially a heresy. In the same year that he appointed Julian as his Caesar, Constantius wielded his imperial authority to get rid of the bishop of Rome, an anti-Arian churchman named Liberius who disapproved of Constantius’s beliefs. In Liberius’s place, he appointed a bishop of his own choosing.