The History of Florida (60 page)

Read The History of Florida Online

Authors: Michael Gannon

Tags: #History, #United States, #State & Local, #Americas

their workshops to nearby Key West. In 1885, the City of Tampa offered to

give one of Key West’s cigar makers, Vicente Ybor, a tract of land east of

town if he would build a factory there. Ybor took up the offer, and soon

Ybor City grew into a cosmopolitan community of Cubans, Italians, and

Spaniards with a vibrant culture all its own. Other Florida towns also had

cigar factories operated by immigrants from Cuba.

Commercial fishing off both the Atlantic and Gulf coasts grew in im-

portance as railroads and refrigerator cars made it possible to market catch

in the North. Before the Civil War, beds of sponges had been discovered

growing off Key West, but it would not be until the 1880s that demand for

sponges soared. New sponge grounds were found off Florida’s west coast,

and Tarpon Springs became home port for a fleet of boats that sent out

Greek divers in metal helmets attached to air hoses to go down and bring

up the sponges.

286 · Thomas Graham

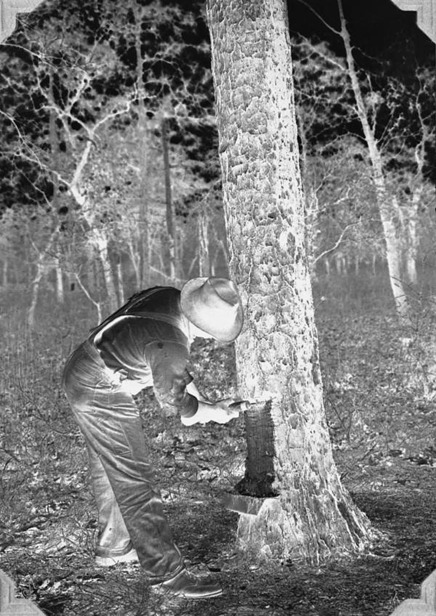

Workers hacked “faces”

into the bark of pine trees

to create a flow of sap into

cups. Since the work had

to be done in remote for-

ested areas, leased convict

labor was often employed

since free men would not

have tolerated the harsh

living conditions. Courtesy

of the State Archives of

Florida,

Florida Memory

,

http://floridamemory.

proofcom/items/show/11021.

Oranges had long been an iconic symbol of Florida, but the industry suf-

fered periodic setbacks. Freezing-cold snaps in 1886, 1894, and 1895 wiped

out many of the groves and forced replanting to take place farther down

the peninsula. Along the southeast coast, pineapple cultivation enjoyed a

short-lived bonanza in the 1890s. Winter vegetables actual y produced more

income for Florida farmers than oranges, partly because it took seven years

for an orange grove to mature while vegetables could yield profits within a

few weeks. Cold Yankees in wintertime had an insatiable appetite for Flor-

ida carrots, cabbages, tomatoes, and beans. St. Johns County discovered

that Irish potatoes grew very well in Florida soil. The profitability of these

perishable crops depended upon rapid railroad transportation to northern

markets.

At this time fashionable women wore large, elaborate hats often deco-

rated with the delicate snow-white feathers of “plume birds.” The highest-

quality feathers came from birds shot at nesting season. Florida was home

to millions of plume birds, and frontier hunters would make difficult treks

into wetlands seeking out the rookeries where great flocks of birds nested

The First Developers · 287

in colonies. Killing the birds was comparatively easy since the parent birds

would hover over their nests trying to protect their chicks.

This wanton slaughter of birds aroused the indignation of early conser-

vationists, many of them women. Florida passed a law in 1879 that forbade

noncitizens from killing plume birds and in 1891 outlawed their commercial

hunting. In 1900, the Florida Audubon Society was organized to dissemi-

nate information about the destruction of the state’s bird life and to encour-

age women to boycott feathers used as decorations. In 1901, the Florida leg-

islature passed another law to prohibit hunting of plume birds, but made the

penalty for violation a small fine, with no provision to hire game wardens to

enforce the law. The Audubon Society employed and paid its own wardens,

but when two of them were murdered, the society gave up the battle. At least

some parks were created as sanctuaries. President Roosevelt established Pel-

ican Island Wildlife Refuge on Indian River in 1903, and the state set aside

Royal Palm Park in the Everglades in 1916 as Florida’s first state park.6

The presence of tropical fevers had long been a deterrent to the settle-

ment of Florida. In June 1887, people in Key West began dying of yel ow

fever. Outbreaks fol owed in Tampa and along the rail lines leading away

from Tampa. Towns in Florida not touched by the epidemic imposed quar-

antines against outsiders entering their borders. With the arrival of winter

proof

frosts, the fever usual y disappeared, but in the dead of winter stories began

to circulate again of yellow fever in Tampa. Those reports were denounced

as false and malicious, but proved to be all too true. Once more cities across

the state raised quarantines against their neighbors. Jacksonville suffered by

far the worst, with 430 people there succumbing to the disease. As a result,

the incoming governor, Francis P. Fleming of Jacksonville, called a special

session of the state legislature in 1889 to establish a State Board of Health.

Although the Independents had been defeated in 1884, their spirit lived

on. In 1887, anticorporation feelings found expression in the creation of a

three-man railroad commission appointed by the governor to investigate,

set rates, and prohibit railroads from discriminating among shippers. The

railroads opposed the commission, saying it violated sound economic prin-

ciples and discouraged investment in the state. In 1891, the state legislature

abolished the commission.

Farmers made an effort to organize so they could promote their own wel-

fare. The Grange, a national organization, established branches in the state

in the 1870s. Their appeal was mainly to traditional small farmers growing

crops such as cotton that were suffering from declining market prices. The

Grange urged farmers to stick together and cooperate in buying and selling.

288 · Thomas Graham

The Grange maintained a policy of staying out of politics, but the Farmers

Alliance, which entered the state in 1887, did not. Rather than form a politi-

cal party, the Alliance drew up a list of principles and endorsed politicians

who agreed to support the Alliance platform. By 1890, most Democrats had

pledged their support to the Alliance.

In December 1890, the national convention of the Farmers Alliance met

at Ocala. They adopted the “Ocala Demands” that asked for stronger regula-

tion of the railroads, free coinage of silver, a graduated income tax, election

of U.S. senators directly by the voters, and other reforms. The Alliance soon

disappeared as an organized movement, but the nationwide economic de-

pression of the 1890s increased the discontent of farmers.

Conservative leader Wil iam Bloxham returned as governor in 1897. Pro-

gressives, however, scored some victories. In 1897, the legislature established

a new, more powerful railroad commission. By this time the frantic rate of

railroad building was mostly over. The state’s rail system was reaching a state

of maturity, and even many business interests saw the desirability of govern-

ment supervision.

In another victory, the reformers enacted a primary election method of

nominating party candidates. This took the nominating power out of the

hands of the party elite and meant that men from all parts of the state stood

proof

a chance of winning nomination for governor. Since by this time the Re-

publican Party had become powerless due to the decline in black voting, the

Democratic primary election virtual y decided who would hold office.

Cuban rebellion against Spanish colonial rule resumed in the early 1890s.

Many Cubans lived in Florida, working in cigar factories, and Florida had

other connections to Cuba through investments, cattle sales, and tourism.

José Martí and other exiled rebel leaders traveled frequently in Florida en-

listing support and smuggling arms to Cuba. Napoleon Bonaparte Broward

of Jacksonville gained fame by running guns to Cuba with his tugboat, the

Three

Friends

.

When the United States declared war against Spain following the sink-

ing of the battleship

Maine

in Havana harbor on February 15, 1898, Florida

played a large part in the conflict. Tampa was selected as the primary point

of assembly for a U.S. invasion force. Plant’s Tampa Bay Hotel served as

headquarters for the officers. (Teddy Roosevelt would later brag that he had

camped in tents with his Rough Riders, but he also spent some time in the

hotel with his wife.) The government dredged the harbor channel deeper, an

improvement that would benefit the port after the war. Army camps became

a bonanza for local businessmen and laborers, not only in Tampa but also in

The First Developers · 289

Jacksonville, Fernandina, and Miami, where troops were also stationed. Key

West served as the navy’s closest base to the scene of the conflict in Cuba.

Twelve units of local Florida militia were organized into the First Florida

Regiment, but were never sent to Cuba. Most of the casualties in the war

came from typhoid contracted in camp, not Spanish rifles. United States

authorities feared an outbreak of yellow fever, but none occurred.

Florida gained publicity from newspaper coverage of the war and from

soldiers returning North with stories of their time in Florida. A second ben-

efit from the war came with the discovery of the cause of yellow fever. While

stationed in Cuba, Major Walter Reed performed experiments that proved

yellow fever microbes were transmitted by mosquito bites. With Reed’s dis-

covery, Floridians launched a war on mosquitoes. Final y, northerners could

settle in Florida rather than just visiting during the winters. Florida’s rate of

population growth increased after the turn of the century.

With the return of economic prosperity, America entered a period of

progressive reform. William S. Jennings, cousin of the populist Democratic

presidential contender Wil iam Jennings Bryan, was elected governor in

1900 on his promise to fight special interests. He attempted to prevent the

railroads from taking possession of state lands that had been promised to

them. The railroads sued, but ultimately failed to acquire much of the land

proof

they thought they deserved.

As the end of his term as governor approached in 1904, Jennings threw

his support to another progressive, Napoleon B. Broward, who won with a

promise to drain the Everglades, sell the reclaimed land for settlement by

Floridians, and use the profits to fund the government. “The railroads are

draining the people instead of the swamps,” was his battle cry.7

Once in office, Broward found little support for his proposal to drain

the Everglades because the legislature was reluctant to appropriate funds.

Instead, it voted for a constitutional amendment to create a drainage tax dis-

trict to fund the plan. Without waiting for the public’s action on the amend-

ment, Broward, on July 4, 1906, sent a dredge off from the north branch

of New River in Ft. Lauderdale to excavate west and north toward Lake

Okeechobee.

In November, the voters overwhelmingly rejected the amendment autho-

rizing a drainage tax. Shortly thereafter, Broward began working out com-

promises with the railroads and other corporations to settle lawsuits and

clear the way for new land deals. It also became clear that the two dredges

Broward had in operation were not making substantial progress in lowering

water levels, so Broward constructed two more dredges to join the work.

290 · Thomas Graham

Prohibited by the constitution from running for governor again, Broward

turned the drainage of the Everglades over to his successor, Albert Gilchrist.

During the latter’s administration, the state continued to make settlements

with claimants in the lawsuits over land grants and actual y began to collect

a drainage tax at a lower rate. By this time, it had become clear to every-

one that lowering water levels in the Everglades was a much more complex

problem than it had first appeared.

Yet a great endeavor had been set in motion that would not stop for

generations. Very little concern was shown at the time for the questions

raised by modern-day conservationists. Both progressives and conserva-

tives agreed that draining the big swamp was a good idea.

During his time in office, Broward realized that the citizens in modern

times needed more education than they had been receiving in their back-