The History of Florida (88 page)

Read The History of Florida Online

Authors: Michael Gannon

Tags: #History, #United States, #State & Local, #Americas

portionment system that ensured the region’s control until the late 1960s,

when the courts ruled that both houses of a state legislature had to be ap-

portioned based on population size—the “one person, one vote” principle.

Florida Politics · 419

The Early Twentieth Century: Segregation Clashes with

Development Demands

Throughout the period from 1900 to 1940, state politics were dominated by

a few central issues. National developments, especial y those that occurred

within the Democratic Party, occasional y impacted state politics in sig-

nificant ways throughout this era from the age of progressivism to the New

Deal. Race was never far from the forefront of state politics and played a

particularly prominent role throughout the era from 1900 to 1924.

Development and who would determine its course in the state were other

dominant concerns in the first decade of the twentieth century. Progressive

Democrats like Wil iam Jennings (1901–5), Napoleon Bonaparte Broward

(1905–9), and Broward’s successor, Albert Gilchrist (1909–13), control ed

the governor’s office, but because of their limited ability to carry out their

economic reforms and sharp divisions within the legislature, they gradual y

yielded power to more entrenched, conservative forces in the state.

The opponents of progressivism and even some of its allies believed that

a cheap land policy and private development, even in areas as environmen-

tal y sensitive as the Everglades, were essential to the state’s emergence from

poverty. At this stage in Florida’s development, environmental concerns

proof

took a distant second place to concerns about economic growth and ex-

pansion of the population. Florida’s flirtation with progressivism was thus

a short-lived affair, and by 1912 political power had fallen into the hands of

pro-business spokesmen.

By the end of World War I, land developers had descended upon Florida.

With the rise in popularity of the automobile, it became commonplace for

people to vacation in Florida. Many tourists stayed on, and developers even

sold land sight unseen to northerners persuaded by fantasy advertisements.6

The gradual involvement in the war effort and the social dislocation that

resulted from mobilization caused considerable consternation in the South

over race relations. Having recently imposed segregation, white southern-

ers by 1914 were in no mood to have this system altered. By contrast, black

southerners viewed the war as an opportunity to cast off the oppressive

blanket of segregation by demonstrating their patriotism.

Racial patterns in the South were additional y complicated by the mas-

sive migration of African Americans to the Midwest and Northeast begin-

ning around 1910 to escape the oppression of segregation and the economic

havoc created by the boll weevil’s devastation of the cotton crop. They were

also drawn to the North by the promise of economic opportunity and

420 · Susan A. MacManus and David R. Colburn

proof

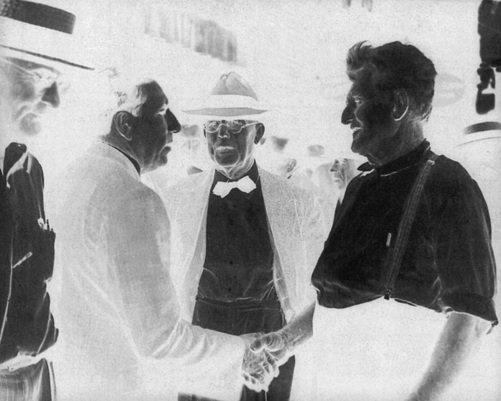

Governor Sidney J. Catts (1917–21) is shown here (

seated, left front

) with his family on the

Governor’s Mansion steps. A resident of Florida only five years when he announced for

governor, Catts campaigned in the rural counties as an anti-Catholic demagogue. Yet

his administration was characterized by numerous progressive programs, including

the penal reform, support for organized labor, and improved status for women. And

his official stance toward Catholicism was conciliatory (his executive secretary was

Catholic, and his son Rozier, with his father’s blessing, married a Catholic).

greater freedom. Labor agents from northern industries and railroads de-

scended on the South in search of black workers.

As the massive exodus of African Americans continued from the north-

ern counties of Florida during the war years, Governor Park Trammell

(1913–17) and his successor, Sidney J. Catts (1917–21), essential y ignored it.

Trammel , no friend of black Floridians, had disregarded the lynching of

blacks when he was the state’s attorney general and during his governorship.

Florida Politics · 421

When the NAACP complained about these lynchings, Catts denounced the

organization and blacks general y.

Catts changed his tune when white business leaders, especial y in the

lumber and turpentine industries, began to complain that the continued

outmigration of blacks was having a devastating effect on labor availability

and labor costs in Florida. Suddenly, Catts urged blacks to stay in Florida

and called for unity and harmony among the races. Few black citizens lis-

tened to him or were intimidated by threats of violence. The migration con-

tinued to escalate as a quiet protest against racial conditions in the South.

During the early 1920s, white Florida gradual y suppressed the aspira-

tions of its remaining black population. Its governors played a willing hand

in this process. They defended their actions by asserting the inferiority and

dependence of the black race and received ample encouragement from the

writings of anthropologists and popular authors who claimed that scientific

evidence documented black inferiority. Black citizens, however, resisted

efforts to reimpose segregation by whatever means were at their disposal.

In Ocoee, black residents marched to the polls in an effort to vote, only

to be physical y assaulted and to have their homes and property seriously

damaged.7

The white commitment to maintaining segregation knew few bounds,

proof

however. In Perry and Rosewood, blacks were killed and their property de-

stroyed fol owing al eged assaults upon white women. When blacks in Rose-

wood tried to defend themselves against a white mob, their public build-

ings, churches, and homes were burned to the ground, six were reported

murdered, and all were chased from the community in January 1923, never

to return.8 The promise of the war years and the great migration had been

completely snuffed out in Florida by 1924, and state leaders were willing ac-

cessories in this process.

Although Catts and his allies remained political factors throughout the

1920s, the Democratic Party returned to the hands of party stalwarts in 1920

with the election of Cary Hardee (1921–25), who took office just in time to

bask in the prosperity of the economic boom in south Florida. The eco-

nomic development and population expansion that Florida had long sought

began to stir, and Florida’s leaders turned their backs on Catts and his al-

lies and eagerly embraced the new investors. Unfortunately, like al rol er

coasters, Florida’s economy suddenly lurched downward in late 1925 when

the land bubble burst, money and credit ran out, and banks and investors

abruptly ceased trusting developers. State leaders had done little to regulate

speculators or to restrain the massive expansion.

422 · Susan A. MacManus and David R. Colburn

The Depression: Fiscal Battles, Taxes Dominate State Politics

Florida became a metaphor for the boom and bust years of the 1920s, and no

state experienced the highs and lows any more thoroughly. By the time the

stock market col apsed in the fall of 1929, Florida was already mired in four

years of depression.9 The financial col apse paralyzed political leaders and

left the state unprepared to meet the crisis. During this period, conserva-

tive campaign slogans, such as “no new taxes” and “make government run

more efficiently,” emerged. They became powerful political ral ying cries for

decades to come.

Governor Doyle Carlton (1929–33) attempted to counter the political in-

eptitude by urging the legislature to raise taxes to reduce a state deficit of

$2.5 million and to assist counties in paying off their bonds. He also sought

a gasoline tax to pay for roads and to keep schools open. But the gover-

nor’s tax plan encountered stil stiff opposition from representatives whose

proof

Senator Claude D. Pepper greets some of his Florida constituents in the 1940s. A vig-

orous advocate of President Roosevelt’s New Deal, Pepper brought many millions of

federal dollars to Florida during the Depression and war years. In his last years, as a

member of the U.S. House of Representatives, he became the nation’s staunchest ad-

vocate for senior citizens.

Florida Politics · 423

counties had small debts and who felt they were being forced to pay for the

sins of those with large debts. At one point Carlton, total y exasperated,

pleaded with legislators, “If the program that has been offered does not meet

with your liking, then for God’s sake provide one that does.”10

Carlton’s successors, David Sholtz (1933–37) and Fred Cone (1937–41),

refused to follow Carlton’s controversial lead. Both blamed Florida’s prob-

lems on irresponsible leadership and called for a return to fiscal restraint,

balanced budgets, and sound business principles. Decimated by the state

and national depression, Florida looked to the federal government more

than most states did for assistance.

Roosevelt’s election and his New Deal programs provided the lifeline

that kept Florida afloat during the 1930s. The Agricultural Adjustment Act,

in particular, provided crucial assistance for financial y desperate farmers

and grove owners. For many, it was not enough. Florida continued to suffer

greatly during the Depression, and as late as 1939 no end seemed in sight.11

World War II: Growth Begins, Tourism Takes Off, Fights for Political

Power Intensify

World War II reinvigorated Florida. The state became a training center for

proof

troops, sailors, and airmen of the United States and its allies. Highway and

airport construction was accelerated so that, by the war’s end, Florida had

an up-to-date transportation network ready for use by its citizens and by the

visitors who seemed to arrive in an endless caravan.12

Led by Governor Spessard Hol and (1941–45), Florida worked closely

with the Roosevelt administration and the War Department to secure

federal funds for Florida. Hol and’s successor, Governor Mil ard Caldwell

(1945–49), dramatical y expanded activities of the Florida Department of

Commerce to attract new business and visitors into the state. Commerce

Department employees seemed to take particular pleasure in sending pho-

tographs of beautiful young women, scantily clad and lounging round a

pool or at the ocean, to northern newspapers in the dead of winter.

Caldwell and his successors also began a series of trips to the North and

Midwest in an effort to recruit more business. Florida’s sales pitch to pro-

spective business interests and residents emphasized low taxes, a healthy

environment, cheap land, and a pro-business political climate. These trips

expanded in subsequent administrations to include foreign countries as

Florida sought to internationalize its economy and its tourism. The state

modernized its roads to accommodate increasing automobile traffic, and

424 · Susan A. MacManus and David R. Colburn

Caldwel ’s successor, Governor Fuller Warren (1949–53), pushed through a

fence law to keep the cattle from crossing the roads, killing the tourists, and