The History Buff's Guide to World War II (45 page)

Read The History Buff's Guide to World War II Online

Authors: Thomas R. Flagel

The Allies also practiced greater economy of effort compared to the Third Reich. As the Soviets concentrated on producing two basic kinds of tanks of relatively simple design, the Germans experimented with dozens of tank versions, making hundreds of prototypes and tinkering with thousands of modifications for each one. While Americans had the versatile jeep, Germans made one hundred dissimilar models of motorcycles. By the end of the war, Americans could produce fifteen B-17s in fewer man-hours than the Germans took to construct a single Tiger tank.

132

U.S. production easily outpaced the whole of the Axis, demonstrated here by the efficient assembly line manufacture of B-17 bombers.

Of all the manufactured goods produced in the world in 1945, half were made in the United States.

3

. COORDINATION BETWEEN COUNTRIES

Born out of propaganda from both the Allied and Axis camps, the image of a unified German-Italian-Japanese war machine contained marginal basis in fact. Aside from mutual hostility toward international Communism and the British Empire, the three main Axis states shared little during the course of the war.

In the summer of 1939, while Japan fought the Soviet Union in a series of increasingly bloody battles along the Manchuria-Mongolia border, Hitler’s foreign office secured the N

AZI

-S

OVIET

P

ACT

. In 1941, weeks before Hitler planned to invade Russia, Japan agreed to a five-year Soviet-Japanese Neutrality Pact. Japan never signed the “Pact of Steel” agreement of mutual assistance penned in May 1939 between Germany and Italy.

It is also fair to say that the Allies had their own divisive issues. There were personality clashes, particularly between British commander Bernard Montgomery and almost everyone else. There were strategy disagreements, such as where and when to invade Western Europe. Yet the Allies generally coordinated their efforts through numerous military and political conferences, plus several major summit meetings including T

HERAN

, Y

ALTA

, and Potsdam. Churchill himself traveled to four separate continents to confer with other heads of state. In contrast, Germany and Japan never conducted a single high-level exchange during the course of the war.

Indicating how little they communicated with each other on major issues, Imperial Japan viewed Hitler’s invasion of the Soviet Union the same way Hitler viewed Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor—with complete and utter surprise.

4

. ACCESS TO RAW MATERIALS

Within their peacetime borders the Axis possessed limited amounts of the materials needed to wage war. Italy led the world in the supply of mercury, used in detonating explosives. Germany was number one in the production of potash, which made fertilizer. Otherwise, resources were scarce.

133

Among Axis leaders, this dearth in raw materials compounded a sense of vulnerability and added to the incentive for regional conquest. At the time, Malaya held almost half of the world’s rubber supply and a quarter of its tin. Most titanium ore came from India or Norway. China and Burma owned the largest known deposits of tungsten, a vital alloy component of armor. France possessed considerable bauxite for aluminum production.

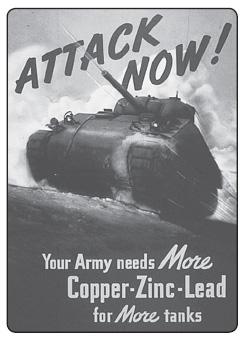

Most of the earth’s coal, copper, lead, nickel, sulfur, and zinc were deep within Allied territories. In one resource the Allies were completely dominant, creating an expression among the Japanese: “A drop of petrol is a drop of blood.”

134

In 1940 the United States accounted for two of every three gallons of gasoline made in the world. Of the Axis, only Romania possessed a large number of wells, and the Germans had no efficient way to transport or process the oil the Romanians produced.

135

When Japan’s oil reserves began to run dry in 1943, the military greatly reduced pilots’ training, making them easy targets against well-practiced Americans. By 1944 the Imperial Navy found itself disengaging or avoiding fights altogether for lack of fuel. For the Wehrmacht, worn-down tanks began to drink oil five times faster than before. In February 1945, the Luftwaffe had only enough aviation fuel to keep fighting at full capacity for two more weeks.

136

By the end of the war, when the United States produced millions of barrels a day, Germany procured only a few thousand a week, most of it “synthetic oil” slowly and expensively extracted from coal. Japan began converting cars, buses, and ambulances to run on charcoal, and its military experimented with a fuel made of alcohol and turpentine.

137

Petroleum haunted Axis leaders right to the end. The bodies of Mussolini and his mistress were hung upside down at a Milan gas station. Hitler wanted to be cremated after his suicide, but there was not enough fuel available to complete the job.

5

. TECHNOLOGY

Initially behind on a number of engineering fronts, the Allies eventually attained superiority in aeronautics, radar, sonar, ballistics, medicine, nutrition, and radio communication. Among their innovations were the proximity fuse, demagnetized ship hulls, synthesized quinine, a predecessor to the computer, and thermonuclear weaponry. The Allies simply had more money, more engineers, and safer work facilities than the Axis.

In contrast, only Germany made significant strides in technology, some of which were revolutionary. Yet advancements were largely negated because the Third Reich failed to emulate the Allies in teaming scientists with soldiers.

Traditionally, the German scientific community depended more on individual genius than teamwork to achieve its breakthroughs. Similarly, the German military tended to be conservative and closely guarded against intrusion. Barriers to cooperation remained through most of the war, resulting in slow response times to serious problems and impressive but impractical innovations.

Examples of this are endless. The Luftwaffe lacked a quality bombsight. Rather than coordinate with engineers to make a better aiming device, the air force demanded stronger wing construction so aircraft could withstand the strain of dive-bombing. Technicians designed the sleek and fast Messerschmitt 262 jet with low-slung engines that sucked up dirt and debris on takeoff. It proved to be a bit of a problem since most combat airfields were unpaved. V-rockets, though impressive to watch, were too inaccurate for any tactical application. In the entire war, there was only one documented case of a direct conference between a German field commander and a team of scientists.

138

Meanwhile, the Allies perfected “Operational Research,” in which engineers studied military equipment in the field to measure performance and seek areas of improvement. Both the British and American leadership had scientific advisers. The Allied apex of achievement was undoubtedly the Manhattan Project, in which tens of thousands of individuals, working in tightly controlled environments at more than a dozen locations, went from abstract subatomic theory to a working device in three years. (Whether that was a good thing is open for debate.)

During the Battle of Britain, RAF Spitfires were able to boost engine performance 25 percent through the use of an American invention: 100-octane gasoline.

6

. POPULATION

Before the industrial revolution, population equaled power. Afterward, industrialized countries gained a considerable edge in business, diplomacy, and military engagements. Yet in a war of attrition, numbers still counted.

For every person in an Axis uniform, there were nearly three Allies. For every civilian in an Axis state, the Allies had five. The Soviet Union alone had more people than Germany, Italy, and Japan combined.

This supremacy in numbers provided two profound advantages: the Allies could replace military losses faster than the Axis, and the Allies could commit larger numbers to logistics and manufacturing. Wherever there were shortages, the Allies were generally more willing to employ women, such as in heavy industry and agriculture, than were the more gender-traditionalist Axis states.

One statistic in particular illustrated which side was more capable of enduring a battle of attrition. Overall, the Allies lost twice the number of combatants as the Axis and still achieved victory.

“Providence is always on the side of the last reserve.”—Napoleon Bonaparte

7

. INTELLIGENCE

Knowledge is power, and through spy networks, reconnaissance, and resistance movements, the Allies knew more and gave away less than the Axis.

The largest disparity came by way of code. The United States made considerable strides in decoding Japanese diplomatic and naval messages. The British, with considerable help from Polish and French operatives, were able to decipher large portions of German communications, especially those of the Luftwaffe.

Both the Japanese and Germans believed their systems were unbreakable, and considering the complexity of the setups, their assumptions were not unreasonable. Both the main Japanese enciphering machine (based on phone switches) and the German “Enigma” machine (based on electromagnetic rotors) produced nonrepeating letter patterns that had possible combinations numbering in the trillions. Even when letters were correctly deciphered, the words they formed were in code, and their meanings varied between agencies. German enciphering was also based on alterable key systems, which changed monthly, weekly, and sometimes daily.

139

Yet the Americans were able to fabricate a Japanese enciphering machine without ever having seen one, and the British procured several captured or copied Enigma machines. With the work of military personnel, translators, etymologists, mathematicians, statisticians, chess champions, and others, the Americans and British were able to uncover numerous vital pieces of information. The greatest breakthroughs provided Luftwaffe combat strength in occupied France, the time and place of Japan’s attack on Midway, disposition of U-boat wolf-pack patrols in the North Atlantic, and the flight itinerary of Japanese navy commander in chief Adm. Yamamoto Isoroku, whose plane was subsequently ambushed and Yamamoto killed.

140

For security reasons, the Allied governments waited until the 1970s to reveal that they had broken Axis codes. The news shocked many former Axis cryptologists.

8

. GEOGRAPHY

Although their war performances differed greatly, the Soviet Union and China shared a weapon that helped them stave off defeat: land. Attacked from one direction, both states were able to relinquish territory and not be overtaken, both were able to transfer large numbers of people and machinery to hinterlands, and both were subsequently able to endure long strings of losses without being totally overrun. Such luxuries were not available to less sizable countries such as Belgium and Singapore.

Japan and Great Britain possessed the advantage of being sizable island states shielded by wide bands of water and functioning as giant and unsinkable aircraft carriers. As it turned out, neither one would be invaded during the war. But their natural barrier also made both countries dependent on shipping for material survival. In this regard, Britain eventually secured the assistance of the United States, while Japan stood completely isolated from its nearest advocate, separated by oceans and land masses in either direction.

Well-suited for the defensive, Italy had limited offensive potential, with its navy bottled in the Mediterranean by the Suez Canal and Gibraltar and its army simultaneously shielded and dangerously separated by its mountainous terrain. Of all the major powers, Germany was probably the most vulnerable, situated between its declared adversaries. Aside from the Alps to the south, it also possessed almost no natural barriers.