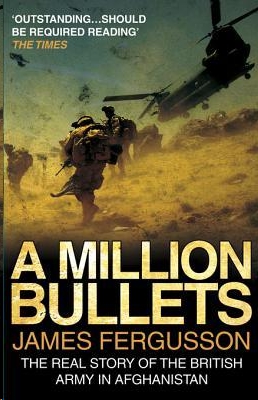

A Million Bullets: The Real Story of the British Army in Afghanistan

Read A Million Bullets: The Real Story of the British Army in Afghanistan Online

Authors: James Fergusson

Tags: #History, #Europe, #Great Britain, #Middle East, #Military, #Afghan War, #England, #Ireland, #United States, #Modern (16th-21st Centuries), #21st Century

Table of Contents

- About the Author

- Title Page

- By the Same Author

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- Chapter 1 In Kandahar

- Chapter 2 Aya Gurkhali!

- Chapter 3 The Dragon's Lair

- Chapter 4 The Joint UK Plan for Helmand

- Chapter 5 The Chinooks Push the Envelope

- Chapter 6 Apache: A Weapon for 'War Amongst the People'

- Chapter 7 Tom's War

- Chapter 8 The Royal Irish and the Musa Qala Deal

- Chapter 9 Amongst the Taliban

- Footnotes

- Postscript

- Notes

- Appendix Maps

- Picture Credits

- Index

James Fergusson

is a freelance journalist and author who began reporting on Afghan affairs more than twelve years ago. His first book, the acclaimed

Kandahar Cockney

, told the story of his friendship with Mir, an Afghan asylum-seeker in London. From 1999 to 2001 he worked in Sarajevo as a press spokesman for OHR, the organization charged with implementing the Dayton peace accord that ended Bosnia's civil war in 1995.

A MILLION BULLETS

Also by James Fergusson

Kandahar Cockney

The Vitamin Murders

A MILLION BULLETS

The Real Story of the British Army

in Afghanistan

James Fergusson

This eBook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author's and publisher's rights and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

ISBN 9781407033822

Version 1.0

TRANSWORLD PUBLISHERS

61-63 Uxbridge Road, London W5 5SA

A Random House Group Company

www.rbooks.co.uk

First published in Great Britain

in 2008 by Bantam Press

an imprint of Transworld Publishers

Copyright © James Fergusson 2008

Maps © HLStudios, Long Hanborough, Oxon

Extract on p. 134 from the First World War version of the song entitled 'We'll Never Tell Them' by Jerome Kern, from the play

Oh! What a Lovely War

by the Theatre Workshop.

James Fergusson has asserted his right under the Copyright, Designs

and Patents Act 1988 to be identified as the author of this work.

This book is a work of non-fiction. In some limited cases names of people, places, dates, sequences or the detail of events have been changed solely to protect the privacy of others and for reasons of operational security. The author has stated to the publishers that, except in such minor respects not affecting the substantial accuracy of the work, the contents of this book are true.

A CIP catalogue record for this book

is available from the British Library.

ISBN: 9781407033822

Version 1.0

This electronic book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, resold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publisher's prior consent in any form other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser

Addresses for Random House Group Ltd companies outside the UK

can be found at:

www.randomhouse.co.uk

The Random House Group Ltd Reg. No. 954009

For Melissa

Acknowledgements

The project could not have gone ahead without the approval of Brigadier Ed Butler, commander of 16 Air Assault Brigade in 2006. I am indebted to him, as well as to Colonel Ben Bathurst and his team at the Public Relations Directorate in the Ministry of Defence.

My thanks also to Susan Aird, Colin Ball, Jane Bonham Carter, Chloe Breyer, Rupert Chetwynde, Tim David, Adam Fergusson (both of them), Robert Fox, Phil Goodwin, James Hanning, Tania Kindersley, Alastair Leithead, Tif Loehnis, Anthony Loyd, David Loyn, Flora Maclay, Jenny McVeigh, Martin Melia, Peter Merriman, Gulalai Momand, Dave Muralt, Ian Nellins, David Ramsbotham, Simon Reade, William Reeve, Chris Riley, Toby Smart, Edward Smyth-Osborne, Rory Stewart, 'Stonker', Miriam Swift, Ray Whitaker, Piers Wickman, Doug Young and all at Transworld – and to all those whose names for one reason or another I cannot mention.

I heard so many extraordinary stories from the troops who took part in Operation Herrick 4 that it has not been possible to tell all of them here. My main purpose in writing this book was, and remains, polemical; it was never intended as an exhaustive history. But to Nick Wight-Boycott's Pathfinders, Gary Wilkinson and the men of 7 Para RHA, the OMLT officers and all the others whose voices I know also deserve to be heard, I apologize.

Finally, I am deeply grateful for the cooporation and understanding of the families of the killed, not all of whose names appear in these pages. A percentage of the profits from this book will go to Combat Stress, the ex-Services mental welfare society.

Introduction

The war had been running for more than a month before the public properly woke up to it. It was not until early July 2006 that the first images of the fighting in Helmand began to filter on to our television screens. In retrospect it is clear that the news had some serious competition that summer, the hottest in Britain since records began in 1772. Those still indoors were mostly tuned either to

Big Brother

, the seventh series of which had begun in May (the competition was eventually won by Pete Bennett, a ketamine addict from Camberwell who suffered from Tourette's Syndrome), or, more likely, the closing stages of the World Cup in Germany. (England was knocked out by Portugal on 1 July after a penalty shoot-out. The final eight days later, won by Italy, attracted an estimated global audience of 715 million people – the mostwatched event in television history.)

Yet even for those paying attention it was hard to make out what was going on in Helmand – or 'Hell Manned' as the BBC persistently called it. Chinook helicopters touched down in violent sandstorms of their own making. Hoarse squaddies, their tattooed arms and chests exposed to the burning desert sun, dropped mortars into firing tubes with the speed and precision of robots on a production line. They crouched behind sandbagged machineguns that spat torrents of tracer fire, or zig-zagged towards mud buildings and an unseen enemy to a soundtrack of explosions, curses and heavy breathing.

Our senses were tantalized. As the news anchors solemnly explained, most of the 'unique footage' on our screens had been filmed by the troops themselves. This sounded almost like a coded apology for the poor quality of the clips, which tended to be short, jerky and badly pixelated. And though the names of the battlefields changed – Now Zad, Sangin, Musa Qala, Kajaki – the crash-bang footage soon took on a disturbing sameness. As viewers we relied on the presenters to impose any sense of continuity or rationality. We could see that a military crisis was unfolding on the other side of the world, yet the more we watched, the less the pictures seemed to offer an explanation of how or why this was happening.

One thing, at least, was clear: there were many members of the Armed Forces who would be missing the World Cup Final. This was not some blip in a benign peace-keeping campaign that we were watching, but a full-blown battle. The British, it seemed, were cut off and under siege in at least three southern Afghan market towns, manning the sangars

*1

of fort-like local government district centres – or 'platoon-houses' as they were sometimes known – against a well-armed enemy determined to throw them out. Rorke's Drift came to mind. It was as though a whole new front in the War on Terror had opened up while we were looking the other way. General David Richards, the British commander of ISAF, Nato's International Security Assistance Force in Kabul, later appeared to confirm our groggy impression. The military, he said, was engaged in the most 'persistent, low-level dirty fighting' undertaken by the British since the Korean War, half a century ago. A professor at the Royal Statistical Society declared that British soldiers in Afghanistan were precisely six times more likely to be killed than their comrades in Iraq.

My concern was personal. As a journalist I had been reporting on Afghanistan for over a decade. My first book,

Kandahar Cockney

, documented the travails of Mir, a Pashtun interpreter with whom I once worked, and whose family I helped to gain political asylum in London in 1998. We are still close friends. Yet it now looked, dispiritingly, as though our two countries were at war again for the first time since 1919. The potential consequences of this renewed fighting, both for our friendship and for the peace and security of the country he loved and to which he and his family fervently hoped one day to return, were serious.

My feelings were further complicated by indirect family involvement. My wife's cousin Tom Burne, a lieutenant in the Household Cavalry, had been deployed as part of the Helmand battle group. He was twenty-five and had been out of Sandhurst for little more than a year when he was called upon to swap his horse and bearskin for the turret of a Scimitar light tank. Tom was tall, fair-haired and good-looking. We had recently spent Christmas with him in New York, at the home of his marketing-director sister. He was a sunny, easy-going person, the kind who laughed so often that he seemed almost impervious to the troubles of life. I recalled his free-wheeling gait on a walk through Williamsburg, his red socks and beaten-up loafers scuffing the graffitoed tarmac, his hands stuffed comfortably into his overcoat against the crisp winter air. Williamsburg, a chic but still up-and-coming neighbourhood of Brooklyn, could be mildly threatening at night, but it was no match for Tom, who wore his confidence like a suit of armour. That, like the real armour of his tank, was soon to be sorely tested.

Like everybody else in the battle group, Tom was sent first to Camp Bastion, the British Task Force's £1 billion Helmand headquarters.

Bastion was located deep in the remote Dasht-i-Margo, the poetically named 'Desert of Death'. In a few short months this enormous military base had risen from the empty sands, and now housed thousands of British troops. They had a gym there, and airconditioning, and access to computers with email. Tom and I corresponded, and for a few short weeks he became my inside track on what was going on.

'A pleasure to hear from you, and yes, there is sand in my i-Pod!' he wrote. 'In fact there is bloody sand everywhere!'

I'd written to ask him about a report by Christina Lamb, the

Sunday Times

correspondent, who had recently gone out with a patrol that had been ambushed. Her account had been widely noticed at home, and was an important milestone in the public's growing realization that all was not well in Helmand. Tom had to choose his words carefully for security reasons, yet it was still evident that the situation was actually worse than we knew. The incidents reported in the media were 'the tip of the iceberg', he wrote. 'In reality we are dealing with around three Christina Lamb-type incidents per day.' Morale among the battle group, he reported, was extremely high despite some recent British deaths.

Their mission to win hearts and minds, he said, was not just clear but 'simple', and was being 'successfully received' across the province. He was proud that they had 'not had one collateral damage casualty throughout all the engagements', a result he attributed to the restraint and professionalism of the troops, who had been issued with a 'robust set of Rules of Engagement'.

I admired but did not share Tom's optimism. I was already hearing quite a different story from Mir about collateral damage. Afghan contacts had told him that many innocents were dying. The problem, he said, was not the troops on the ground so much as the Coalition bombers and helicopters flying in their support. Mir was filled with angry gloom. When 1,000lb or 2,000lb bombs are dropped into built-up areas, he reasoned, bystanders were bound to get caught sooner or later. His prediction was tragically accurate. By the end of the year international forces had unintentionally killed at least 320 non-combatants, and Hamid Karzai, the President of Afghanistan, publicly wept as he called on the Coalition to stop 'killing our children'.

Of course, Tom was still acclimatizing at Camp Bastion in July and had yet to see action in the forward areas. It was a relief to learn that he had been assigned a job as a liaison officer, which would no doubt entail some dangerous reconnaissance work but not, his family hoped, the full-on combat of the outstations. His first fortnight in Afghanistan was spent drinking ten litres of water a day – disgustingly warm, he complained, because there were as yet no fridges – and preparing his troop for forthcoming operations. His was a modern mechanized unit that spent long days training and adjusting their vehicles, but some of the camp's offduty activities sounded weirdly Victorian. 'I have been unable to enthuse the locals with a game of cricket,' Tom wrote. 'For some reason they are wary of the outfield on our pitch. Probably the mine tape is keeping them away! However, Afghan ponies have been found so polo could be introduced. The volleyball with the nurses is also something I feel strongly should be a regular thing! Good morale for the boys.'