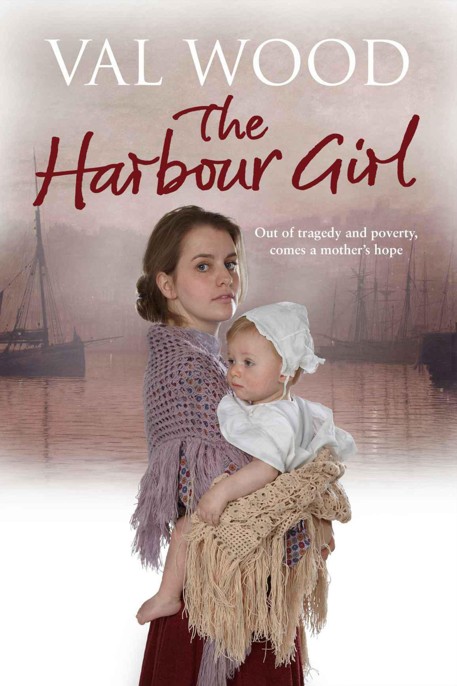

The Harbour Girl

Authors: Val Wood

Tags: #Divorce & Separation, #Family Life, #General, #Romance, #Family & Relationships, #Sagas, #Fiction

| The Harbour Girl | |

| Val Wood | |

| Random House (2012) | |

| Tags: | Divorce & Separation, Family Life, General, Romance, Family & Relationships, Sagas, Fiction |

Synopsis

Scarborough, 1880. Young Jeannie spends her days watching her mother and the other harbour girls sitting at the water's edge - mending nets, gutting herring - and waiting for her friend Ethan Wharton to come in on his father's fishing smack. As she was growing up, Jeannie always expected to marry Ethan, who is loyal and dependable. But then she meets Harry - a stranger who has come to visit from Hull for the day - and she falls for him. He is exciting and irresistible, and seems very keen on her. But he breaks his promise to come back for her, and Jeannie finds herself young, pregnant and feeling very isolated. Jeannie moves to the port town of Hull where her new, difficult life with a child - touched by illness, tragedy and poverty - is often made bearable by the kindness of others. But she finds herself wishing for the simpler times of her past, wondering if she will ever find someone who will truly love her - and if Ethan will ever forgive her...

About the Book

Scarborough, 1880.

Young Jeannie spends her days watching her mother and the other harbour girls sitting at the water’s edge – mending nets, gutting herring – and waiting for her friend Ethan Wharton to come in on his father’s fishing smack.

As she was growing up, Jeannie always expected to marry Ethan, who is loyal and dependable. But then she meets Harry – a stranger who has come to visit from Hull for the day – and she falls for him. He is exciting and irresistible, and seems very keen on her. But he breaks his promise to come back for her, and Jeannie finds herself young, pregnant and feeling very isolated.

Jeannie moves to the port town of Hull where her new, difficult life with a child – touched by illness, tragedy and poverty – is often made bearable by the kindness of others. But she finds herself wishing for the simpler times of her past, wondering if she will ever find someone who will truly love her – and if Ethan will ever forgive her...

Contents

THE

HARBOUR GIRL

Val Wood

To my family with love, and for Peter

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

SPECIAL THANKS ARE due to Dr Robb Robinson who kindly and generously gave me permission to use his informative and interesting book

Trawling: The Rise and Fall of the British Trawl Industry

(Exeter University Press), and to thank him, too, for his patience in answering my ingenuous questions on the subject of fishing.

Also to Jim Porter of The Bosun’s Watch and Chris Pether-bridge’s Hull Trawler site: Hull Trawler – Smack to Stern,

www.hulltrawler.net.

The Scarborough Maritime Heritage website is a most excellent site and I give my sincere thanks to the archivist for allowing me to use the information therein. In particular, I must mention the factual details regarding the Great Storm of October 1880 in which many ships and lives were lost and which I was able to incorporate as part of my fictional story.

CHAPTER ONE

Scarborough, 1880

THE DOOR IN the wall had been bricked up for many years, long before Jeannie was born. There had once been a shop there and the door had been regularly used, but when the shopkeeper died the building was turned into a rooming house and another door opened up, rendering the original obsolete. It had been blocked roughly and hastily and wasn’t level with the wall, leaving a niche about a brick and a half deep, a space just right for a small thin girl to shelter in. From inside this narrow refuge Jeannie could see her mother’s back as she sat deftly mending nets, and watch the harbour.

Had her mother known she was there, she would undoubtedly have told her to go back home to Sandside, or sent her to buy bread or call on Granny Marshall with a message, and Jeannie didn’t want to do any of those things. She wanted to wait for Ethan Wharton to sail into harbour in his father’s fishing smack. Ethan was twelve, four years older than her, and he would know that she was there, watching him, so would make a great show of bringing in the vessel without a scrape and tying up with assumed casualness below the castle hill, close by the warehouses and the boat builders’ slipway.

There she is, she thought, her keen eyes picking out the

Bonnie Lass

as she nosed her way through the waterway, screeching herring gulls following in the wake. Jeannie’s mother turned her head.

‘Jeannie!’ When Mary spoke the name it sounded like Jinnie. She had chosen the name Jeannette, after her own Scottish grandmother. ‘Jeannie,’ she called again, ‘come here. I know you’re there. You can’t hide from me, bairn.’

‘How did you know I was there?’ Jeannie asked from behind her.

‘Ah! Your mother knows everything.’ Mary Marshall looked up from beneath the shawl which covered her red hair to smile at her daughter. ‘Go now and tell Josh Wharton to go home immediately. There’s news waiting for him.’

‘What news?’

‘Never you mind.’ Mary’s eyes went back to the nets. ‘He’ll know. And come straight back; I need you for a message to your gran. Don’t dally talking to Ethan. He’s plenty to do without you bothering him.’

Jeannie opened her mouth to reply, but her mother waved a swift hand so instead she ran barefoot towards the slipway, avoiding the nets and ropes and lobster baskets, to where she could see Ethan, his older brother Mark and their father bent low over their catch.

‘Mr Wharton,’ she piped. ‘You’ve to go home straight away.’

Josh Wharton looked up, pushed back his sea-stained hat and grinned. He said something to his two sons, then stepped quickly off the

Bonnie Lass

and ran to the cliff path, up the narrow streets and alleyways of Sandside towards the cottages clustered below the castle walls, which seemed from down below to be built one on top of another, their red roofs overlapping.

Jeannie walked towards the smack. ‘Hello, Ethan,’ she said shyly.

He nodded, felt for something in his pocket and beckoned her closer. ‘Here.’ He held out his hand. ‘Da said I’d to give you a penny.’

She took it. ‘What’s it for?’

He shrugged. ‘Bringing the message, I suppose.’

‘Why did he have to go home?’

He lifted up a pail and turned his head away, a flush creeping up his neck. ‘To see Ma, I expect. She’s having a babby.’

‘Oh,’ Jeannie said. ‘I didn’t know.’ She was cross that she didn’t know. She would have liked to announce that his mother had been delivered of a baby girl or boy. But maybe that was why her mother hadn’t told her, knowing that she would blurt out the news.

‘Did you get a good catch?’ she asked, and he nodded. They’d gone out last night, when the sea was calm and there was a moon; it would have been a good night for fishing. Not like the night two years ago when her father had gone out and hadn’t come back. She only just remembered him. A Scarborough man born and bred, her mother was proud of saying, as his father and grandfather were before him, though his grandmother, Alice, came from a Hull whaling family.

Jeannie’s mother had been a Scottish fisher lass who had come down from Fraserburgh to Scarborough following the herring fleet; she’d met Jeannie’s father, Jack Foster Marshall, and never went home again. Mary was never short of work: she was swift and sure when mending nets, and during the herring season – between October or November to March – she went back to her old job on the quay, gutting and curing the ‘silver darlings’, and filling and rolling the huge storage barrels. Best of all were the times when the Scottish fisher girls arrived, for her own mother still came with them and Mary could catch up with news from home.

She had not stopped working after the tragedy of losing her husband to the sea, for she had a young family to feed. Jeannie had been only six, a year younger than her brother Tom. Tom wanted to go to sea like his father, and had already been promised a job with a family friend as soon as he was twelve.

If Mary was worried that her son might suffer the same fate as Jack, she never showed it. They were fisher folk, the sea was in their blood, salt in their spittle and seaweed in their hair. There was no other calling.