The Great Fossil Enigma (50 page)

Read The Great Fossil Enigma Online

Authors: Simon J. Knell

In a parallel review, Paul Smith saw Sweet playing the role of devil's advocate: “One does not have to be an orthodox Popperian to conclude that Sweet is here being rather mischievous and is not advancing testable hypotheses.”

29

He wished Sweet had maintained a “more objective viewpoint,” but that was Sweet's point: There was too little that was objective about the British animal and too much that exposed the frailties of interpretation.

Aldridge and Briggs recognized that Sweet's forthright approach had produced a useful and stimulating book with which a new generation of scientist could argue. They had, in effect, begun those arguments in this review. Those arguments would, however, soon fade from view while the book would live on. It would remain on library shelves for decades, just as Lindström's had, there to suggest to outsiders that this was the way things stood.

At the close of the 1980s, Aldridge was in Leicester and Briggs in Bristol. The decade ended with the final dispatching of the first and second contenders for conodont animal. Melton and Scott's animal was redescribed by Conway Morris in a paper that ironically, given the delayed publication of original paper, was lost in press for six years. Possessing considerably more material, Conway Morris was gentle on these earlier authors and celebrated the animal in its own right for its peculiar ecological interest and zoological strangeness. Now Conway Morris could reinvent it as the animal that fed on conodonts. The canard finally had scientific recognition. The first animal was dead.

30

Some, though, looked at the rock in which these fossils had been found and wondered how a conodont-eating animal could exist where there are, inexplicably, no signs of conodont life.

Now it was Conway Morris's turn to suffer the ignominy of error. He had admitted his mistake not long after the Scottish animal had been published, but this did nothing to protect him from a little ridicule. As mistakes go, Gould remarked, Conway Morris had “made a beauty.”

31

Through scientific eyes the path of progress is littered with mistakes, though Gould thought them “not badges of dishonor.” Conway Morris's interpretation of

Odontogriphus

had produced an animal of its time; had he come across it in 1989, he would have read it entirely differently. It was simply a price to be paid. But Conway Morris would, more than most, recognize how long-lived books like Gould's

Wonderful Life

could infect a scientific career. In the ephemeral press of scientific publishing, disproven interpretations are soon forgotten, but

Wonderful Life

kept Conway Morris's past alive, portraying him to readers as the author of outmoded ideas long after he had given them up. When Conway Morris later came to write his own popular book,

The Crucible of Creation

, its reviewer, Richard Fortey, detected the author's loathing of Gould.

32

He accused Conway Morris of selective amnesia and the rewriting of his own history but reflected that Gould's book perpetuated old science and retained Conway Morris as its keeper. One could understand why so many scientists doubted the validity of books. As vehicles by which progress is made, they have the unfortunate effect of producing a freeze-frame image that is then left to drift into the future, giving the illusion of still being current. The scientific book is an impossibility; almost immediately it is a history book.

Eight years after the first true conodont animal had been found, the questions it posed had not been resolved. The animal remained locked in argument. Sweet seemed to imply that Aldridge, Briggs, Smith, and Clarkson had aspirations for their animal, that they had the vertebrates in their sights. Aldridge and company, however, felt that their ideas were simply developing as new data were revealed. Indeed, Clark's constant supply of animals had progressed many of those initially tentative arguments to a point of certainty. When, in 1989, Conway Morris came to review the progress that had been made, he felt sure that the animal was a chordate and that it held tremendous potential for understanding the origins of vertebrates.

33

He also believed that more and better fossils would be found. How wonderfully ironic it would be if, after such a circuitous journey, the animal Pander had dared to imagine became a reality. Of course, there never really had been a circular journey through a hundred possible identities â that was just a myth. Those who knew the conodont â really knew the conodont â knew it had never really left the place where Pander had originally put it, that never-never land where vertebrate meets worm, and where hagfish, amphioxus, and a host of other chordates swim. The conodont animal's natural home was that most difficult and enigmatic of all palaeontological places, that place where vertebrates begin in time and in space. And this was where conodont science was now heading.

“Over the Mountains

Of the Moon,

Down the Valley of the Shadow,

Ride, boldly ride,”

The shade replied â

“If you seek for Eldorado!”

EDGAR ALLAN POE

,

“Eldorado” (1849)

Â

Over the Mountains of the Moon

IN THE MID-1980S, OUT OF SIGHT OF THOSE DEBATING THE

meaning of the first Scottish animals, the next big step was being taken in a part of the world that had thus far proven itself completely lacking in these extraordinary fossils: South Africa. Here, along a dirt road in the Cedarberg Mountains, some two hundred kilometers north of Cape Town, Geological Survey officers Danie Barnardo, Jan Bredell, and Hannes Theron came across a new borrow pit for road metal exposing the soft and rarely seen Upper Ordovician Soom Shale.

1

They stopped to investigate and found their curiosity rewarded with some intriguing fossils reminiscent of graptolites. Graptolites are one of those classic groups of extinct animals all paleontologists study at some point in their training. Tiny, colonial â bearing a passing resemblance to corals and bryozoans â their fossil remains are most common in shales, where they look like minute flattened saw blades. Theron sent a specimen to Barrie Rickards at Cambridge University in the UK, an expert on this group, to see if they really were graptolites. Rickards said they were not.

A number of scientists at the Survey headquarters near Pretoria, including palaeobotanist Eva Kovács-Endrödy, however, became intrigued by the similarity of these new fossils to strange spiny plants found in much younger Devonian rocks. If this was what they were, then these were clearly important finds. In an echo of Pander's conodont discovery, they would push back the origins of plants by forty million years. The oldest plants known at that time came from the late Silurian. Theron and Kovács-Endrödy prepared a paper naming these new plants

Promissum pulchrum

, meaning “beautiful promise.”

2

They did not know that rather than being harbingers of a green and pleasant Eden, these new fossils held a beautiful promise of a rather different kind.

As is the normal course with scientific publication, the paper was sent out for independent external expert opinion. The task of reviewers is to consider a paper's merits and to advise the editors on whether it should be published. On this occasion, one reviewer believed the authors had not demonstrated that these fossils really were the remains of plants but left the decision on publication to the editor. The paper was finally published alongside a reply by the critical referee and a response from the authors.

This discussion mentioned Rickards's view that the fossils were not graptolites, but Rickards was concerned that he had been quoted when he had only seen one specimen. So more material was sent to him by diplomatic pouch and he confirmed his conclusion that they were not graptolites. He thought they looked rather jaw-like and discussed them with several of his colleagues. Together they alighted on the idea that these fossils just might be conodonts. The main problem with this identification was their size; they were more than ten times bigger than the conodonts they were used to seeing. Rather than being up to two millimeters long (though usually much smaller), these were up to two centimeters long!

Rickards knew these fossils crossed the boundary of his expertise, so he contacted Dick Aldridge. Aldridge was intrigued and traveled to Cambridge the next day. It was to be another important day, for here he saw the first conodont specimens known from Africa south of the Sahara and the first complete apparatuses from the Ordovician. And if these were not in themselves major milestones, he could also confirm that they belonged to a giant animal. Preserved merely as molds, Aldridge empathized with the Survey officers who had struggled to identify them. They were, in every sense, conodonts like no others and totally unexpected.

Seeking further confirmation, in August 1987 Theron took some specimens to the Devonian Symposium held in Calgary, where he showed them to a number delegates with expertise in fossil plants and conodonts. They were overwhelming of the view that these fossils were conodonts, albeit of amazing size. Nevertheless, back in Pretoria, Kovács-Endrödy and others remained wedded to the plant and insisted that they continue with the publication of a more extended paper advancing this idea. Theron was, however, now convinced the fossils were conodonts and withdrew as a coauthor, later joining Rickards and Aldridge in publishing a paper identifying

Promissum

as a conodont.

African conodonts, apparatuses, giants â there were many reasons for the South African geologists to welcome the news. They may have lost their landmark discovery of plants, but they had gained something quite extraordinary. Communication lines now opened between Aldridge and the Survey workers, and in 1990 he found himself traveling to South Africa to study their collections of Soom Shale fossils. At the time, all he knew was that there was a wonderful opportunity to progress science's understanding of the animal in this part of the world. Ever since the animal had been found, Briggs and Aldridge, in particular, had been searching for new resources and new ways of looking. Briggs had searched Lagerstätte collections in the United States and now Aldridge did the same in the Soom Shale collections in Pretoria. He also collected some material himself and brought it back to Leicester. It was when he was examining these new finds under his binocular microscope â playing with the lighting to get the best possible illumination â that his eye came across two indistinct oval impressions. Were these those strange, dark-lobed structures he had seen in the Scottish animals? He felt “a buzz of excitement.” Had he chanced upon yet more animals and perhaps â given the relative ease with which apparatuses had been collected â the richest deposit yet? He needed to get back to South Africa â and urgently.

In 1991, with a small research grant in his back pocket, Aldridge returned South Africa to search for the animal with Theron and others. Theron had arranged for the use of a mechanical excavator which had cut a trench into the exposure at the original find site. This produced a heap of rock ready to be split, and on the second day of collecting, August Pedro was holding a complete apparatus in his hands. It had associated with it two ring-like structures. It seems that Pedro had a Neil Clarkâlike talent for finding these fossils, and soon more followed. The Soom Shale was that day understood anew. It too was a Konservat-Lagerstätte, and of an age hardly represented by such deposits. A new window had been opened into the deep past. It had been an important day.

With each new conodont fossil found, Aldridge gained an increasing sense of the three-dimensional structure of the hollow rings: They were deep and inwardly tapering. They did, indeed, seem to be the remains of the animal's eyes. Almost identical circular objects had been seen in the Silurian relative of the lamprey

Jamoytius.

An important animal, in the 1940s

Jamoytius

had been regarded as “undoubtedly the most primitive of the âvertebrate' series of which we have knowledge.” In the 1960s, Alexander Ritchie from the University of Sheffield visited the Scottish site where the original fossils had been found and gathered more and better specimens.

3

He interpreted the distinctive circular rings in these fossils as sclerotic cartilages surrounding the eyeball. These were so like those now found in these new conodont animals that Aldridge and Theron thought this a reasonable interpretation for them.

In total they now had about thirty apparatuses, five of which showed soft tissue preservation. They left the excavation feeling that the shale had more secrets to reveal. There were hints of more complete animals, but they needed less-weathered rock to have any hope of finding them. They remained optimistic and planned for the future â a future that had now shifted geological position. Granton had perhaps said all it was going to say. The latest animals had been reassuringly confirmatory, but none had been better than the first. In October 1991, Briggs, Aldridge, and Smith planned what they thought would be their last paper on the Granton animals.

The South African fossils had given the conodont animal project renewed momentum. In 1992, Aldridge expanded his team in order to populate those edges of the science that seemed to offer greatest potential for advancing the animal. Sarah Gabbott was recruited to research a doctoral degree on the Soom Shale Lagerstätte, and Mark Purnell, who possessed a Natural Environment Research Council fellowship, chose Leicester as the best place to work on element morphology and apparatus architecture. Following the breakup of the Nottingham team, Paul Smith also had moved. In 1990, he had become curator of the Lapworth Museum at the University of Birmingham, where he would lead his own conodont research team. From 1992, he was joined by postdoctoral researcher Ivan Sansom. In that year, then, the British effort had been considerably strengthened and reconfigured. Considered as a whole, it was now by far the largest research group ever to have worked on the animal.

How Dick Aldridge's world had changed. It seemed that luck was perpetually on his side. The first animal discovery had been delivered into his hands by chance and the South African fossils had arrived in a similar fashion, apparently drawn to him by some kind of magnetism. But in both cases, it was Aldridge's swift actions that put him firmly in the picture. There was no magnet; he was simply one of the best known conodont workers in a tiny population of such people in Britain. His involvement in the discovery of the first animal had, however, repositioned him in the field. Who else would one speak to about the biology of this animal other than Briggs, Aldridge, Smith, and Clarkson? Of these, Aldridge was the senior conodont expert. Like other successful conodont workers, Aldridge could spot an opportunity and he was not one to see it pass him by. Like Briggs, he kept his eye on the ball â he knew which directions and which resources were required to negotiate the animal's progress. The conodont animal had by then become central to his scientific being; it was not a subject to dabble in, as so many had. Now the conodont was rather more than it had been. It was knocking on the door of vertebrate ancestry and â as Alfred Romer noted long ago â therefore on the door of human conscience. No longer could it be dismissed as a fine, if arcane and exotically abstract, tool. For so long, its utilitarian value had outshone its biology, but now it seemed that even this might be reversed.

This focused dedication, backed up by considerable ambition and intellectual aspiration, meant Aldridge possessed the best fossils and the best sites and was part of a number of powerful collaborations. Luck did not come into it. The animal, and particularly its vertebrate pretensions, had turned a key. It was now possible to fund research that only a few years earlier would have seemed excessively esoteric. He and his collaborators found themselves on the mailing lists of the popular press and editors of encyclopedias; the British view of the animal was becoming the new orthodoxy â even if contested by some vertebrate paleontologists and other scientists in various parts of the world. This did not, however, leave these others entirely out in the cold, for they could participate by throwing challenges in the path of these British workers, as Janvier delighted in doing. The animal was never a crusade, always a scientific dialogue in which the naysayers had a vital role.

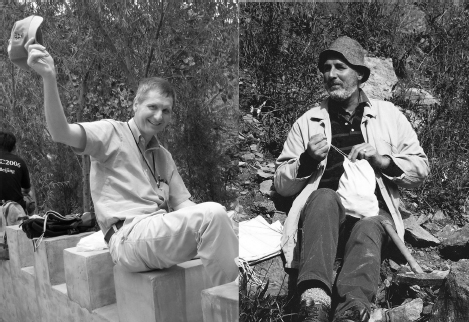

14.1.

Derek Briggs (

left

) and DickAldridge. Photos: DickAldridge.

To establish the vertebrate argument more widely, Aldridge, Briggs, and their collaborators knew they had to be active on all fronts, that the article in the encyclopedia, university newsletter, or popular science magazine was just as important as the basic science. They realized they could not simply “publish and be damned”; they had to fight to hold the territory they had won. But this was no blind political campaign. What they relished was the opportunity to take good science wherever it might lead. They knew that maximum exposure also resulted in new tests, challenges and opportunities, and therefore better science. But even they could not deny that they were empowered in another way, for they formed a relatively large, cohesive, intellectually diverse, support group unlike any in the world. Even they could not deny that they were a force to be reckoned with. Critics looking on, who perhaps preferred a rather different interpretation of the animal, might argue that the science they made was influenced by the vertebrate lens through which they saw their data. These critics could not help but see how “lucky” this group had become.