The Grand Ole Opry (8 page)

Read The Grand Ole Opry Online

Authors: Colin Escott

We had to be on the Opry for the prestige and the publicity, and on the road for our income.

The idea for the Artists Service Bureau began with a trip to west Tennessee for a show over the Independence Day weekend,

1934. The turnout surprised Judge Hay,

.”

who brought along Uncle Dave Macon and several other Opry acts. Almost eight thousand people showed up for the all-day show,

and Hay’s eyes were opened to the potential of the Opry on the road. Open-air picnics were an especially big draw because

admission was sufficiently low to attract Depression-weary farm families.

JUDGE HAY:

The Opry was pretty solid after about ten years, and so was the Artist Service Bureau. The Artist Service Bureau was started

during the last part of 1934, but we didn’t get underway to any appreciable p1ent until the first part of 1935. Very soon,

it was no longer a case of groping in the dark. We had records of the dates played; which act had played it; the amount taken

in at the box office; how large the attendance, etc. Theatre managers, high school principals, promoters of fairs and picnics

called WSM frequently for acts, whereas in the first years we had a selling job to do.

Judge Hay’s role at the Opry and the Artists Service Bureau could have made him into one of the most powerful men in the young

country music business, but personal problems sidelined him, and he took a leave of absence between December 1936 and March

1938. Harry Stone’s brother, David, took over the Artists Service Bureau and assumed responsibility for the Opry’s newest

stars, the Delmore Brothers. The Delmores had come to the Opry in 1933 and were instantly popular. Their two guitars and haunting

sibling harmony wove delicate patterns, quite unlike the boisterous string bands. The earlier Opry acts had come of age in

the pre-microphone era, but the Delmores, like Bing Crosby and the pop crooners, used microphones to produce a much subtler,

nuanced sound. Their musical harmony didn’t spill over into their personal lives, however, and they fought each other and

the Opry management.

ALTON DELMORE of the Delmore Brothers:

We had pulled for David Stone to take Judge Hay’s place as Artists Service manager when Mr. Hay got sick. We thought David

would help us to get someone to play with we could depend on, but we couldn’t get the good ones from the Opry. We had to take

the drunkards and troublemakers and it nearly drove us nuts. We had pulled for David to get the job, but when he got in he

forgot about us, and I learned another lesson in human personality. We’d gotten along real well together until he got the

big job of being our big boss.

The Delmore Brothers, Rabon and Alton.

Trying to keep the Delmores employed, David Stone put them on the road with the Opry’s African American “harmonica wizard,”

DeFord Bailey.

D

E

FORD BAILEY:

They’d stick by me through thick and thin. They was one hundred percent. They watched out for me. “If you can’t feed DeFord,

we can’t eat here, either,” I remember them saying many a time. I usually had to eat in the kitchen, but at least they saw

to it that I got to come in and eat, and not have to set out in the car. If the place wouldn’t let me come in at all, they’d

drive on down the road fifty miles or more to find another place that would. Most of the other performers would bring me a

sandwich to eat in the car, but not them boys.

Judge Hay wrote several booklets and many articles about the Grand Ole Opry, almost never mentioning rival radio barn dances,

like the WLS Barn Dance in Chicago, or competition from hugely powerful American-owned stations just across the Mexican border.

WSM had a five-thousand-watt signal, but the border stations’ five-hundred-thousand-watt signals were so powerful that wire

fences could pick up their transmissions. David and Harry Stone, however, were very much aware of the competition, and fought

it ruthlessly.

ALTON DELMORE

of the Delmore Brothers:

One Saturday night, Harry Stone called us off and whispered to us confidentially, “Boys, I understand that some WLS big shots

[program directors from WLS, Chicago, which hosted the WLS Barn Dance] are coming down np1 week to make you a lot of promises

and tell you a lot of lies. They will be trying to get you to come work on WLS. You have a good future here on the Opry, [and]

I’m raising your pay. You, Alton, will get twenty dollars a week and Rabon will get fifteen. Now don’t have anything to do

with those sons of bitches when they come here np1 week. They just want to pull you away from us because you are so popular.

If you leave, I will never take you on the Opry again. Your career will be ruined.” Four or five weeks later, we were called

into Mr. Stone’s office. “Boys, I have bad news for you. We’re gonna have to cut you back to the regular rate for Opry entertainers.”

That was five dollars a week each.

Edwin Craig and Harry Stone were sufficiently concerned about the five-hundred-thousand-watt border stations and fifty-thousand-watt

Ameri-can stations to lobby the Federal Communications Commission for an increase in WSM’s wattage. Most fifty-thousand-watt

stations were allocated a “clear channel,” so that no other stations could broadcast on their frequency.

JACK D

E

WITT, WSM’s

chief engineer:

In 1931, WSM got permission to go to fifty kilowatts [fifty thousand watts]. In the daytime, the fifty kilowatt is a ground

wave and it’s steady. It reached about twohundred miles. At night, the ionosphere reflects the skywaves to great distance,

so WSM could be heard eight hundred to a thousand miles away, but it’s always a fading signal, slightly intermittent due to

the ionosphere moving around. I’d been a part-time engineer [at WSM in 1925–1926] and I rejoined the station in March 1932

as chief engineer. We went to fifty thousand watts in November that year.

Jack DeWitt: “Originally, we had a five-hundred-foot tower that a bridge company built, and that had trouble, so we made a

contract with Blaw-Knox to build a transmitter in Brentwood. It was designed by a Chinaman at MIT. I couldn’t get him to let

me pay him for I finally sent him a check for fifteen hundred dollars, and he told me it made an alcoholic out of him.” The

new tower was completed in 1932, the year WSM went to fifty thousand watts.

left: WSM’s Tower under construction.

right: A souvenir postcard of the completed WSM tower.

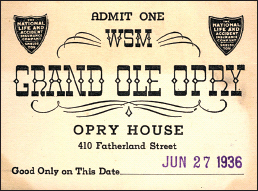

The increased wattage took the Opry from the Rockies to the Caribbean, and that in turn brought many more people to Nashville

to see the show. After less than two years at what is now the Belcourt Theatre, a larger venue was required, and, in mid-June

1936, the Opry moved across the Cumberland River to the Dixie Tabernacle in East Nashville. Even in the larger venue, the

show was still full to overflowing every Sat-urday night.

AARON SHELTON:

The Dixie Tabernacle was a tent operation. It was a big tent set up where they had revival services during the week and on

Sunday, but on Saturday night they’d rent it out to the Grand Ole Opry.

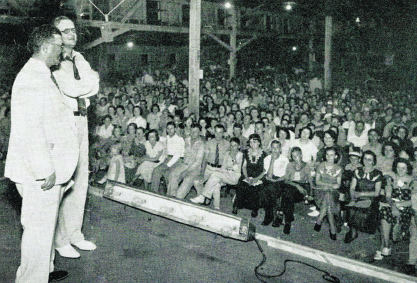

Very few photos were taken of the Opry during the years 1936–1939, when it was staged at the Dixie Tabernacle.

BASHFUL BROTHER OSWALD,

Roy Acuff’s Dobro player:

The Tabernacle had a dirt floor. Wooden benches on a concrete block, and it was free. They gave us tickets to hand out to

people on the road when we’d play a job.

DAVID STONE,

Artists Service Bureau manager:

It was like carnival days. Sawdust on the floor. Old hinged lighting along the side. You’d have to go along on a hot night

and put broomsticks under the lights to hold them up. There was no room to do anything. It held maybe six hundred or eight

hundred people.

Judge Hay is seen with Texas announcer Byron Parker, aka the Old Hired Hand.

WSM’s

Home Office Shield

magazine had a much higher estimate of the weekly attendance. The Tabernacle probably held less than one thousand people,

but some would leave during the show to be replaced by others.