The Grand Ole Opry (4 page)

Read The Grand Ole Opry Online

Authors: Colin Escott

You can’t x-ray it or do blueprints like a doctor or engineer to understand my style. It’s just in me. I can’t help it. I

don’t ask nobody to help me or show me how to do it. I just do it. You hear something all the time with my music. Other people’s

music is good, but it’s missing something. I add time to vacant space.

DeFord Bailey had two showstoppers: an imitation of a railroad train and “The Fox Chase.”

A letter to WSM’s magazine, Our Shield, dated February 7, 1928, from

MR. AND MRS. HOLLOWAY SMITH

in Jefferson City, Missouri:

Needless to say, we thoroughly enjoy your Saturday night program. I have one request to make, and that is when your harmonica

artist puts on the “Fox Hunt,” that we are given some advance notice as to what to expect. Last night my old Irish Setter

bird dog was laying in front of the fireplace when your artist reached the point in his playing where he repeated the words,

“Get him, sic him,” before anyone could interfere my old dog had turned over two floor lamps and a smoking stand.

DeFord Bailey. Hay dubbed him “the harmonica wizard.” On show dates, few of which had amplification, he played through the

megaphone seen here. To his right is a rack to create train effects.

Even with the beginning of a regular cast and steadily growing listener-ship, the future of WSM’s Barn Dance remained uncertain.

It was moved around various time slots until it became a fixture on Saturday night. Then, in 1927, it faced another threat

when WSM joined the newly launched NBC network. NBC supplied networked shows from New York and Chicago during prime time,

and the understanding was that its affiliates would fill in with locally produced shows at other times. Once again, Edwin

Craig stepped in to defend the Barn Dance.

EDWIN CRAIG:

We almost lost our NBC affiliation at one point. The network reserved the right to preempt Saturday night time on all its

stations, but we refused to go along with this. We felt that we were acting in the public interest by bringing good entertainment

to people in our own community, so we took a firm stand. We became the only station in the whole network not obligated to

give the network prime Saturday time.

Although Judge Hay was in charge of all local programming on WSM, the Barn Dance was the show closest to his heart. From its

inception, he’d been on the lookout for a new name.

JUDGE HAY:

For the first two years, our Saturday night show was called the WSM Barn Dance, which, as a name, was a “dead head,” as we

would say in the newspaper game. But with the organization of NBC, and WSM’s association with it, we carried practically full

network service. It so happened that on Saturday nights from seven to eight o’clock WSM carried the Music Appreciation Hour,

under the direction of the eminent composer and conductor Dr. Walter Damrosch. Dr. Damrosch always signed off his concert

a minute or so before eight o’clock, just before we hit the air with our mountain minstrels. The change in pace and quality

was immense, but that is part of America. The members of our radio audience who loved Dr. Damrosch and his symphony orchestra

thought we should be shot at sunrise and did not hesitate to tell us so.

The monitor in our Studio B was turned on so that we would have a rough idea of the time which was fast approaching. At about

five minutes to eight, [I] called for silence in the studio. Out of the loudspeaker came the very correct but accented voice

of Dr. Damrosch: “While most artists realize that there is no place in the classics for realism, nevertheless I am going to

break one of my own rules and present a composition by a young composer from ‘Ioway,’ who sent us his latest number, which

depicts the onrush of a locomotive....” After which, the good doctor directed his symphony orchestra through the number, which

carried many “shooses,” depicting an engine trying to come to a full stop. Then he closed his program with his usual sign-off.

Our control operator gave us the signal which indicated we were on the air. [I] said something like this, “Friends, the program

which has just come to a close was devoted to the classics. Dr. Damrosch told us that there is no place for realism in classical

music. However, for the np1 three hours we will present nothing but realism. It will be down to earth for the earthy. In respectful

contrast to Dr. Damrosch’s presentation which presents the onrush of a locomotive, we will call on one of our performers,

DeFord Bailey, to give us his version of his ‘Pan American Blues.’” At the close of it, [I] said, “For the past hour, we have

been listening to music taken largely from grand opera. From now on, we will present the Grand Ole Opry.”

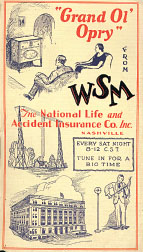

The earliest Grand Ole Opry souvenir folio, circa 1928.

No one is completely sure when the name change took place. National Life’s in-house magazine,

Our Shield,

is the best guide. On December 27, 1927, the show was still billed as “Regular barn-dance program,” but it was “The Grand

Old Op’ry” one week later. According to Judge Hay’s daughter, Margaret, he renamed it on December 10, 1927.

In later years, many artists would claim that they were there the night that WSM’s Barn Dance became the Grand Ole Opry, but

the lineup wasn’t published. In fact, the casting was so informal that Judge Hay probably didn’t have a good idea of who would

be on the show until Satur-day evening came around.

FIDDLIN’ SID HARKREADER,

early Opry performer:

I played two tunes on my fiddle the night the Opry was named. The others who were in the studio that night were Dr. Humphrey

Bate and his Possum Hunters, Burt Hutcherson, and DeFord Bailey, George Wilkerson and his Fruit Jar Drinkers, and the Binkley

Brothers. [But at that time] everyone who could play an instrument or sing old-time country music was welcome. No one at any

particular time. All they needed to do was just go by the station, and it was almost certain that they would get on the air.

Fiddlin’ Sid Harkreader.

Grand Ole Opry cast, circa 1928.

Sam and Kirk McGee from Sunny Tennessee. Sam McGee: “Just as soon as word circulated about the Opry, the Barn Dance it was

then, everybody got excited about it. Uncle Dave Macon and me were down in Alabama. He says, ‘Let’s go and play on that Barn

Dance.’ It wasn’t any trouble to get on then because it was so new and they didn’t have the people they needed.”

SAM M

C

GEE,

early Opry performer:

The Opry came down here and said they wanted players who were outstanding in the field—and that’s where they found us, out

standing in the field.

Although the Opry claims to have been on-air every Saturday night since November 28, 1925, the station itself was off the

air from some point in December 1926 until January 7, 1927, as the wattage was increased. Then, in September 1928, the Opry

was preempted by a political debate.

In its earliest years, WSM was a single-advertiser station, and that advertiser was its owner, National Life and Accident

Insurance Company. Edwin Craig’s enthusiasm for the Opry stemmed in part from his realization that the show enabled him to

write more business in rural areas. Already, it touched people in rural America in a way that no other radio program ever

had or would.

Paul Warmack (right) with the Gully Jumpers made the first record by a Nashville artist to be released. Jack DeWitt: “No one

remembers him today, but Paul Warmack was very popular. He had a big belly. I touched him on his belly, and said, ‘You’ve

done pretty well by yourself, haven’t you?’ He said, ‘It’s a mighty poor man won’t build a shed over his best tool.’ ”

National Life’s

Our Shield

ran testimonials from WSM’s listeners. Atmospheric conditions permitting, the station could be picked up across the eastern

United States.

Letter from

WILL PRENTIS,

Lincoln Avenue, Detroit, 1928:

Mrs. Prentis and I, together with our two good friends and neighbors, Mr. and Mrs. Parker, all true and loyal Southerners,

wish to p1end to you our hearty appreciation of your splendid barn-dance program, which came in perfectly last night on our

set. The music has the true ring and swing of the Old South, than which no higher compliment can be paid.