The Good and Evil Serpent (24 page)

Read The Good and Evil Serpent Online

Authors: James H. Charlesworth

Figure 33

. Clay Jar with Serpents. Middle Bronze. Courtesy of the Israel Museum.

Thus, both of these vessels seem to be Canaanite jars. They are probably luxury items made by Canaanite potters and artists. Most important, they provide significant new data for assessing the veneration of the serpent by Canaanites, ostensibly near Jericho, before the “Conquest.”

The date (1550–1200

BCE

) and alleged provenance (near Jericho) of both vessels seem especially significant. At the end of the thirteenth century, Canaanite culture was determined by four momentous events. The Hittite empire to the north collapsed, Egypt’s control of Canaan was weakened, the “Sea Peoples” began infiltrating from the West, and the Israelite tribes probably began incursions from the East.

250

Perhaps there were also local revolts and disruptions; we have previously surmised that these events may have been accompanied by, and even aided by, earthquakes.

This research has been informed by a study of the vast amount of vessels with serpents on the rim or handles in museums, antiquities dealers, and private collections. One vessel is so special for this study that I will conclude with it.

This “chocolate on white ware” ceramic serpent vessel is one of the most elegant ever found in ancient Palestine; unfortunately, its precise provenance is unknown.

251

The 32-centimeter red-clay vessel is late Canaanite (Middle Bronze Age) and dates from the middle of the second millennium

BCE

. As indicated previously, the zenith of pottery-making in ancient Canaanite culture corresponded with the time of this object.

The serpent was certainly a popular “decoration” on Canaanite vessels. They are rarely so ornately depicted as in the present example; here they are realistic and obviously snakes. They appear to curl upward as if moving. The bodies are punctuated by tiny holes to signify skin (as in most examples). The eyes are detailed, and again it is wise to recall that usually the eyes receive the attention of the ancient artist or worker. On other vessels the snakes are merely appliqued round pieces of clay without any indications of a mouth, eyes, or scales. It would be counterintuitive to imagine that such snakes are only decorations.

What did the two serpents symbolize to the maker of this vessel and to those who used it? The placing of the serpents is crucial. One could imagine that the owner wanted the serpents to obtain a drink of water or milk. That makes sense in a serpent cult civilization as in ancient Canaan. But they could be placed there to protect and guard the contents, probably wine, milk, or water. Clearly, the serpents add to the beauty of the vessel, so beauty and aesthetics also come into play as we ponder serpent iconography.

ARCHAEOLOGICAL EVIDENCE OF THE INFLUENCE OF GRECO-ROMAN OPHIDIAN ICONOGRAPHY IN ANCIENT PALESTINE: THE JEWELRY OF POMPEII AND JERUSALEM

Anguine jewelry has been found in the ruins of Pompeii. As is well known, this city south of Rome was destroyed in 79

CE

when the volcano Vesuvius erupted. Here are the words of Pliny the Younger, who witnessed the horrifying event:

Ashes were already falling, not as yet very thickly. I looked round: a dense black cloud was coming up behind us, spreading over the earth like a flood. … We had scarcely sat down to rest when darkness fell, not the dark of a moonless or cloudy night, but as if the lamp had been put out in a closed room. You could hear the shrieks of women, the wailing of infants, the shouting of men; some were calling their parents, others their children or their wives, trying to recognize them by their voices. … Many besought the aid of the gods, but still more imagined there were no gods left, and that the universe was plunged into eternal darkness for evermore.

252

Pliny was with his mother on a high hill north of Pompeii and Vesuvius; he was visiting his uncle, Pliny the Elder. The latter’s inquisitive nature not only provides us with valuable information about ancient society, including the Essenes who lived at Qumran; it also led to his death on the shores west of Pompeii as he was seeking to explore the events of 79

CE

.

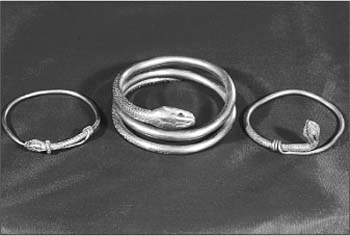

Figure 34

. Pompeii. Serpent jewelry. Naples Antiquities Museum. I thank the Soprintendenza Archeologica delle Provincie di Napoli e Caserta and Professor Marcello del Verme for assistance and permission to publish this photograph. JHC

At least four beautiful anguine bracelets have been recovered from the debris in Pompeii. The elegant gold bracelets shown in

Figs. 34

and

35

perhaps were crafted within the one hundred years that preceded 79

CE

.

253

Note the detail of the serpents. The eyes are clearly marked, sometimes with a jewel. The head and skin are detailed. These are not stylized serpents; these are snakes. The gold jewelry bracelets from Pompeii and the gold ring from Alexandria (perhaps) are impressive and draw one’s attention and admiration. They were crafted and intended to be displayed prominently.

There is ample evidence that wealthy women wanted to be seen with anguine jewelry. Surely, something positive was symbolized by these works of art. It is clear that serpents were admired, even worshipped, at Pompeii. More can be surmised about the symbol of the serpent among the residents at Pompeii.

At Pompeii the Romans apparently worshipped various gods through Agathadaimon (the good serpent or demon). This god of goodness is often represented on gems with the sacred cista (the box in which mysteries were kept) and as a serpent or a human-bird figure with serpents as feet (anguipedes). Agathadaimon was revered in Pompeii and openly. This is certain because a painting of this serpent can still be seen in the House of the Vettii. In this room, the occupants of the house gathered in a sacred place to devote themselves to the household gods (the Lares).

Figure 35

. Pompeii. Gold Jewelry; reference no. 1946,7–2,2 (transparency number PS208051). British Museum Ring no. 950. Courtesy of the Trustees of the British Museum.

Gold anguine symbols do not appear only on jewelry. They appear also as serpents. At Herculaneum, in the Palaestra, a massive bronze serpent with five heads spewed water into the swimming pool.

254

This serpent image is unrealistic, but replicas of snakes are often strikingly lifelike and realistic. One example was the pride and joy of Leo Mildenberg. He published many of his serpent realia, including the cornelian snake head attachment (third-second cent.

BCE

), bronze snake with eight undulations (c. 1320–1200

BCE

), gray granite cobra goddess (Greco-Roman), and bronze snake with five undulations (first-second cent.

CE

).

255

As far as I know, he never published his gold snake, which, as he reported to me, was found in southern Italy and dates from the Roman Period.

256

Evidence of the popularity of anguine jewelry is present not only in the West, in Pompeii, but also in the East, including Jerusalem.

257

For the Roman Period, there is a vast amount of evidence. I have seen gold, silver, and bronze serpent armbands, earrings, and especially bracelets. Because of their composition and the quality of their artwork some of the jewelry belonged to the upper classes and others to the poorer people.

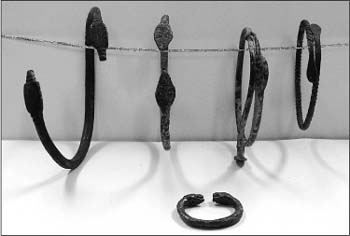

Figure 38

displays four bronze bracelets and one bronze ring. All are from the early Roman Period and were found in or near Jerusalem.

258

Like so many other illustrations, they appear here for the first time. From left to right: the first and last bracelets show a stylized serpent, the next has the two eyes of the serpent etched in an enlarged manner. Because of the quality of the bronze work, it is likely that these bracelets belonged to rather wealthy persons. The next to last one is crude; the head of the snake, with the elongated tongue, is merely wrapped around the bronze; this bracelet probably belonged to one who was not wealthy. The ring below the bracelets is artistically crafted; the mouths of the serpents are open and the eyes and heads are professionally designed. More detail was poured into it than the serpent ring found at Herculaneum.

259

Figure 36

. Pompeii. Agathadaimon. JHC

Figure 37

. Leo Mildenberg and Author with Gold Snake Jewelry.

Figure 38

. Four Bronze Bracelets and One Silver Ring. Early Roman Period. All from Jerusalem or nearby. JHC Collection