The Good and Evil Serpent (18 page)

Read The Good and Evil Serpent Online

Authors: James H. Charlesworth

It is clear that the ophidian iconography found at Hazor has deep symbolic meanings. For example, the pendant serpent, like the later so-called gnostic amulets, might serve to symbolize the one who can protect the bearer from misfortune, especially through sympathetic magic, from a deadly snakebite. Like most amulets, it was most likely prophylactic and apotropaic—that is, used to ward off evil.

Timna’ (Tel Matash)

Timna’ is a valley about 30 kilometers north of the Gulf of Aqabah. Copper smelting installations were active at Timna’ from the Chalcolithic Period to the Byzantine Period.

A Midianite votive offering was found in the Hathor Temple at Timna’.

93

It is a serpent from the thirteenth century

BCE

.

94

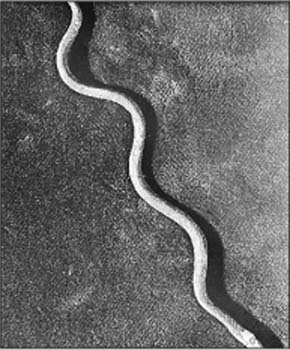

The serpent is primarily copper, but its head is gilded and the eyes highlighted. The gold that remains around the face and the way it ends behind the eyes suggest that the whole serpent originally was covered with gold. Its skin is artistically represented. The head is pointed and its eyes clearly marked with recessed circles in the gilded copper. It has seven well-defined undulations, and the tail curves. It is less than 13 centimeters long. Since it was found in the Egyptian Temple to Hathor, it probably symbolized divinity and protection. Also, since Hathor is the goddess of mining, it most likely also signified success and prosperity in mining.

95

Also found at Timna

c

was another ophidian object. It is a snake crawling along the rim of a votive altar.

96

It should be evident that these examples of snake iconography denoted something positive; the gilded serpent was found in a temple and should be interpreted in terms of the goddess of the temple, Hathor. In Canaanite religion this goddess was associated with vegetation;

97

in Egypt she was a cow and the serpent who ruled the world. The Timna

c

gilded serpent probably denotes Hathor’s divinity. As is well known, the serpent was a god and the assistant of gods in ancient Egypt. One papyrus of about 990

BCE

depicted four cobra gods and a gigantic serpent guiding the boat of the sun god.

98

Figure 22

. Timna’. Gilded Serpent. 1550–1200 BCE. Courtesy of the Israel Museum.

Beth Shan (Beth-shan, Beth Shean, Beisan)

The site in which the most abundant and impressive ophidian iconography has been discovered in Palestine is Beth Shan, a prominent tell (Tel el-Hosn) in the valley of the Harod, a stream that flows into the Jordan River.

99

The site was apparently deserted from 700

BCE

until the time of Alexander the Great; then it was renamed Scythopolis. On the tell, archaeologists have found abundant evidence of Egyptian influence, which is understandable since an Egyptian garrison was stationed there in the period from Seti I to Rameses III, or from circa 1318 to circa 1166/67

BCE

.

Quite confusing are the dates given to the numerous strata of the tell, and these are often debated.

100

I have thus decided to treat them together, with asides about the dates assigned to them by Alan Rowe, the field director of the excavations in the 1920s and the author of the two volumes that reported and assessed the discoveries. Serpent iconography is dated long after the period of Hyksos control, or beginning in MBIIB and C; this information may strengthen the thesis that the Hyksos brought ophidian symbolism into Palestine if one adds to it the increase of such symbolism under Egyptian domination.

Here is an inventory of ophidian iconography excavated at Beth Shan.

101

1. A fragmented cylindrical cult stand with four serpents (14:1 [1021A]). There appear to be four apertures: one rectangular-like aperture on opposite sides.

102

The top is crowned. Large serpents with dots indicating the skin are depicted moving upward and into the apertures (photo on 58A:1–2, drawing on 58A:3).

103

Doves clearly sit above each handle. Rowe assigned this stand to the time of Rameses III (1183–1152

BCE

). It was found in the southern temple.

2. A fragment of a second cylindrical cult object with a serpent and the top of an oval aperture (16:4 [1021]). Rowe dated it to the southern temple of Rameses III.

3. A third fragmented cylindrical cult stand showing serpents with dots and along with doves (14: 3, 4, 5 [1027, 1029]).

104

Around the cylinder, with a sloping top, portions of doves are depicted in eight (perhaps)

105

triangular-shaped apertures. Originally a dove was in each hole. Four serpents curled around the doves, but did not enter the openings (photo on 57A:3; drawing on 57A:4).

106

Doves most likely also originally sat on each handle.

What did this serpent iconography symbolize? The scene is peaceful and the serpents are not heading for the doves. It seems unlikely that the ancients imagined the serpents were seeking the doves for food. Perhaps the doves and the serpents represented the beginning of spring, with the doves symbolizing heaven and the serpents the earth and beneath it. Rowe dated the serpent cult stand to Rameses III. It was found in the southern temple.

4. A fourth fragmented cylindrical cult stand with serpents and doves. It has two triangular openings (base below) with a dove in each and two serpents with heads facing the doves (16:3 [1080]). Rowe dated it to Rameses III. Like items one, two, and three, it was also found in the southern temple.

5. A fifth very fragmented cylindrical cult stand, with doves and serpents (16:1 [1024]).

107

Each of the two oval apertures probably originally held a dove. A serpent faced each dove. The cult stand was found under the plaster floor of the northern temple from the time of Rameses III.

6. A fragmented base of a sixth cylindrical cult stand with serpents at the bottom, not to be confused with the previous five items. The cult stand shows serpents with tiny dots and semirectangular windows or apertures. Thus, the archaeologists found at least six cylindrical serpent cult stands at Beth Shan.

Rowe reported that seven cylindrical cult stands with serpents were found at Beth Shan.

108

Only the six previously reported are clear in the plates.

109

None of these cylindrical cult stands is as ornate as the one found at Byblos that has bulls below the rim and serpents near square windows.

110

7. A cult object; a serpent curled up in a U-shape (19:1). Rowe reported that this artifact is the only cult object that was found in the “Pre-Amenophis III Level.”

111

By analogy with passages in the Pyramid Texts and ophidian symbolism found in Egypt, it is likely that this object was set up at the entrance to a temple as a guardian.

112

8. Another serpent with dots; it is lying in a serpentine line (19:8).

9. A pottery serpent in a serpentine line (20:2).

10. A pottery cult object; serpent coiled back on itself, head broken off. Rowe dated it to Amenophis III or 1386–1349

BCE

(20:3; see the photo on 44A:5).

113

11. A pottery cult object; an undulating serpent on a base with head missing, dated by Rowe to Seti I or 1313–1292

BCE

(21:15; see the photo on 42A:5).

12. Small pieces of ivory that are perhaps the remains of serpents (30:21–31).

13. Tiny bronze pieces that are probably the remains of serpents (31:25 especially).

14. A faience Egyptian-like pendant that is an upraised serpent or uraeus with a human face like a sphinx (33:7).

114

15., 16., 17. Three faience pendants that look like Egyptian cobras (34:42, 61, 62).

115

18. A serpent cult object with head broken off, which Rowe dated before Amenophis III or prior to 1447

BCE

(41A:2, 21:5).

19. A pottery cult object, an upraised serpent, like a cobra,

116

with female breasts indicated by two circular deposits of clay. The head is lost. Rowe dated it also before 1447 (42A:2).

117

20., 21. Two clay cult objects, serpents most likely. One is with a cup; perhaps the cup was intended to catch lacteal fluid from the two breasts, as Rowe thought, both with a vertical slip of clay (to denote cleavage?; 42A:5).

118

Each seems to be an upraised serpent, perhaps a cobra like the uraeus, and each appears related to the cult at Beth Shan that reveals strong Egyptian influence. These ophidian symbols, and the preceding one, probably denoted a goddess or symbolized one of her attributes.

22. A pottery cult object; a serpent—probably a cobra—depicted with female breasts and a receptacle beneath them, most likely to capture lacteal fluid. Rowe dated it to the time of Amenophis III or 1447–1412

BCE

(45A:4; cf. 42A:5).

119

Found with Ashtoreth figurine, whose hands cup naked female breasts (45A:5). This cult serpent also represented a goddess or her attributes.

23. Numerous fragments of a rectangularly shaped cult shrine house with a serpent on the front moving up to rest beneath a man’s feet and near the feet of a dove. Above the gracefully curved serpent are two men, reaching over to touch the head of the other.

120

A nude woman sits above them with her legs separated to show her exaggerated mons veneris. On the right is a walking lion. Most of the appliqued clay for the serpent has broken off. Rowe dated this shrine to Rameses (56A:1–3, 17:1–3, 57A:1–2; cf. 17:2, 17A:1–2). It is on display in the Israel Museum. This rectangular serpent cult stand is not be confused with the six cylindrical ones.

24–27+. In 1973, E. D. Oren published for the first time the report on the 1920 to 1931 excavations of the northern cemetery of Beth Shan. In this northern cemetery were found the following ophidian objects: (a) in Tomb 7, from EBIV, four uraei carnelian pendants,

121

(b) in Tomb 27, contents from the Late Bronze Age, a white steatite scarab with two uraei whose bodies contain a crisscross design, facing in opposite directions, with a cartouche with

Aa-kheperw-Ra

, the prenomen of Amenophis II,

122

(c) and in Tomb 219, EBIV, one faience scarab with a single uraeus facing a reed sign.

123

These are not to be confused with numbers 14–17 that are faience pendants with ophidian imagery.

One notable feature seems impressive. Most of the serpent objects have their heads broken off. Is this intentional? The broken heads do seem to distinguish the serpent objects from others found at Beth Shan. Note the following examples: cracked pottery with a serpent whose head is partly missing (20:2), serpent base with head missing (20:3 = 44A:4), a pottery cult object showing a serpent head missing (21:15), a serpent cult object with head missing (41A:2), serpent cult object with female breasts and head broken off (42A:2), two serpents, cult objects, with heads missing (42A:5), serpent cult object with breasts and a cup for lacteal fluid (45A:4). Infrequently, other objects also appear as if someone has broken them or smashed the head; note especially the Ashtoreth (45A:5). Also, recall that the six cylindrical and one rectangular cult stands with serpents are fragmented. Are these broken serpent objects related to Hezekiah’s reform? He did banish the worshippers of Nechushtan (the serpent idol) from the Jerusalem Temple.

It seems relatively certain that Beth Shan, beginning in the second millennium

BCE

, was the center of a serpent cult.

124

The worship of the serpent there may have given rise to the name; for example, N. H. Snaith was convinced that “Beth-shan means ‘house of the snake.’ “

125

In fact, so many serpent objects were found at Beth Shan that the categories are often shaped by serpent iconography. For example, the so-called Beth Shan sacred boxes are divided into those with serpents, those with serpents and doves, and those without serpents and doves.

126

There can be no doubt that before Beth Shan fell to the Israelites it was the center of a cult in which serpents and doves represented a fertility goddess. Serpent iconography thus most likely symbolized power, health, rejuvenation, and life.

127

There can also be no doubt that the deity worshipped at Beth Shan was symbolized as a serpent, and since the ophidian iconography often has breasts, we should conclude that a serpent goddess was worshipped there. The association of the serpent and the dove indicates that both may well have been related to the celebration of spring and the return of vegetation. To what extent is Jesus’ statement about serpents and doves informed, and once understood, in terms of the ancient association of serpents and doves: “Be wise as serpents and innocent as doves” (Mt 10:16; NRSV)?