When the Devil's Idle

Idle

A

Greek Islands Mystery

* * *

Coffeetown Press

PO Box 70515

Seattle, WA 98127

For more information go to:

www.coffeetownpress.com

www.letaserafim.com

All rights reserved. No part of this book may

be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means,

electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any

information storage and retrieval system, without permission in

writing from the publisher.

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters,

places, brands, media, and incidents are either the product of the

author’s imagination or are used fictitiously.

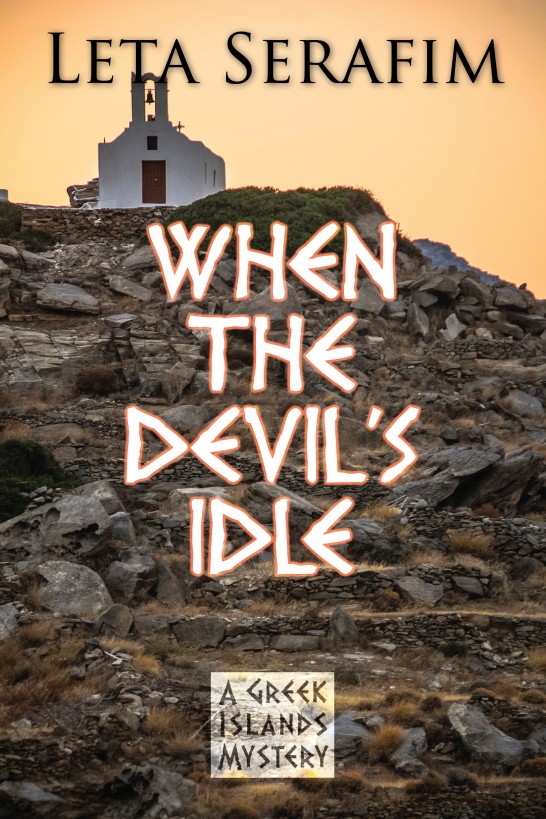

Cover design by Sabrina Sun

When the Devil’s Idle

Copyright © 2015 by Leta Serafim

ISBN: 978-1-60381-998-5 (Trade

Paper)

ISBN: 978-1-60381-999-2 (eBook)

Library of Congress Control Number:

2015938969

Produced in the United States of

America

* * *

For

Philip

* * *

T

he following people were instrumental in the writing

of this book. First and foremost, my husband, Philip Evangelos

Serafim. Also my friends Dawn Lefakis, Stephanie Merakos, and

Thalia Papageorgiou, my daughters and their husbands: Amalia

Serafim and David Hartnagel, Annie and Yiannis Baltopoulos. I would

also like to thank my precious grandchildren, Zoe and Grace

Hartnagel and George Baltopoulos.

My thanks to all

the people who have encouraged me to continue with the Greek Island

Mystery series: my agent, Jeanie Loiacano, Jennifer McCord and

Catherine Treadgold at Coffeetown Press, and my late parents, John

and Ethel Naugle.

* * *

An old enemy cannot become a friend.

—Greek Proverb

N

ight was fast approaching and the garden was

half-hidden in shadows. The gardener unlocked the gate and quickly

set about his evening’s work, watering the roses first before

moving on to the cypress trees at the periphery of the estate. The

air was very still; the only sound, a flock of birds chattering by

the fountain. The estate, cloistered on a hilltop and located in

the village of Chora on the Greek island of Patmos, was well off

the tourist trail. People rarely ventured there uninvited.

The gardener

lingered by the fountain, enjoying the sound of the cascading water

and the coolness it brought to the hot, late-summer air. He dipped

his hand in the water and wiped his face.

Distracted, he

didn’t notice the wounded man at first, lying in a congealing pool

of blood on the far side of the fountain. It was the birds that

drew him. Crows, from the sound of them, far too many for this time

of night.

His eyes open,

the man lay sprawled on the ground, barely breathing. His hair was

matted with blood and his forehead was carved with a

swastika.

The gardener fell

to his knees and screamed and screamed. He was far from the house,

so no one heard his cries. Growing more and more desperate, he ran

to the door and began pounding on it, crying for help. Eventually a

woman answered. Pushing his way into the house, he demanded her

cellphone and called the police. The station was located in the

port of Skala, four kilometers away, the village of Chora being far

too small to warrant its own station.

There was much

shouting back and forth, given the poor connection, before the

gardener finally yelled, “

Dolofonia

!” Murder.

At first the

police dispatcher was skeptical and doubted the man’s story, but

the hysteria in the Albanian’s voice finally convinced him to send

someone, if only to lock him up in a padded cell.

A policeman named

Evangelos Demos duly arrived on the scene.

* * *

It was, as he

later told his former supervisor, Yiannis Patronas, exactly as the

gardener described.

“

Bloody?”

“

Yes.

One of the worst crime scenes I’ve ever seen.” This was hardly

significant. Evangelos Demos was no expert, having seen only one

other crime scene in his life, a bloody mess on a beach. On that

occasion he had fainted dead away, going down like a sequoia tree

and vomiting as he went, contaminating every scrap of evidence. He

was notorious among law enforcement officials in Greece, a legend

almost.

“

There

was an old woman who pulled me aside as I was leaving the house.

‘

Prosehe

,’ she said.” Be careful.

Patronas had been

at a taverna on the Greek island of Chios when the call came in,

eating dinner with an elderly priest named Papa Michalis. The two

were old friends and it was an idyllic evening. Far to the east,

the moon was rising and he could see the dusky hills of Turkey

across the narrow channel that divided the two countries, along

with headlights of cars in the streets of Chesme.

Between them, the

two had drunk nearly a liter of ouzo and were discussing the nature

of evil, whether it was generated by humans or an independent

entity. The priest, being a religious man, favored the latter view,

quoting the Bible to bolster his case. “ ‘I saw Satan fall

like lightning from heaven,’ it says in the New Testament. ‘For God

spared not the angels that sinned, but cast them down to hell and

delivered them into chains.’ ”

Patronas snorted.

“So our troubles are caused by fallen angels?” As the Chief Officer

of the Chios police, he’d seen plenty of the fallen and arrested

more than a few of them, but he’d never encountered an angel. Not a

single one in all his years on the force or in his tumultuous

married life. Just the opposite in fact.

But the priest

was not to be put off. “Fallen angels, the devil, call it what you

will. There’s too much evil in the world to be the work of man

alone.”

Patronas was

later to recall that conversation. Papa Michalis had spoken the

truth that night. Evil was indeed an entity and certain human

beings embodied it, wore it like skin. He just hadn’t realized it

at the time.

When his phone

rang, he hesitated, not wanting the evening to end.

“

Chief

Officer Patronas?” a man asked.

Patronas cursed,

recognizing the tremulous whine of his former associate, Evangelos

Demos. Fat and incompetent, he’d been forced out of the Chios

Police Directorate after panicking during a stakeout and shooting

up a herd of goats. It had been one of the worst nights of

Patronas’ career, Evangelos firing away with his service revolver

and the goats falling, writhing, and shitting themselves as they

bled to death. “Get rid of him,” Patronas had told his superior at

the time. “No living creature is safe while Evangelos Demos is on

the job. He does harm just by breathing.”

As usually

happened, his superior in Athens, a self-serving bureaucrat named

Haralambos Stathis, had ignored his warning and reassigned

Evangelos Demos to Patmos. His duties there were few: overseeing

the cruise ships that docked there and the hundreds of foreign

tourists on holiday who inevitably drank too much and got into

trouble.

“

It’s

as far away as we can send him and still be on dry land,” Stathis

had told Patronas at the time. “Any farther east and he’ll be

policing fishes.”

Pity the

fishes.

“

Why

don’t you just fire him?”

“

His

uncle is a representative from Sparta.” This being Greece, it was a

sufficient reason.

Ever the parade

horse, his old colleague Evangelos Demos had become insufferable

since being posted to Patmos, bragging about the celebrities he

knew—Aga Khan and the like—who summered there. Although he’d been

totally disgraced and his uncle had been forced to call in favors

to save his career, Evangelos always spoke as if he expected to be

listened to, prefacing every remark with ‘

na sou po

’—let me

tell you—and pontificating as if he were king. This time was no

exception.

Irritated,

Patronas reached for his cigarettes. Just thinking about Evangelos

made his blood boil. He wanted to hang up, but didn’t dare. He was

already considered a troublemaker, an outlaw, a rogue. No reason to

make matters worse.

“

There’s a dead German here,” Evangelos’ voice dropped

dramatically, “murdered.”

Patronas puffed

furiously on his cigarette. He needed to get a new phone, one with

a screen that showed who was calling.

Homicide was rare

in Greece, the murder of a foreigner, rarer still. After solving a

case on Chios, he had become a celebrity of sorts among policemen

and was often consulted by colleagues like Evangelos on difficult

cases. Patronas didn’t welcome the attention and wished they’d

leave him alone. It had hardly been an achievement, that case on

Chios, botched as it was from start to finish. Yes, he’d caught the

killer, but it had been more by accident than design and only after

the perpetrator had murdered three people and sliced him to

ribbons. A rank amateur, he recognized his limitations. He only

wished others did.

“

I

don’t know where to start,” Evangelos went on in an

uncharacteristic burst of modesty.

“

You

said the victim was German?”

“

That’s right. Someone carved a swastika on his

forehead.”

“

One

of those skinheads? A tourist?”

Evangelos knew

what Patronas was asking. Sometimes foreigners got into things,

strange things better left alone. “No, the victim was an old

man.”

“

How

old?”

“

Eight-nine, ninety. Old, old.”

Patronas gave a

low whistle. “Was it a robbery?”

“

I

don’t think so. He was staying in Chora with his family, guests of

an industrialist in Munich. A very powerful man. There’s a bunch of

them here now. Unlike us, they’ve got money to burn and bought up a

bunch of old villas. Spend July and August

there ….”

The priest, who’d

been listening, chuckled softly. “Summer, autumn, war.” It was an

old saying, dating from the time of the Spartans, on the

inevitability of war, the enduring presence of one’s

enemies.

“

Germans haven’t made it to Chios,” said Patronas.

“

You’re lucky,” Evangelos said. “They’re all over Patmos now.

Couldn’t get here with Hitler, so they bought their way in this

time. Their weapon of choice, the Euro.” His voice was

bitter.

Patronas had

heard similar complaints—Germans making themselves at home in

places where they didn’t belong. Ieropetra in Crete, for example, a

village which suffered one of the bloodiest massacres of the war.

The newcomers had no compunction about it, apparently, no sense

that it was hallowed ground and they shouldn’t trespass. Idly, he

wondered what the Israelis would do if Germans turned up en masse

in Tel Aviv, beach towels in hand, eager to buy property. Be

interesting to see.

Hospitality was a

Greek virtue and had been since ancient times. Guests were to be

honored, given the best food, the last drop of wine. But what if

they never left, those guests? Stayed on and bought houses and

lived there beside you? What was the difference between a guest and

the advance guard of an invading army? Patronas didn’t know the

answer. Wasn’t sure there was one.

“

You

have to help me,” Evangelos said. “I can’t do this alone.” There

was something in his voice as he said this. Fear maybe.

“

What

about my job?” Patronas asked.

“

I

cleared it with Athens.”

“

I

don’t know if you know this, Evangelos, but I got a second job

since you left Chios, overseeing the security on an archeological

dig.”

In addition to

his police work, Patronas and a friend of his from the force,

Giorgos Tembelos, worked part-time as guards on an excavation run

by Harvard University. The job was easy and the pay was good. He’d

be a fool to abandon it. Times were tough now in Greece. In spite

of his twenty-two years on the force, he could be laid off at any

time.