The Goats (4 page)

Authors: Brock Cole

“Okay.”

He watched her get up and start toward the concession stand. She was almost marching. He thought he should have picked somewhere else to meet in case they had to run, but it was too late now. He stood up and wiped his hands on his pants. They were wet and sticky.

There was a little boy ahead of her buying a popsicle, so she had to wait. The man frowned over the little boy's head. He looked first at her and then at the piece of hot dog in her hand.

She couldn't see what was going on at the other counter because the man was in the way, and she was afraid to try and look around him. She realized suddenly that she should have waited until the man had taken the wire baskets from the blond couple. The boy wouldn't be able to grab anything if they were standing there. It was too late. The little boy in front of her moved away, pulling the sticky wrapper from his popsicle. The man didn't ask what the girl wanted. He just looked at her.

“There was a rock in my hot dog,” she said. Her voice came out tight and squeaky.

“Sure. Beat it.” The man picked up a dirty wet cloth and started wiping the counter.

“There was.”

“Sure there was. And you want your money back.”

“No.”

The man looked up, faintly surprised.

“I want another hot dog. This one wasn't any good.”

The blond couple came out from behind the concession stand. The boyfriend was trying to fasten a safety pin with a brass tag to the strap of the girl's swimsuit. She was watching him look into her top and smiling.

“What is it with you guys that the bug is always in the last bite?” said the man, starting to turn away. He was bored. His look suggested that he had heard it all before.

“It was! And it wasn't a bug. It was a rock!” She heard herself shouting, trying to hold his attention. “You give me another hot dog or I'll call the cops.”

“Sure. You do that ⦔ The man was looking at the blond couple, a puzzled look taking shape on his face. He was going to wonder in one second where they had got their brass tags.

“I want one!” she shouted, slapping the counter with her bare hand as hard as she could. It made a terrific noise, and her arm tingled. She and the man looked at each other, shocked.

“For Pete's sake, give her another hot dog,” said someone behind her. It was the man who had been putting up the volleyball net. His kids were swinging on his hands, looking at her.

“That girl has on a funny swimsuit,” announced the little girl, who was short enough to see.

The counterman didn't pay any attention. He was leaning past her, talking to the man. “Listen, bud. If you knew the grief these kids give me ⦔

The girl walked stiffly away. She knew she should

stay. She knew she hadn't given him enough time. She knew it.

stay. She knew she hadn't given him enough time. She knew it.

He was standing hunched over two baskets behind the changing stalls.

“What took you so long?” he asked, shoving a basket with a pink sweater on top into her hands.

“How did you get them? Weren't those people there?”

“Yeah. I just went behind the counter and gave them some tags. They must have thought I worked there. That's her stuff.” He pointed at the basket. “Hurry up and get changed.” He scuttled away, darting into an empty stall.

He dressed quickly and then waited with his door open a crack until he saw her come out of a stall down the row. She was wearing high tops, baggy designer jeans, and a pink sweater over a T-shirt that said

Milk

Bar

. She stood very straight, and when she turned toward him, she smiled nervously.

Milk

Bar

. She stood very straight, and when she turned toward him, she smiled nervously.

They walked without speaking across the parking lot. His legs weren't working too well. He wanted to break into a run, a screaming gallop into the trees. It wasn't because he was afraid. He was almost rigid with pent-up excitement. It felt like joy.

She stopped and scooped up the bag of potato chips she had left by the railroad ties, and they walked together down the drive toward the highway, eating the chips one by one.

When they were out of sight of the concession stand, he went through his pockets. He found a quarter

and a small brown spiral notebook with the stub of a pencil stuck in the binding. Inside were some addresses. He tore these out because they made him feel uncomfortable, but he put the notebook back in his pocket.

and a small brown spiral notebook with the stub of a pencil stuck in the binding. Inside were some addresses. He tore these out because they made him feel uncomfortable, but he put the notebook back in his pocket.

“Did you find anything?” he asked.

She frowned. “There was her wallet and watch, but I left them in the basket.”

“That's okay,” he said quickly. “We don't need them or anything. We shouldn't take stuff we don't need.”

“Wait a sec,” she said, and pulled something from under her sweater and shoved it into the bushes. It was the underwear that she had made out of the old T-shirt at the cottage.

“I didn't want anybody to find them,” she explained.

“Did you put on her underwear?” he asked.

“Sure, didn't you?”

“No.” He had shoved the boyfriend's jockey shorts under the seat in the changing stall. They had been warm, and he hadn't even wanted to touch them. “I just didn't want to.”

“Hers were clean and everything.” She walked beside him, smiling to herself. She wouldn't look at him.

“What are you smiling about?” he asked.

She looked around. The road was empty. The sun was shining through the leaves overhead and lying in flat puzzle pieces in the dust. She unfastened her

jeans and pushed them down a little. She was wearing tiny bikini panties. They were pink and mostly lace.

jeans and pushed them down a little. She was wearing tiny bikini panties. They were pink and mostly lace.

“Hey, you dope! Pull your pants up!” he said, flapping his hands.

She didn't mind. She fastened her jeans calmly, still smiling. As they walked, they bumped shoulders. He thought he would like to hold her hand, but he couldn't because she would think he liked her in that way. So he bumped her shoulder again.

“Hey,” she said, bumping him back. They began to run down the road, careening off one another through the patches of shadow and sun.

“HOW MUCH have we got?”

The girl counted the change again, although they both knew. “Forty-one cents. That must be enough for something.”

“I don't know. We can probably buy Life Savers or something.”

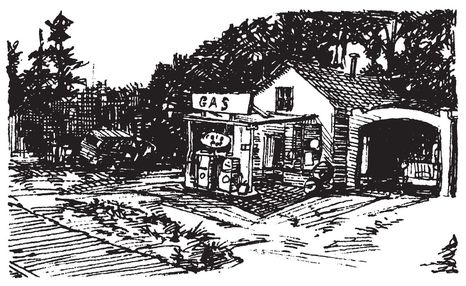

They both looked across the road at the gas station. It was old, with wooden siding that had settled into wavy lines. Someone had hung a large metal sign over the pumps. It said COLD POP.

Two bright-yellow school buses were parked on the highway shoulder. Kids were lined up at the restrooms stuck out in the pines to one side of the station. A few were dancing around the pumps, the headphones

of transistor radios clamped over their ears. Most of the kids were black. A white man in Bermuda shorts with a clipboard was leaning through the open door of one of the buses, talking to someone they couldn't see.

of transistor radios clamped over their ears. Most of the kids were black. A white man in Bermuda shorts with a clipboard was leaning through the open door of one of the buses, talking to someone they couldn't see.

“Shall we wait until they go?”

“No. I don't know why we should. Maybe it's better this way. No one will notice us in the crowd.”

The inside of the station was crowded with more kids. Some of them were feeding quarters and dimes into a candy machine. They were watching bags of chips and cookies spiraling out on metal coils behind the glass front. A man in greasy overalls and a cap that said

Corn King

was watching them unhappily.

Corn King

was watching them unhappily.

“You! Cut that out,” he said to a tall black teenager who was slapping the machine with his hand.

“This mother just ate my quarter.”

“I'll give you another. Just don't hit the machine.”

The boy tried to work his way through the crowd. People bumped him, not seeing him. He felt invisible. He couldn't find the beginning of the line where he could wait his turn to use the machine. There didn't seem to be one. Someone gave him a nudge, and he was about to nudge back when the girl caught his hand and pulled him toward the door.

“Hey. What's wrong? I didn't get anything yet.”

She jerked her head toward the window. Through the dusty glass he could see that a police car had pulled into the station. Behind it was the gray Toyota Land Cruiser that belonged to the camp. As he and

the girl watched, Margo Cutter got out of the Toyota and went up to the police car. She leaned over so she could talk to the policeman inside.

the girl watched, Margo Cutter got out of the Toyota and went up to the police car. She leaned over so she could talk to the policeman inside.

“Come on. We have to get out of here,” said the boy.

“Where?”

“We'll get into the woods out back. Let's go before everybody leaves.”

They slipped through the door, trying to keep the other kids between them and Margo. It wasn't too hard. Most of the kids were bigger than they were. The man with the clipboard blew his whistle, and slowly the crowd began to meander toward the buses.

Margo had turned around and was looking in their direction. She was squinting into the sun, and put her hand up to shade her eyes.

They kept their heads down, hoping they wouldn't be noticed. The boy took the girl's hand and tried to sidle into the shelter of the trees. The man with the clipboard grabbed his shoulder.

“Come on. Get on the bus and quit horsing around.”

The boy ducked his head and pushed the girl up the steps into the bus.

“Sit here,” he said, pulling her into the seat behind the driver. He wanted to be near the door in case they had to make a break for it.

Margo had left the police car and begun to walk toward the bus. He had a terrible feeling that they

were trapped. He craned his head around, but the back of the bus seemed crammed with suitcases and luggage. They weren't supposed to do that. They weren't supposed to block the emergency exit.

were trapped. He craned his head around, but the back of the bus seemed crammed with suitcases and luggage. They weren't supposed to do that. They weren't supposed to block the emergency exit.

“Hey! What you doing in our seats?” A tall, heavy, black girl was frowning down on them. A fringe of blue-and-pink beads woven into her hair hung down over her eyes. She looked fierce and very angry.

Before the boy could answer, the teenager who had lost his quarter in the machine took the black girl's elbow and steered her into the seat behind them. “Sit down, Tiwanda,” he said.

“What you doing? That's Tyrone's seat. I want my seat.” They sat down, whispering furiously.

The bus seemed full now. A white man with a gray face was moving down the aisle, counting with his hands, not letting anyone catch his eye. Through the windshield the boy could see Margo. She was standing in the middle of the drive talking to the garage-man. The policeman had gotten out of his police car and was walking toward them. He was wearing black aviator glasses. As he walked he lifted his gray straw trooper's hat and smoothed back his hair.

“Forty-two,” said the bus driver out loud, coming back to the front of the bus. He put his hands on his hips and frowned down the aisle.

The man with the clipboard climbed the steps up into the bus so that he filled the doorway. “What's holding things up, Wayne?”

“Nothing, I guess. I've got two too many.”

“Crap. Are any of you supposed to be on the other bus?” the man with the clipboard yelled.

“That's me, man,” said someone behind them. “I'm supposed to be on the other bus.”

“No, he ain't, Mr. Carlson. That's me. I'm supposed to be on the other bus with Lydia.”

“What you talking about Lydia?” someone demanded. The boy could feel the bus shake as people started standing up.

“Everybody sit down!” said the man with the clipboard. “We've got them all, Wayne. Let's get going.”

The bus driver waited until the man called Carlson backed down the steps, and then he cranked the door closed and started the bus. As they pulled past the gas station, the boy could see the top of Margo's head. She was shaking it. In anger, frustration; he couldn't tell.

The bus picked up speed. Dark pine forests stretched off invitingly on either side. A few feet from the road they were so dark that he couldn't see into them. The girl picked at his shirt.

“Where are we going?” she mouthed at him silently.

He shrugged and tried to smile at her. She made a face of mock terror and rolled against him.

Someone was pulling at the back of their seat, and he looked up. A thin smiling black face was leaning over them.

“Hey. How's my man?”

“Okay.”

The black teenager smiled and nodded as if that were the right answer.

“That your chick?” he asked, tipping his head at the girl.

“Yes,” said the boy.

“Nice.”

“Hey, Calvin, you leave them alone,” the girl named Tiwanda said from behind the seat. Calvin looked startled and disappeared abruptly.

“Hey, man, what you do that for? I was just saying how do you do.”

“Leave them alone, you hear?”

The black girl stuck her head over the seat. She had small delicate ears with gold earrings.

“Here,” she said, pushing a can of Coke into the girl's hands.

“Thanks,” said the girl.

“That's okay. It's warm.” Tiwanda waited until the girl had opened the can and taken a sip. Then she sat back, looking satisfied.

The boy and girl took turns drinking out of the can. It was the first time she had ever shared a glass or a can with someone other than her mother, actually putting her mouth on the same place. It meant that she was getting his germs. She was getting his germs; he was getting hers. She didn't mind. If they had the same germs, she reasoned, they would be all right.

It was warm on the bus. The air smelled of hot plastic and the sweet rich smell of the stuff that some

of the black kids put on their hair. He felt very tired. He wasn't hungry anymore. Just tired.

of the black kids put on their hair. He felt very tired. He wasn't hungry anymore. Just tired.

The girl was drifting into sleep beside him, leaning against his shoulder. He turned his head carefully and smelled her hair. He could smell the lake and something spicy and private underneath.

“What are you doing?” she said.

“Smelling you.”

“Boy, you're gross,” she said comfortably, not taking her head away.

When she was asleep he let his head loll back against the seat so that he could look out the side window. The bus flashed over a bridge and he caught a glimpse of a stream rushing down a hillside over dark rocks and black fallen trees. He thought he saw something moving there. A deer, maybe, with heavy branching horns, running in the same direction the bus was going. He would have sat up, but he was tired, and he didn't want to disturb the girl's head on his shoulder. It was too late to see anything, anyway. Perhaps he would see the deer later.

He began to think again of what it would be like for them to live alone somewhere in the woods. Like deer. People didn't see deer very often, unless they came down out of the woods. They would need supplies. Blankets and things. An ax or something to cut wood. He remembered the cottage where he had broken in. There were other cottages. They could probably find in them everything that they needed. They would keep track of what they took, of course.

Perhaps they could even leave a note with their names. People would know they were out there, somewhere in the woods, but they wouldn't be able to find them. They could build a shelter in some hidden place: a cave, a tangle of trees knocked over by storms. Or maybe it would be best to keep moving, building small, smokeless fires at night. He was good at that sort of thing. At Indian lore. It was about the only thing he had liked at camp. It wouldn't be so hard. Not as hard as going back to camp. Winter, of course, would be more difficult. He could see the girl, dressed in clothes the color of fallen leaves, the smile at the corners of her mouth. He drifted into sleep, his imagination absorbed in dreams of them surviving alone.

Perhaps they could even leave a note with their names. People would know they were out there, somewhere in the woods, but they wouldn't be able to find them. They could build a shelter in some hidden place: a cave, a tangle of trees knocked over by storms. Or maybe it would be best to keep moving, building small, smokeless fires at night. He was good at that sort of thing. At Indian lore. It was about the only thing he had liked at camp. It wouldn't be so hard. Not as hard as going back to camp. Winter, of course, would be more difficult. He could see the girl, dressed in clothes the color of fallen leaves, the smile at the corners of her mouth. He drifted into sleep, his imagination absorbed in dreams of them surviving alone.

Â

He woke up when the bus turned off the highway onto a gravel road. The headlights swept over a weedy verge coated with dust and a sign that said Camp something or other. It was gone before he was able to read it. The girl was still asleep, leaning heavily against his shoulder.

They had drawn quite close to the other bus. Its square yellow back and glowing taillights filled the windshield. Some kids were smiling and making gestures out the window in the rear emergency door. He couldn't understand what they were trying to tell him. It couldn't be important, he decided.

The buses followed the road a long way, descending into narrow ravines filled with mist and climbing out again in low gear. They made a number of turnings

and occasionally would cross another minor road. At first the boy tried to keep track, but after a while he gave up. It was going to be hard to find their way back to the highway. Perhaps they wouldn't be able to. He wasn't sure that it mattered.

and occasionally would cross another minor road. At first the boy tried to keep track, but after a while he gave up. It was going to be hard to find their way back to the highway. Perhaps they wouldn't be able to. He wasn't sure that it mattered.

The bus finally stopped in front of a long low building. Over the double screen door was a single light bulb, around which pale, fragile insects were swarming.

The bus driver turned off the engine and began flipping switches. The bus was filled with harsh light. The girl sat up and stretched, and then hunched over, shivering slightly.

“Where are we?” she whispered.

“I don't know. It's a camp of some sort. We'll get off when the other kids do and then just walk away. It's dark. Nobody will notice.”

She nodded and leaned forward, trying to see out into the dark through the reflection in the windshield of kids crowding the aisles.

The bus driver had cranked open the door, and the smell of pines welled up the steps.

“Everybody stay in your seats ⦠Stay in your seats!” he repeated in a loud voice. “Mr. Carlson will tell you when you can get off. We don't want people wandering around and getting lost.”

“Hey, man. How long?” someone asked. “I'm about to piss myself.”

The bus driver looked as if he might say something,

but then he got off the bus, fumbling in his jacket for his cigarettes. The boy and girl sat still, listening to the kids talking and laughing behind them.

but then he got off the bus, fumbling in his jacket for his cigarettes. The boy and girl sat still, listening to the kids talking and laughing behind them.

After a few minutes the man with the clipboard bounded up the steps.

Other books

Far From Home by Ellie Dean

How Beautiful It Is and How Easily It Can Be Broken by Daniel Mendelsohn

The President's Daughter by Jack Higgins

Creation by Greg Chase

The Mammoth Book of Best New Science Fiction: 23rd Annual Collection by Gardner Dozois

Duplicity (Spellbound #2) by Jefford, Nikki

Landon's Desire (Book Three of The Pulse Series 3) by Rose, Jennifer

Master of Bella Terra by Christina Hollis

Rebecca Wentworth's Distraction by Robert J. Begiebing

Summer Sky by Lisa Swallow