The Goats (10 page)

Authors: Brock Cole

“How could we forget anything? We don't have anything to forget.”

That was true. There was nothing left in the room that might be associated with them. And yet he had a strong sense that something had been overlooked. It must be simply nerves, he decided.

They closed the door behind them and walked boldly together down the row of empty rooms and out through the passage toward the highway.

Â

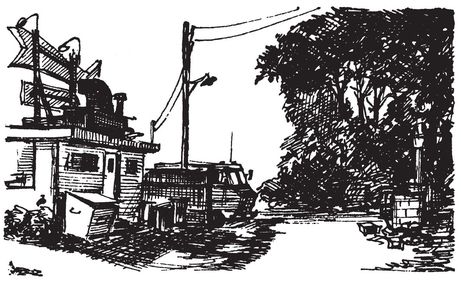

Barnesville was small and empty, with a main street too wide for the traffic. The sidewalks were cracked and littered with chips of concrete and dust from the road. It didn't look as if anyone ever walked on them. Most of the old brick storefronts were empty. There was a photography studio that someone had opened beneath a granite façade that said FIRST NATIONAL BANK, and they stopped and looked in the windows.

Behind the dusty glass were highly colored photographs

of people getting married and high-school students with flat caps on their heads. The girls had round shiny faces, and the boys too much hair. In the center of the display was a large photograph of a young man in a Marine uniform. He had small, sly eyes and was smiling. Underneath was a sign with a black border that said FOR GOD AND COUNTRY. The boy thought it meant he was dead.

of people getting married and high-school students with flat caps on their heads. The girls had round shiny faces, and the boys too much hair. In the center of the display was a large photograph of a young man in a Marine uniform. He had small, sly eyes and was smiling. Underneath was a sign with a black border that said FOR GOD AND COUNTRY. The boy thought it meant he was dead.

At the end of the main street was a new shopping center. Cars and pickups were parked outside a Jewel supermarket and a Firestone tire store.

The girl stepped in front of the boy so abruptly that he almost ran into her.

“You wait here,” she said. “I have to buy something.”

“What?”

“A comb and some stuff.”

He didn't understand what she was talking about. “But we've only got about four dollars.” It was all that was left from the five dollars that Tiwanda had lent them. They had had to break it so that they could leave a message for the girl's mother. “We need it for food.”

The girl twisted around impatiently and stared out over the parking lot.

“This is more important,” she said.

“I don't get it. What are you talking about?”

“Listen. Give me the money. I don't have to tell you everything.” She was frowning and trying to sound angry, but she wasn't succeeding.

“It's for girls,” she said, and turned dark red under her tan.

He thought he understood then. Not exactly. It had to do with that business that Miss Crandell had talked about in health class. He hadn't paid much attention. It had all seemed so unlikely and, well, awesome. He hadn't been able to connect it in his head with the girls he knew.

“Oh. Yeah,” he said, and gave her the money. While she went inside, he sat down on a mechanical rocking horse by the door. He wondered if Indians had had this problem before there was civilization and everything. They were people, so they must have had to do something. But when they were living in the woods they couldn't just run down to the Jewel. It was an interesting question and he would like to discuss it, but he didn't think she would want to right now.

When she came out she had a package in a brown paper bag, but she didn't offer to show it to him.

“I bought some bananas, too,” she said.

“Oh, that's great. I'm getting hungry. Are you?”

She nodded. “Starving. There's a gas station over there. I have to go there now.”

This time he didn't ask why.

While the girl was in the ladies' room, he studied a map that someone had pinned up over the cash register. A mechanic who was working underneath a car on a hoist leaned over so that he could watch him through the door, but the boy pretended not to notice.

After a minute the mechanic put down his wrench and came into the office.

After a minute the mechanic put down his wrench and came into the office.

“You want something?” he asked.

“I just wanted to see where Ahlburg is,” said the boy.

“Here,” said the man. He pointed with a blackened finger at a spot on the map. It was hard for the boy to look at it with the man watching him.

“Is that far?”

“About eight miles. Highway 41. That's this road right here. Okay?” The man was waiting for him to go away, so he went outside to stand in the road. He looked down the highway in the direction he thought Ahlburg must be. Eight miles wasn't that far. If they woke up early they could walk it and be in the camp parking lot before noon. This time tomorrow they might be driving in the girl's mother's car back to the city. It seemed so simple that it made him uneasy.

They ate their bananas in a park behind the supermarket. It was small and dusty, with a large cottonwood in the middle and a rickety swing set in one corner. They sat on a picnic table and watched three little boys race around a dusty track on BMX bicycles. Someone had piled up a mound of dirt in the center of the track, and when the boys hit it, they jerked their bicycles high into the air. They seemed to want to fly away, right out of Barnesville.

The bananas were greenish and bitter, but they ate them slowly to make them last. When they had finished,

it was still too early to go back to the motel, so the boy got out the small brown notebook that he had found in his pants and they made a list of the things they would have to come back and pay for.

it was still too early to go back to the motel, so the boy got out the small brown notebook that he had found in his pants and they made a list of the things they would have to come back and pay for.

The girl had memorized Tiwanda's address in the city, but the boy wrote it down just to be sure. The five dollars was a loan, and they would have to pay it back. They weren't sure at first what to do about the other stuff the kids at the camp had given them. There was underwear for both of them; Lydia's red shirt, which was probably expensive; and the toothbrush. They decided finally that it would be rude to try to pay them back for these things. Instead they should get them something nice as a present. Maybe even a portable radio to take with them when they went camping again. It would be great if they could do that.

Then they listed the things they had borrowed without asking. It was surprising how much there was. There was first of all the cans of soup and fruit cocktail from the cottage. And the clothes: two T-shirts, a sweat shirt, and a pair of pants. They would also have to pay for the damage to the shutter on the window. They didn't think they should have to pay for the saltines and the ginger ale. Nobody would have eaten them if they hadn't. Still, they decided that they wouldn't act as if it was a big deal if someone asked them to pay.

Thinking about the clothes they had taken from the bathhouse made them both nervous. The blond

boy and his girlfriend probably wouldn't want them back now, even if they were washed. It would be embarrassing to have to meet them, anyway. They decided they would just send a money order if they could find out their names. Perhaps the guy at the concession stand would know.

boy and his girlfriend probably wouldn't want them back now, even if they were washed. It would be embarrassing to have to meet them, anyway. They decided they would just send a money order if they could find out their names. Perhaps the guy at the concession stand would know.

It didn't seem likely that they would ever find the people who owned the pickup with the roll bar, where the girl had taken the change, but they wrote it down anyway because it seemed right. “Pickup: $1.40.”

The motel room was going to be expensive. The boy thought it might cost over fifty dollars. The girl looked stunned when he told her.

“Boy,” she said. “My mom's going to have kittens.”

“That's okay. My dad will pay for it, I think. I mean, when I tell them what happened.”

“Really? They won't be mad because we didn't go back to camp?”

The boy thought about it. No, they wouldn't be mad, exactly. His father would be baffled and upset. It would be like when he failed algebra. He could remember his father standing in the kitchen doorway, watching him while he pretended that he knew what he was doing with his homework. His father had looked so upset and, well, helpless. He had felt awful.

It would interfere with his father's work. That was the bad part. Everyone would be miserable, and his mother would sigh and look at her hands in that funny way that meant he had let them down again.

“No,” he said. “They'll just feel bad. I always make them feel bad.”

The girl was puzzled. She thought of her own mother, who cried a lot and sometimes said things she didn't really mean. She supposed her mother was feeling bad when that happened. But she didn't think that was what he meant.

“Why?” she asked.

“I don't know. They're kind of old. I think it was a shock when I got born. I was an accident, maybe.”

He had never told anyone this before, but he believed it. It would explain why he never seemed to fit into his parents' life. They loved him, and they wanted him to be happy, but they didn't know what to do with him. He had to be careful not to get in the way. It had made him watchful.

The girl leaned forward so she could turn and look up at his face.

“Does that make you sad?”

It was an embarrassing thing to be asked. He wanted to giggle and shiver at the same time. He didn't know what to say.

“I don't know. What do you think?”

She folded up her banana peel neatly in her hand. “Well,” she said, “I think it means we have luck. I mean, you might not have been born, but here you are. That's lucky, isn't it?”

He looked at her dark eyes and her wide mouth with the turned-up corners.

“Yes,” he said. “That's lucky.”

WHEN THEY got back to the motel, they found the beds had been made up with clean sheets, and fresh white towels had been piled on a chrome rack by the shower. There was even a paper band around the toilet seat that said it had been sanitized for their protection.

The girl decided that they should take showers. He didn't much feel like it, but she insisted. Neither of them had washed their hair or feet since they had left the island.

The boy went first. When he had finished he felt lightheaded, and his nose and throat were parched. He drank two glasses of water and got into one of the beds with his clothes on.

“Hey,” said the girl, who was studying the plastic laminated sheet on top of the television. “They have adult movies. Do you want to watch an adult movie?”

“What is it?”

“

Chaste Coed

. That's a joke, I think.”

Chaste Coed

. That's a joke, I think.”

“Gross.”

“Yeah. You have to pay extra at the office to have it hooked up,” she said after a moment's further study. “So I guess that's out. There's a Benji movie. You want to see that? We don't have to pay.”

He nodded and she turned on the television. Then she went in the bathroom to take her shower.

He lay in the bed with his eyes closed and listened to the television. It was funny: before, he had felt hot, and now, under the covers, he felt cold. He thought about the chased coed. He couldn't see what the joke was.

When the girl was finished with her shower, he watched her comb out her hair at the dresser. Her red shirt clung to her pointed shoulder blades as she raised her arms.

The light of the late-afternoon sun shining through the curtains made the room seem like a burrow. A hiding place. She had been right. It was better to stay there than to run around in the woods, he told himself. But the faint uneasiness that he had felt earlier refused to go away. There was something they had overlooked, but his cold made it too hard to think what it was.

When the girl's hair was combed out, she wrapped

it in a towel on top of her head. He had never seen anyone actually do this. It gave him pleasure to watch the casual, deft way in which she did it. He wondered if he would ever learn everything there was to know about her. When she brushed her teeth, she spit out in the toilet and not in the washbowl. That was interesting.

it in a towel on top of her head. He had never seen anyone actually do this. It gave him pleasure to watch the casual, deft way in which she did it. He wondered if he would ever learn everything there was to know about her. When she brushed her teeth, she spit out in the toilet and not in the washbowl. That was interesting.

“What's happening?” asked the girl.

“What?”

“On the television.”

“I don't know. I was watching you.”

“Creep,” she said, grinning at him in the mirror.

She walked over to the bed and looked down at him. “Why are you shivering? Are you cold?”

“Yeah. I can't seem to get warm.”

“Shall I get in bed with you?”

“Yes, please.”

She kicked off her shoes and got under the covers. She piled up the pillows so that she could sit up and hold him against her as they watched the movie. After a while he stopped shivering.

For some reason the movie was difficult to understand. Perhaps it was because they had missed the first few moments or because it had been cut in some way. It all seemed very peculiar. A blond girl and a boy in neat polyester clothes were being chased by a man with slick black hair. Or perhaps they weren't being chased. They never got dirty. They were never out of breath or hungry. They were excited about something, but they didn't seem to be afraid.

Benji was being chased, too, by a large Doberman. Every now and then he did something cute. The movie would stop for a minute so everyone could see what a cute dog he was.

“I don't get it,” said the girl after a few minutes. “Do you?”

The boy shook his head. “It's funny, because I think I saw this movie before.”

“Yeah, me too. I didn't know it was so boring. Did you know it was so boring?”

“No. I thought it was great, but I was just a little kid, then.”

The girl got up and turned off the television. “Tell me some more about Greece,” she said, flopping down on the bed again. “Not the cave. Some nice stuff.”

“The cave's nice.”

“No, it isn't. I mean, it's not bad, but it's so weird. Tell me about some stuff that isn't so weird.”

The boy thought for a minute. “Well, once my dad and I walked all the way from Delphi to the sea. I think that was about the best day I ever had.”

“Until now,” said the girl so quickly they were both surprised. She turned red, but he nodded.

“Until now.”

“What was so special about it?” she asked, trying not to sound too interested.

“I don't know. Partly it was doing something with my dad. He was so busy we didn't do much together. Lots of times I would just sit around in hotels and

read comics. But we went on this walk for some reason. I forget why.

read comics. But we went on this walk for some reason. I forget why.

“We didn't walk on the road. We walked straight down the mountain and through this great grove of olive trees. It was a sacred wood. Back in ancient times. If you killed anything there, that offended the god.”

“Was that the god in the cave?”

“I don't know. Maybe. You want to hear something crazy?”

“What?”

“While we were walking in the wood I got this strange idea that he was still there. That's crazy, isn't it?”

“Yeah, sort of. It's weird. Didn't you do anything there that wasn't weird?”

“No, listen. It wasn't weird. I was so happy. Everything was so clear. Do you remember when you first got glasses? When you put them on and you could see?”

“Yeah, I remember that. I read all the street signs when I rode home on the bus from the eye doctor. I read them all out loud. My mom thought I was nuts. I must have thought nobody can read street signs.”

“Well, that's what it was like. Only it wasn't just street signs. It was everything. I'd look at a tree, and Oh wow, I'd say. So that's what a tree is. And then I'd look at a leaf ⦔

“And you'd say, Oh wow. That's a leaf.”

He was so goofy he made her laugh.

“It's really true,” he insisted, but laughing as well. “I could smell everything, too. The sea, the dry grass. Even the sun.”

“Come on. What does the sun smell like?”

“It smells like fire. Like a charcoal fire when you can't see the flames anymore.”

“No, it doesn't. You know when you've been swimming and you lie down all wet on the float and stick your nose against the wood? That's what the sun smells like.”

“Yeah. That, too.” He smiled at the ceiling, drowsy and happy. “We followed a river for a while. It was dry. Nothing but white stones. It hurt your eyes to look at it. A river of bones. I wanted to stay there forever.”

The girl picked up his hand and studied it, curling up his fingers with hers one at a time.

“Do you think we could go there sometime? I mean together?” she asked. She touched the palm of his hand with the tip of her tongue experimentally.

“Hey. That feels funny.”

“Hey, yourself. Do you think we could?” She held up their hands palm to palm. Her fingers were longer than his.

“Of course. We can if we want to. We may have to wait until we're, you know, older.”

“Oh yeah, I know that. But we could if we want to. If we don't all get blown up or something.”

She suddenly flopped over on her back so that her turban fell off. She didn't seem to notice.

“Do you know something?” she asked.

“What?”

“I should have asked you before, but I didn't.”

“What? Tell me.”

She took a deep breath and held it for a second. “I don't know your name,” she said all at once. She covered her face with her hands and looked at him through her fingers. “That's pretty stupid, isn't it?”

“No, it isn't. It's kind of a stupid name, though. It's Howard. Howie. Your name's Laura, isn't it? I didn't remember at first, but then I did.”

“Yeah. Laura Golden. But you want to know something else? That's not my real name. Did you know that?”

“No. What is it?”

“You promise you won't tell?”

“Yes, I promise.”

“Then it's Shadow. Isn't that a weird name? It's on my birth certificate and everything.”

He laced his fingers over his stomach, considering. “Shadow Golden.” He pronounced it very carefully. “I think it's kind of neat.”

“Yeah. My mom and dad thought they were going to have a boy, and they were going to call him Sun. You know. S-U-N. It was supposed to be this really subtle joke, but they had me instead.

“They were hippies. My dad still is, but we don't

see him anymore. He took a lot of drugs and did something to his brain.

see him anymore. He took a lot of drugs and did something to his brain.

“You know something else?” She propped herself up on one elbow so that she could look at him. She was getting excited. “I was almost born in a tepee. They were going to have this big party and natural childbirth and everything. But there were complications, so I got born in a hospital. God, my mother would die if she knew I was telling you all this stuff. My mom, the hippie. Can you believe it?”

“Yes. She's probably okay.”

“Yeah, she is really. She changed my name when I started school. She was afraidâyou knowâthat I'd have problems.”

“It's still your name. Sort of a special name.”

She turned toward him suddenly, so that the wet ends of her damp hair swept his cheeks.

“Do you have any secrets?” she asked.

“I don't know. I don't think so.” He tried to think. Sometimes he felt as if he was all secrets, but he didn't think there was anything he wouldn't tell her. Well, there was one thing. He hadn't told her about his idea of just the two of them living together in the woods. He wanted to tell her now, but he was afraid to. He wasn't afraid that she would laugh at him anymore. It wasn't that. He was afraid that it would lose some of its magic. That it would just sound queer.

“There is one thing. But I can't tell you yet.”

“You can't?” She was disappointed.

“No. It's because it's about you and me. There has to be this special time when I tell you.”

“Well. Will you tell me? Sometime?”

“Of course. I promise.”

The time would come. Perhaps it would be tomorrow afternoon at her mother's apartment in the city, but that wasn't what he pictured. He saw them walking together up a road into the woods. The sun was shining and birds were singing. It was an old road, overgrown with grass and small trees. Soon it would disappear altogether. It didn't matter. They weren't coming back that way.

Â

When they woke up they were starving to death. The girl got out of bed and peeked out through the heavy curtains.

“Hey,” she said. “It's not even dark yet. What are we going to do?”

“I don't know. How much money have we got left?”

She went through her jeans pockets.

“Thirty-eight cents,” she said, holding the money in the palm of her hand for him to see.

“We can get a candy bar. I mean, we won't actually starve to death, anyway. It's just until tomorrow.”

“I wish I'd saved that banana peel,” she said, sitting down on the bed and looking desolate.

“Why? You can't eat banana peels.”

“I guess not, but I'm really hungry.” She was so

skinny and couldn't get enough to eat. It made him want to do something.

skinny and couldn't get enough to eat. It made him want to do something.

Other books

Audrey's Promise by Sheehey, Susan

Coming to Rosemont by Barbara Hinske

Artful Dodger (Maggie Kean Mis-Adventures) by Davis, Nageeba

Fire on the Horizon by Tom Shroder

Uncontrollable by Shantel Tessier

The Usurper by John Norman

Wicked by Any Other Name by Linda Wisdom

Dangerously Broken by Eden Bradley

Los santos inocentes by Miguel Delibes

Cameo the Assassin by Dawn McCullough-White