The Girls from Ames (40 page)

Read The Girls from Ames Online

Authors: Jeffrey Zaslow

The girls who attended the funeral recall how they stood at the grave site after the memorial service. It was mid-March, but given Iowa’s weather, it was still extremely cold. “When it was over, everyone left—the family, the adults—and we stood there,” Sally says. “I remember it was a very powerful moment, just standing there. It must have been ten minutes. We didn’t say anything.”

As the girls talk about Sheila, a few of them hatch an idea. What if they pooled some money—they’ve got resources now that they didn’t have when they were younger—and established a scholarship at Ames High in Sheila’s memory? It could be given to a female student who was kind to everyone, who was well liked—someone who was a good friend to other girls.

The winner shouldn’t be selected by teachers or administrators, the girls decide. “She ought to be nominated by her friends,” Karen says.

The girls are completely enthusiastic about creating a Sheila Walsh Scholarship. They picture this new generation of Ames girls thinking about the qualities that define a good friend.

They say they’d love to meet the winner of the scholarship: what a terrific and giving girl she’d likely be. No doubt someone just like Sheila.

18

North of Forty

O

n the way back from dinner in Raleigh, the girls are traveling in two cars, one following the other. Suddenly, the first car makes an abrupt U-turn. Did they take a wrong turn? Did someone forget something back at the restaurant?

n the way back from dinner in Raleigh, the girls are traveling in two cars, one following the other. Suddenly, the first car makes an abrupt U-turn. Did they take a wrong turn? Did someone forget something back at the restaurant?

“What’s going on?” Marilyn wonders in the second car.

A cell phone rings in car number two. A few of the girls in the first car, driven by Angela, are calling to say they have made a decision. They’ve spotted a sexy lingerie store on the side of the highway and they’re pulling into the parking lot. They want to look around. Maybe they’ll find something fun.

There are a few groans in the second car. Some of the girls are tired. Some are just feeling their age. They have no great urge to go browsing in a lingerie store.

The two cars pull side by side into the store’s parking lot and the girls talk to each other through open windows. Kelly, Diana and a few others say they’re up for going in. But the rest aren’t especially interested. The majority vote no.

“OK,” says Angela. “We’ll just go back to my house.”

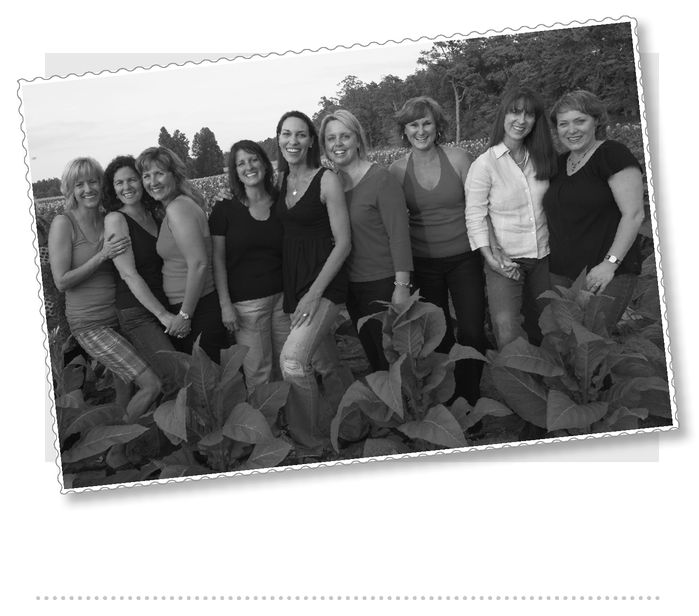

The tobacco fi eld behind Angela’s house, 2007 (left to right): Diana, Jane, Karen, Marilyn, Karla, Sally, Kelly, Jenny, Angela

The cars drive away, and Kelly says something about “wet blankets” and “party poopers.” Even the girls who were intrigued by the idea of going inside this naughty store surrendered awfully easily. “You’re big talkers,” Kelly says, “with granny underwear in your suitcases.”

T

he days of piling into cars and going to cornfield keggers feel long ago for these women. They can’t picture themselves exactly in that same party-time, adventure-seeking frame of mind they had back in high school. Some of what’s at play here is just maturity. A woman in her forties doesn’t have the same sense of fun as a girl in her teens. But much of it, of course, is also the result of where life has taken them. The laughs still come in huge bursts. But in adulthood, there have been a lot of sobering moments, too—a lot of emotion-stirring places they’ve been together. Those images are often clearest in the girls’ heads.

he days of piling into cars and going to cornfield keggers feel long ago for these women. They can’t picture themselves exactly in that same party-time, adventure-seeking frame of mind they had back in high school. Some of what’s at play here is just maturity. A woman in her forties doesn’t have the same sense of fun as a girl in her teens. But much of it, of course, is also the result of where life has taken them. The laughs still come in huge bursts. But in adulthood, there have been a lot of sobering moments, too—a lot of emotion-stirring places they’ve been together. Those images are often clearest in the girls’ heads.

Two years after Christie died, for instance, Diana flew into Minnesota, and she and Kelly stayed at Karla’s house on a night Bruce was out of town. Diana and Kelly slept in Christie’s room, which had remained little changed from the day she last slept in it. Her doctors had allowed her to come home for her fourteenth birthday, so she could be with her family, and that was her final night in the bedroom.

Karla had preserved the room pretty much as it was; she hadn’t rearranged anything. She told Kelly and Diana that there was no comfort in seeing that empty bedroom every day, but she couldn’t bring herself to alter it.

Diana and Kelly didn’t talk much about Christie in the bedroom that night. Each of them wondered if they’d feel Christie’s presence, but they didn’t articulate this. “I was both afraid and honored to be staying in her room,” Kelly told Diana the next morning. “I guess I wanted Christie’s spirit to visit me, to tell me she was OK.”

On a different trip, Cathy and Sally slept in Christie’s room when visiting Karla, and they had that same sense of wanting to feel a connection to her. The room was dominated by a large and lovely poster-sized photo of Christie with her best friend, Jessie. The poster, a gift from Jessie, hung over the bed and included the words “Friends Forever” in big type. And so the room spoke about both loss and friendship.

Karla confided in the other girls about her “sad time”—starting with the Christmas holidays and continuing through Christie’s birthday on January 9 and the anniversary of her death, February 20. Karla explained how her family tried to remember Christie in upbeat ways. They had taken her to P. F. Chang’s, a Chinese restaurant, for her last birthday. So Bruce, Karla, Ben and Jackie returned to the restaurant on the January 9 after Christie died. They had dinner and then went back to their house for homemade Funfetti cupcakes, which were Christie’s favorite, just as they had on her birthday.

The Ames girls continued to be impressed and moved by how supportive Bruce was of their friend Karla. Karen couldn’t get out of her mind the day of the funeral, when Jane held Bruce’s hands and said to him, “This must be the hardest day of your life.” Bruce paused, then responded, “No, the hardest day was the day Christie was diagnosed.” In his answer, the girls felt as if they’d gotten a look into the depth of his pain and his love for Karla. The hardest day of his life had been ongoing.

The girls considered Bruce to be one of the most giving husbands they had ever observed, and that was well before Christie was sick. There was one gathering years earlier at Karla’s house. Bruce volunteered to sack out on the family’s boat with the kids for a couple of days so the Ames girls could have the full run of the house. Then he spent a day driving them all around in the boat—pointing out landmarks, making everyone lunch, getting them all drinks. “He’s a one-in-a-million guy,” Karen liked to say.

Bruce, while nursing his own grief, also knew to give Karla space and time, and to support her as she struggled to find coping rituals. For a long while, Karla would touch Christie’s ashes on the mantel before going to bed, just to say good night. She said she liked talking about Christie, but struggled to focus on “the happy years.” Too many harder memories crowded things out. There were too many reminders around the house, on the street, around the community.

People would nonchalantly ask, “How many children do you have?” and Karla would usually say “three,” and explain. To avoid questions, a few times she said, “two,” and then felt too guilty afterward. “It’s not fair to Christie not to mention her,” she told the other girls.

The decision to move out of Minnesota crystallized for Karla when she was in bed one February morning, three years after Christie’s death. It was President’s Day, the kids had off from school and Bruce was at work. Their daughter Jackie crawled into bed with Karla and started talking about one of the horses that the family owned. They kept horses in a stable thirty-five minutes from their house. “Wouldn’t it be great if I could wake up every morning and kiss my horse on the nose?” Jackie said to Karla. “I could just roll out of bed in my pajamas and go give a big kiss.”

Bruce’s family had land in Bozeman, Montana. His great-grandfather was the homesteader there in the late 1800s, and there was a barn right on the property. Karla figured the time had finally come: Why not just move there?

“Call your dad,” Karla told Jackie. She dialed Bruce, he voted yes also, Ben did the same, and the decision was made. Yes, it would be painful to leave Christie’s bedroom, and all those memories, good and bad, behind. But it could be the best thing for Karla, Bruce, Jackie and Ben. And the horse might just like being kissed first thing in the morning.

“Part of me can’t imagine leaving Minnesota, and living in a place where people never knew Christie,” Karla admitted to Marilyn and Sally one day when they came to visit. She told them of a bracelet Jackie wore with Christie’s initials: CRB. Jackie had the bracelet on one day when she was at a medical appointment, and a woman working in the office asked, “What does CRB stand for?”

“It’s for my sister,” Jackie told her.

And the woman said, “Oh, yeah. That’s right. You had a sister who died.” The woman said nothing else, just moved on to the next item of business. “A lot of people are nervous or don’t know what to say,” Karla later told her friends. “But I really felt for Jackie in that moment. It’s hard for kids, when people just gloss it over, when they don’t really acknowledge her loss.”

In Montana, where no one knew Christie, there might be even more glossing over, Karla said. Moving there could be hard for the family in ways they couldn’t even fathom. And yet a strong part of Karla knew the decision to go was the right one for her and her family. And in her heart she knew: Christie would understand.

“After losing her,” Karla said, “we’ve been learning not to wait until tomorrow to do anything.”

In their forties, several of the other girls also opted to take an inventory of their lives and to embark on new journeys. Cathy made plans to cut back on her work as a makeup artist and to focus more on screenwriting. Marilyn thought she’d get into singing and acting in community theater, tapping back into talents she’d nurtured earlier in her life. Karen felt herself getting closer to a return to teaching, and that wasn’t all that was new for her. As she liked to put it, jokingly: “If tomorrow’s Monday, I’m starting a new diet!”

In middle age, the Ames girls’ interests took turns they never would have predicted earlier in their lives. Angela, for instance, who had built a successful public relations business in North Carolina, decided to start a second business, Finality Events.

It would be a special-events planning company to help people create “unique life celebrations” to help them remember those who’ve died. She was motivated by the loss of her mother in 1995 and her brother in 1999, and by watching Karla cope with Christie’s death in 2004. In the case of her mom and brother, especially, she felt they didn’t get the life celebrations they deserved. “The minister who tried to talk my brother out of being gay ended up being twenty minutes late for the service,” Angela told the other Ames girls. As a business model, she figured she was on to something: Baby boomers would want a memorable way to be remembered when they died.

Finality Events would help families identify the unique aspects of a loved one’s life to commemorate. Her staffers would write a “life remembrance story” that would be more than an obit. She planned to market the service to people who may have turned away from organized religion. She hoped to get it started in 2009.

Meanwhile, Diana felt surprisingly fulfilled in her forties, and that included her decision to take the job at Starbucks. She had always admired her mom’s career as a dietician, and she went to college knowing she would also have a serious career. She moved to Chicago to get the big-city experience she never had growing up in Ames, and she enjoyed being a CPA. But at age thirty-one she had her first daughter, and she soon experienced feelings she’d never anticipated. She went back to her job, but spent the day worrying about her baby. After work, she’d drive eighty miles an hour to pick her up. She soon quit her job and was an at-home mother for thirteen years. “Marriage and family were never high on my list of priorities when I was in my twenties,” she’d tell the others. “Isn’t it funny how those two things are now the center of my life?”

As her three daughters got older, she was happy to find the job at Starbucks. The hours were good, there wasn’t a lot of stress, and the fact that her whole family could get medical insurance through Starbucks was a major perk. Plus, most every customer came from a different line of work, which Diana found intriguing. “I see life beyond Mommydom,” she told Kelly. “It’s just the right job for right now.”

Diana also started thinking more clearly about ways in which “giving back” could be a part of her daily life. As she put it: “Every little step you take in showing kindness, volunteering at school and church, listening to others and sharing a smile at Starbucks—I think that all helps the world.”

She became more passionate about the environment. She helped set up a recycling program at her Starbucks. She began driving a hybrid vehicle, a Prius. And she dreamed of someday living in a green house.

B

y their mid-forties, women know they’re at a crossroads. They are still holding on to their younger selves, but they can also see their older selves pretty clearly.

y their mid-forties, women know they’re at a crossroads. They are still holding on to their younger selves, but they can also see their older selves pretty clearly.

“I’m proud of my gray hairs,” Cathy tells the other girls gathered at Angela’s. “Every four weeks, I say, ‘I’m proud of you!’ And then I cover them up.”

Other books

A Million Tears by Paul Henke

Alice by Judith Hermann

Taken by Storm: A Raised by Wolves Novel by Barnes, Jennifer Lynn

Beyond the Laughing Sky by Michelle Cuevas

Deep Pockets by Linda Barnes

Escape 2: Fight the Aliens by T. Jackson King

The Academy by Laura Antoniou

Wicked Fall by Sawyer Bennett

Ecstasy in the White Room by Portia Da Costa

It Is What It Is (Short Story) by Manswell Peterson