The Girls from Ames (39 page)

Read The Girls from Ames Online

Authors: Jeffrey Zaslow

Sheila’s family described her as being completely devoted to the other Ames girls. If someone made a crack about, say, the weight of one of her friends, Sheila would respond sharply. “She was intensely loyal,” said Susan. “If you were in her inner circle, she would jump off a cliff for you.”

The Walshes smiled and laughed over many of their memories of Sheila. They remembered when she and some of the other Ames girls did neck exercises, twisting and stretching their necks so they wouldn’t get wrinkles.

Susan said she and Sheila were sometimes very close, and other times, there was distance—or they fought. Though they were only eighteen months apart, they traveled in different circles of friends, especially as they got older. Sheila had told the other Ames girls that it was hard to live in Susan’s shadow, because Susan was so beautiful and accomplished, and got along better with their mom. Susan now understands some of the dynamics. “I was a rule-follower,” Susan said, “and Sheila wasn’t.”

They shared a room, and Susan has sweet memories of late-night conversations and of games they played as little girls. One was a convoluted “how hot are you now?” game they’d play by adjusting the settings on each other’s electric blankets.

“There’s something about losing a sister,” Susan said. “It’s like losing a part of yourself. In a lot of ways, she made me feel good about myself.” She added: “Each of us has put our memories of Sheila in a sort of protective, separate compartment, deep down inside somewhere.” It was emotional for them to be talking again so openly about her.

Sheila was headstrong. When Mrs. Walsh took the girls clothes shopping, she said, “Susan had this tall, thin figure and was easy to fit. Sheila was harder. And she always wanted something that didn’t look good on her. So shopping trips could be ruined.”

The family was often reminded of how close Sheila was to Dr. Walsh. Mark said that as an early teen, he used to go on a five-mile race with his father, and Sheila sometimes pedaled along on her bike. The first time he outran his father, Sheila was very upset. “She was actually crying,” Mark said. “She asked me, ‘How’d you beat him with those little legs of yours?’ She just had this bond with him. She was Daddy’s girl.”

“She knew how to work him,” said Susan.

“To Sheila, he was a softy,” Mrs. Walsh added.

As a dentist, Dr. Walsh had a reputation of being very gentle when he put his hands in a patients’ mouth. He often had that same gentleness in how he dealt with his children, especially Sheila.

Susan and Sheila were in the same sorority at the University of Kansas—when Sheila was a freshman, Susan was a sophomore. For her twentieth birthday, Susan received $100 from her dad. He died two days later at age forty-seven of a heart attack, and Susan ended up using the $100 toward plane tickets for her and Sheila to go home for the funeral. On the plane that day, they both were very quiet, their faces pale, their eyes red from crying. Two young men on the plane noticed these two pretty, red-eyed girls and tried to hit on them. “Hey, what have you two been doing?” one of them asked.

“They assumed we were stoned,” Susan said. “It’s weird, the things that you remember about moments like that.”

After Dr. Walsh died, Sheila was grieving for herself, but also very concerned about how her mother was faring. “She was just so empathetic,” Mrs. Walsh said. “And she was such a good listener.”

Mrs. Walsh said she never went on a date after her husband died. She was too busy trying to raise five children on her own. She smiled at one memory of the weeks after Dr. Walsh’s death. She was with a friend in her bedroom, trying to figure out how much the family would have to live on after factoring in Dr. Walsh’s life insurance pay-out and any remaining proceeds from his dental practice.

“Oh my gosh,” she said to her friend after she finished her calculations. “We’re only going to have five hundred dollars a month. The mortgage is more than that!”

The women looked at each other. “I can’t believe that son of a bitch would leave you with just five hundred dollars a month,” her friend said.

Mrs. Walsh did some more figuring. She never was too good at math. Turned out, Dr. Walsh had made sure the family had $5,000 a month to live on. Because he sensed that he’d die young, like his father, he had made sure everything was in place.

W

hen Sheila went to Chicago in January 1986 to work for a semester interning as a child life specialist at a hospital, her brother Mark didn’t really know what that job was. Now that his son was receiving cancer treatment, he understood. Child life specialists offer emotional support, education and resources to families. They are trained to ease young patients’ fears. They look out for their siblings. “When Charlie is going to have a procedure, something where they need him awake and they’re going to hurt him, the child life specialist comes in with dolls or toys and distracts him. It helps. Sheila just loved kids, so I can really see her doing that.”

hen Sheila went to Chicago in January 1986 to work for a semester interning as a child life specialist at a hospital, her brother Mark didn’t really know what that job was. Now that his son was receiving cancer treatment, he understood. Child life specialists offer emotional support, education and resources to families. They are trained to ease young patients’ fears. They look out for their siblings. “When Charlie is going to have a procedure, something where they need him awake and they’re going to hurt him, the child life specialist comes in with dolls or toys and distracts him. It helps. Sheila just loved kids, so I can really see her doing that.”

Sheila loved the job and loved living in Chicago. Her family noticed a growing maturity about her. She was living in housing provided by the hospital, making new friends, and was also spending time with Bud Man, her old friend the Budweiser employee from Iowa. He was then living in Chicago.

Her family got the call that she had been in an accident early on a Sunday morning in March. It appeared she had fallen, they were told by someone at the hospital, and had suffered a subdural hematoma. That’s a traumatic brain injury in which blood collects between the outer and middle layers of the covering of the brain. It is caused by the tearing of blood vessels. Sheila was in a coma, but she was stable and doctors believed she would recover.

Mrs. Walsh flew to Chicago, and when she got to the hospital, Sheila was in bed. There was no visible injury from the fall. She looked peaceful, like she was sleeping. Doctors said she still had brain activity.

“Has she said anything?” Mrs. Walsh asked a nurse.

“She spoke just once,” the nurse said. “The only thing she has said was ‘My dad is coming to get me.’ ”

The nurse didn’t know anything about the family history, or that Sheila’s father had died four years earlier. Sheila had arrived at the hospital unconscious.

Mrs. Walsh was stunned to hear what Sheila had said. But over time, the family has taken comfort in knowing those were Sheila’s last words. “I believe our dad was coming to her to say it’s OK, it’s time to go,” said Susan. “It helps us to think they are together.”

Sheila lived for another two days, never regaining consciousness. By the end, when the family was told she had no brain activity and wouldn’t recover, they decided to donate her organs. Sheila had never mentioned that she’d want to be an organ donor, but given who she was, how she loved people, and how she always had this urge to help others, well, it was clear to the family that she’d agree with their decision. Her liver went to a dentist’s wife, which Mrs. Walsh felt was a fitting nod to her husband’s profession. Liver transplants were often unsuccessful in the 1980s, however, and the woman didn’t survive.

The family was told that Sheila’s organs went to seven people, but they were given no names. They read in the newspaper about a woman who was a teacher in Iowa City and received a heart/lung transplant the day after Sheila died. They assume that Sheila was the donor. This woman also didn’t survive long.

Someone received Sheila’s corneas, and the family likes to think that the recipient is still living and enjoying the view. “Sheila had beautiful eyes,” Susan said. “Really beautiful eyes.”

A

fter Susan arrived in Chicago on the Monday Sheila died, she and her mother tried to learn what had led to the accident. They talked to her friend Bud Man, who was understandably distraught. He said he and Sheila had been downtown in a bar, drinking. They had met some people there. Sheila and Bud Man got in a little argument and she said she was leaving.

fter Susan arrived in Chicago on the Monday Sheila died, she and her mother tried to learn what had led to the accident. They talked to her friend Bud Man, who was understandably distraught. He said he and Sheila had been downtown in a bar, drinking. They had met some people there. Sheila and Bud Man got in a little argument and she said she was leaving.

The people she met in the bar invited her to go to a party at a two-story brownstone elsewhere in the city, and she left with them.

Mrs. Walsh and Susan went to look at the house and talked to people in the neighborhood who had heard about the incident. The story the neighbors told was this:

Something happened at a party inside that house that made Sheila uncomfortable or upset. She got a little freaked out, the Walshes were told, felt she needed to get away and decided to go out on the balcony and then jump the short distance to the roof of the garage next door. She made it to the garage roof fine, but then she tried to climb onto the fence adjacent to it so she could get to the ground. She slipped and hit her head when she fell to the ground.

She was always kind of clumsy, Susan said, and it certainly didn’t help that it was dark, about 2 A.M. on a Saturday night, and that she’d been drinking.

When Mrs. Walsh and Susan stood by that fence, they could still see blood from where Sheila had hit her head. The police report was bare bones: A young woman slipped climbing off a fence, hit her head, and was taken to the hospital.

The Walshes were never able to find and talk to anyone who was actually inside that house that night. In their grief, they didn’t really try too hard. It was hard even to concentrate on the specifics of the incident.

And so the mystery of what made Sheila leave that gathering—and by the balcony, not the front door—was never solved. Perhaps it wasn’t as sinister as people might think, said Mark. “It wouldn’t have taken much for her to go off. Someone might have just said something and she got upset.” Susan’s take: “I don’t think she was being chased. I just think she realized she was in a situation she shouldn’t be in and she was trying to leave.”

Bud Man felt terribly guilty that he’d let Sheila leave him that night. The Walshes were understanding. They said Sheila could be impulsive. “Once Sheila made up her mind,” said Mrs. Walsh, “there wasn’t much you could do.” The fall and the way her head hit the ground “was bad luck, basically,” Susan added.

For years, the family found it hard to talk about the details of how Sheila died. That’s why the Ames girls, and most everyone else in town, never really heard the full story.

Just as the Ames girls speculate about what Sheila might be up to now had she lived, her family has also thought through the same what-ifs.

“I’d have been worried about who she’d marry,” said Mrs. Walsh. “She didn’t always make the best choices.” But as Mark sees it: “At the end of the day, she would have found the right guy and she’d be happily married with kids.” Added Susan: “I like to think she’d be living here in Kansas City with us. Maybe it wouldn’t have started out that way, but she’d come to be with us.”

Whether she’d have built a career as a child life specialist, she’d surely be a great presence in the life of her ill nephew Charlie. The family described him as a boy who is spunky, fun-loving, hardheaded and determined. He reminded them of Sheila.

At the North Carolina reunion, the girls are recalling their favorite experiences with Sheila.

One memory: During high school, Sheila drove this little beat-up yellowish/greenish car. At lunchtime, students were allowed to leave school and get something to eat, as long as they were back before the bell rang. They had exactly thirty-five minutes. So some of the girls would run out to Sheila’s car, and she’d speed them over to Taco Time on the other side of the train tracks that cut through Ames. Lunch at Taco Time could be a great risk because if a long train happened to pass through, and they were stuck waiting behind the gate, they’d be late returning to school.

That’s part of what made it exciting going out for lunch; they were at the mercy of traffic lights, passing trains, the lines at Taco Time, Sheila’s driving. “We’d be laughing so hard, trying to eat lunch as we raced down Lincoln Way,” says Cathy. “It was a race against time, always!”

After talking about the fun times, the conversation turns to the fact that they didn’t stay in touch with the Walshes after Sheila died. “They probably think we forgot about her and went on our way,” says Karen. “They don’t know how much she meant to us.”

“We were twenty-two years old when she died,” says Jenny. “It’s not like we were fully functional adults. We thought we were so young and invincible, and when Sheila died, it was such a shock. We didn’t have the life experiences that we have now, the sense of what’s the right thing to do, how to deal with grief. It would be so different if one of us died now. We’d know how to respond. We’d have more understanding.” Jenny says it’s not an exaggeration to say she thinks of Sheila every day.

Each of the girls has her own specific memory of how she learned about Sheila’s death, and of going (or not going) to the funeral.

Karla, who couldn’t afford to fly in from Arizona, recalls that Jenny was mad at her for not coming. Meanwhile, Kelly and Diana recall driving together to the funeral from the University of Iowa in Iowa City. On the ride, they got into a heavy discussion about heaven and hell. “I didn’t have a strong sense of there being a heaven and Diana did,” says Kelly, “and she was so angry at me. For more than an hour on the road, I don’t think we even spoke.”

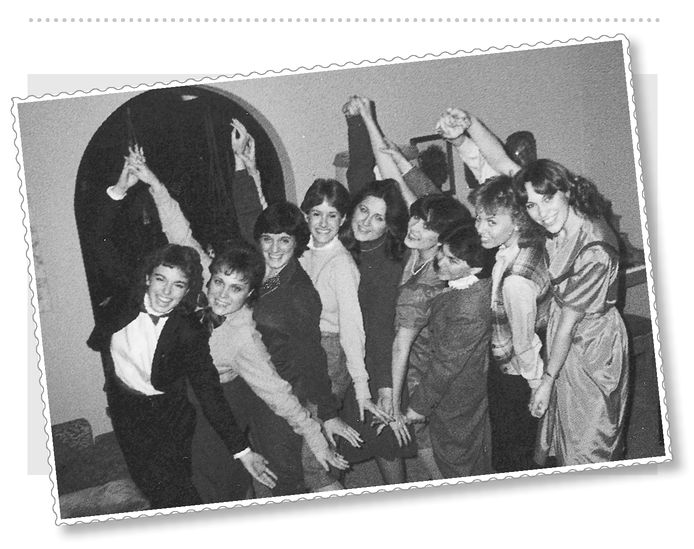

Sheila leads the Ames girls.

Other books

Intentions by Deborah Heiligman

The Blackstone Commentaries by Rob Riggan

The Keepers: Archer by Rae Rivers

A Ransomed Heart by Wolfe, Alex Taylor

Teacher by Mark Edmundson

Anne Barbour by A Talent for Trouble

Home Truths by Freya North

Murder.com by Haughton Murphy

Sea Glass Summer by Dorothy Cannell