The Girls from Ames (27 page)

Read The Girls from Ames Online

Authors: Jeffrey Zaslow

Some of the girls thought Christie’s diary was reminiscent of Anne Frank’s. Day after day, she described a world that had been terribly unfair to her, and yet Christie’s sense of hope and optimism rarely wavered. Of course, unlike the diary of Anne Frank, read well after she had died, Christie’s diary was read in real time by friends and loved ones. She’d post an entry, and minutes or hours later it was being read by her thirteen-year-old friends and by the Ames girls spread across the country.

As she described her friendships in the online diary, the Ames girls were transported back to their earliest days with each other. Some of them checked the Caring Bridge Web site every few hours, waiting for Christie’s latest entry, hoping for good news.

In suburban Philadelphia, Karen felt she was becoming obsessed with Christie’s site. She found herself reading and rereading it ten times a day. She’d come home with groceries, and before she even put them away, she would head for the computer to see if there were any postings from Christie or from other Ames girls giving Christie encouragement.

All the Ames girls thought back to their interactions with Christie over the years. Kelly found herself focused on how inquisitive Christie could be. Once, when Christie was almost two years old, she and Kelly were walking together, and Christie kept looking over her shoulder. She seemed to be very frustrated. “What’s the problem?” Kelly asked. Christie had found her shadow, it turned out, and each time she tried to step away from it, there it was. “It’s stuck to me,” she told Kelly.

Whenever the Ames girls had gotten together, Christie had a habit of sidling up to Karla and eavesdropping on the women—trying to figure out the world of adult friendships, eager to chime in. Karla would shoo her away, sending her off to watch the other kids, which seemed appropriate at the time. But Kelly, for one, was now feeling regretful that they had been so dismissive. Her kids had begun doing the same sort of eavesdropping, and Kelly found herself hesitant to send them away. She wished she could go back in time and welcome Christie into the circle of Ames women.

Now all they could do was read Christie’s diary, feeling helpless as she described her nausea, fevers and vomiting spells. The Ames girls would read the entries, teary-eyed, wondering how much more her little body could take. But Christie had a way of couching bad news with humor. In one entry she wrote: “My faith in ‘everything happening for a reason’ is slowly slipping. Just kidding! But I’m sure ready to be done with puking and pain.” She’d give regular updates about other ill kids at the hospital, asking her readers to keep them in their hearts, too.

In their postings to Christie, the Ames girls’ messages matched their personalities. Jane always found the most positive news and commented on it: “Glad to hear you had a good day, Christie. Your great attitude is so inspiring for all of us, young and old. Continue to stay strong.” Jane could be playful, too: “We loved the new pictures of you with your friends! How many rules did you have to break to get all those lovely friends of yours in your hospital room?”

Cathy, usually reluctant to boast of her celebrity connections, made an exception for Christie: “I’m going to be traveling to London with Pink for ten days. Are you a fan? Would you like some ‘swag’?” Another time, Cathy was working as Courteney Cox’s makeup artist. She knew Christie was a huge

Friends

fan, so she had the show send her mugs, a hat, a T-shirt.

Friends

fan, so she had the show send her mugs, a hat, a T-shirt.

Meanwhile, Kelly took on the persona of the fun aunt, making funky suggestions. “Does your school celebrate homecoming, Christie?” she asked in one posting. “To get you in the fall spirit, your mom should TP your hospital room. Have the nurses catch her in the act and chase her down the halls. ☺” After the East Coast blackout in the summer of 2003, Kelly wrote to Christie: “We had no idea that the cord we tripped over and disconnected from the wall while touring Niagara Falls would trigger the blackout. . . .”

Still, at times, Kelly’s postings had a more reflective tone: “Thanks for being such a wonderful teacher through your Web site, Christie. Many people look forward to your words and we have all learned so much from you.”

Christie often wrote about her feelings for Ben and Jackie, wishing they could have a more normal life, despite the abnormal effect her illness was having on the family. In the middle of everything, Jackie had a far-less-serious medical issue; she needed to have her tonsils taken out. Still, Christie didn’t dismiss it as trivial. She described her kid sister’s recovery and wished her well.

One day, Karla cooked homemade chicken soup for Christie, and Jackie held the container on her lap as they drove it to the hospital. While they were driving, the lid came off and the soup spilled. Jackie ended up with second-degree burns and had to be taken to the hospital’s emergency room. The Ames girls couldn’t imagine how Karla could cope with all of this—having two daughters on opposite ends of the same hospital.

Jane found herself thinking: “We all love our kids. But Karla loves her kids with a capital bold-faced L. She’s so devoted. It seems absolutely cruel for her to be the one going through this.”

The Ames girls pooled money to pay for a cleaning service to clean Karla’s home and to have catered meals sent in. Karla actually was living at the hospital, in Christie’s room. Even though their home was just a few minutes away, Karla didn’t go back to the house for a month or six weeks at a time. She didn’t want to be away from Christie. One night, because her other two children missed her, she went to the house and Bruce spent the night at the hospital. It didn’t feel right.

The Ames girls sent email after email to Karla, letting her know they were thinking about her. Karla rarely responded. When they called, she wouldn’t call back or she’d speak only briefly. “I have to get back to Christie,” she’d say. The girls found it all very frustrating and painful. Kelly thought to herself: “We’re locked out of Karla’s life just when she needs us the most.”

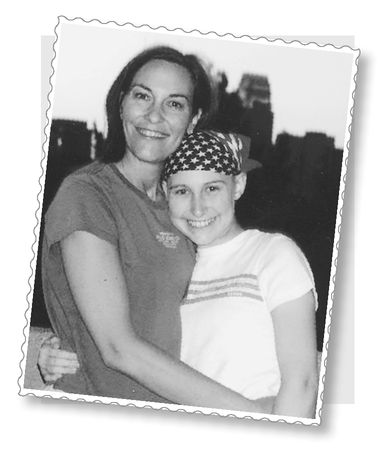

Karla and Christie in Minneapolis

As Karla saw it, she had to cast her friends to the side. On the day Christie was diagnosed, a doctor told Karla that Christie could die. Given that, Karla wanted to be with her daughter every possible minute. The Ames girls would have to understand. For the most part, they did.

For a while, Kelly, living in Minnesota, was visiting the hospital every Wednesday, and reporting back to the other girls. “Karla is in good spirits—very positive and upbeat, which fills the room. Christie looked good and was in good spirits,” she wrote in one email. “She has the power to transform the air around her.”

For Kelly, those Wednesday experiences were life-changing. She saw the loving bonds between Karla and Bruce, and between the couple and their three children. Seeing their strength and closeness, especially given the awful circumstances, made Kelly reconsider her own home life, her own marriage. It was on those Wednesdays that she began to think seriously about the possibility of ending her marriage.

Kelly’s hospital visits had a different effect on Karla, however. Each time Kelly stopped by, her reporter’s instincts kicked in, and she’d have a barrage of questions about Christie’s care or how Karla was holding up. She meant well, but Karla found it annoying. After a while, Karla began to view Kelly’s visits as intrusions, and the questions as “the interrogation.” Once, Kelly came with her entire family, and Karla felt churned up inside. “They’re making small talk,” she thought to herself, “and all I can think about is germs.”

Karla had been sleeping night after night, on a pull-out bed in the hospital room, and Kelly was amazed by her commitment to be by Christie’s side twenty-four hours a day. Kelly later wrote out her impressions: “How can Karla be there every night, with all the sounds, the glowing lights, the smells of that place? I would not be able to do it. God forbid if it was my kid, I would have asked my parents or friends to take a shift.”

On her visits, Kelly sometimes would ask Karla to take a break, to walk with her down the hall to the visitors’ lounge for a few minutes. Invariably, Karla declined to go. “I want to be with Christie,” she said.

When the other Ames girls called Karla and asked if they could visit, Karla turned them down. Visitors were hard on Christie, who was often so weak, and they threatened her immune system. If friends were going to be there, Karla decided, they ought to be Christie’s friends, not Karla’s friends.

Diana came from Arizona to visit, but Karla asked that she just go to the house, not the hospital, and see Bruce, Ben and Jackie. Karla stayed at the hospital. Bruce seemed to be doing OK. He was able to joke around. He said the neighbors had sent over yet another care package dinner of “pity pitas.” It all seemed surreal to Diana, so unlike the easy visits of the past.

K

arla found herself contemplating the fact that she didn’t know the whereabouts of her own biological parents. She couldn’t help but wonder: What insights to Christie’s illness might be revealed in their medical histories? Was the woman named on Karla’s birth certificate the same woman Mrs. Derby had phoned years later? Mrs. Derby had come upon the woman because of the article she wrote about the high prevalence of cancer in her family. The cancer connection was concerning at the time. Now, given Christie’s plight, it was frightening. Would this woman have medical information that could help Christie?

arla found herself contemplating the fact that she didn’t know the whereabouts of her own biological parents. She couldn’t help but wonder: What insights to Christie’s illness might be revealed in their medical histories? Was the woman named on Karla’s birth certificate the same woman Mrs. Derby had phoned years later? Mrs. Derby had come upon the woman because of the article she wrote about the high prevalence of cancer in her family. The cancer connection was concerning at the time. Now, given Christie’s plight, it was frightening. Would this woman have medical information that could help Christie?

Karla was too overwhelmed with Christie’s care to pursue any efforts to find her biological parents. But she thought about them. They had let her out of their lives on that spring day in 1963 with nothing but a cloth diaper. OK, that was the choice they made. But now Christie, their biological granddaughter, was very sick. And Karla felt that her other two children were also entitled to crucial answers about their genetic backgrounds.

Karla didn’t bother Christie with any of these details about the genetic history that may have led her to that hospital room. And in any case, Christie was a realist. She believed in playing the cards she was dealt. Rather than crying over her bad hand, she wondered how she might improve it.

She decided to try cutting-edge treatments. Her antinausea medicine wasn’t working, so her oncologist had her trained in the relaxation technique of guided imagery, where she used her five senses to imagine visiting “a happy place.” Her family had once lived in Seattle, so for her happy place, she chose Seattle’s Pike Place Market. She’d imagine herself at that market, tasting the fruit, smelling the flowers and watching all the fish being thrown around and loaded onto carts. Often, when she used guided imagery, she wouldn’t throw up.

A reporter from

Newsweek

who

,

doing a story on alternative therapies, learned about her from the hospital and interviewed her. She was so excited by the possibility of being quoted in the magazine. In her online journal she continually reminded people to look for the story, but the news cycle kept getting in the way. First, the piece was bumped to make room for coverage of the Washington, D.C., sniper attacks. A week later, Christie wrote, “Don’t go out and buy

Newsweek

. I got bumped again, because of the election.” Finally, the story ran. “Two exciting pieces of news!” Christie wrote. “I’m in this week’s

Newsweek

and I get to go home for Thanksgiving. It doesn’t get any better than this!”

Newsweek

who

,

doing a story on alternative therapies, learned about her from the hospital and interviewed her. She was so excited by the possibility of being quoted in the magazine. In her online journal she continually reminded people to look for the story, but the news cycle kept getting in the way. First, the piece was bumped to make room for coverage of the Washington, D.C., sniper attacks. A week later, Christie wrote, “Don’t go out and buy

Newsweek

. I got bumped again, because of the election.” Finally, the story ran. “Two exciting pieces of news!” Christie wrote. “I’m in this week’s

Newsweek

and I get to go home for Thanksgiving. It doesn’t get any better than this!”

Workers at Pike Place Market in Seattle saw the

Newsweek

story, and a month later, two of them surprised Christie by flying to Minneapolis. They brought gifts for every kid on her floor at the hospital. They had real fish, fruit, T-shirts, flowers, hats. They even brought stuffed fake fish to the hospital playroom, and they threw the fish back and forth, just like they do in Seattle. Christie wrote about the thrill of seeing her “happy place” come to life right there in the hospital.

Newsweek

story, and a month later, two of them surprised Christie by flying to Minneapolis. They brought gifts for every kid on her floor at the hospital. They had real fish, fruit, T-shirts, flowers, hats. They even brought stuffed fake fish to the hospital playroom, and they threw the fish back and forth, just like they do in Seattle. Christie wrote about the thrill of seeing her “happy place” come to life right there in the hospital.

Christie’s journal was also a document of what the early teen years were like, circa 2002/2003. When she was out of the hospital and got to see movies (often wearing a mask to avoid infections), she’d review them in her journal. She found that

Legally Blonde 2

wasn’t as good as the original, “but I still thought it was cute.” She also got a kick out of Jennifer Lopez in

Maid in Manhattan

. (The Ames girls took note, and in a parallel universe where life was still normal, sent their healthy daughters to the same movies.)

Legally Blonde 2

wasn’t as good as the original, “but I still thought it was cute.” She also got a kick out of Jennifer Lopez in

Maid in Manhattan

. (The Ames girls took note, and in a parallel universe where life was still normal, sent their healthy daughters to the same movies.)

Christie’s writing was conversational. She took to calling the hospital “the Ritz,” as in: “My brother, Ben, and mom slept over here last night at the Ritz.” Her sense of humor came through in most every entry. She called the anesthetic she’d taken before surgery “milk of amnesia.” When her hair eventually grew back after chemotherapy, she described what it felt like to use shampoo again and the thrill of walking around with a head that “smells like fresh fruit.”

From the time Christie was in fourth grade, she and Karla had been in a mother/daughter book club with six of Christie’s friends and their moms. The club continued even after she got sick. Christie sometimes felt self-conscious, given her condition and the fact that she needed to wear a mask over her mouth and nose to avoid other people’s germs. She wrote about one book-club meeting: “Of course my mom made me wear my mask.” Then, as usual, Christie turned positive, with a happy face emoticon as punctuation: “I have established quite a talent, through all of this, where I’m able to eat and drink with a mask on!! ☺”

Other books

The Poison Morality by Stacey Kathleen

Curves for the Alpha Wolf by Caroline Knox

[MacKenzie Sally] The Naked Laird(book4me.org) by The Naked Laird

The Iron Queen (Daughters of Zeus) by Bevis, Kaitlin

The Cadet of Tildor by Lidell, Alex

Let it be Me (Blue Raven) by Noble, Kate

Displaced Persons by Ghita Schwarz

How It Feels to Fly by Kathryn Holmes

A Splash of Christmas by Mary Manners