The Gilded Wolves (12 page)

Authors: Roshani Chokshi

S

é

verin’s eyes flashed knowingly to

hers, and Laila forced herself to smile wryly.

“Tristan and Hypnos admired my outfit,” she said, resting her hand on her hip. “No compliment from you?”

“I didn’t have a chance to look,” he said. His smile didn’t meet his eyes. “Too busy avoiding certain death. It’s terribly distracting, you know.”

He could say what he wanted, but she hadn’t forgotten how he’d watched her yesterday. How still

he stood. How his eyes darkened, leaving only a halo of violet. Men had looked at her a thousand ways and times, and none of them had made her feel as she did yesterday. The almost-painful exquisiteness of being unveiled by a glance. It made her feel aware of everything about her—skin stretched over bone, silk clinging to her limbs, her breath heating the air. The kind of awareness that makes one

feel alive.

It terrified her.

It was the same reason why after that one night, she knew it had to end there. There was no point entertaining that awareness when, in less than a year, she wouldn’t even exist. But she still remembered.

She remembered that she’d reached for him first, and he was the first to break it off.

Laila had to leave.

“The driver is waiting for me,” she said.

On her way

out, she gazed over her shoulder at S

é

verin.

“Be sure to appear very sad at L’Eden. After all, if you really were my lover, you should be utterly devastated both by my public dismissal of you and by my marvelous costume.”

She did not wait to see his expression.

Enrique collapsed in his favorite blue armchair in the stargazing room. A thunderstorm rattled the windows, and the curtains covered in embroidered constellations shook like rags of night sky.

“Someone was waiting for us.”

“Revolution man,” said Zofia softly.

He looked up. Zofia was curled warily in the armchair across from him. As usual, she chewed on a matchstick.

“What

did you say?”

“Revolution man,” she said, still not looking at him. “That’s what he talked about. About the start of a new age. Also, the sensor should have picked him up, but it didn’t.”

That had bothered Enrique too. It was almost as if the man had watched them from somewhere, materializing only after they had secured the area for signs of any recording devices or other people. But there was

no way he could have gotten in. The entrance had been locked. The windows were all covered with murals. The exit had been closed and barred until the police officers had broken it open.

All that was in that room were the Forging displays and the massive mirror wall.

Zofia opened her palms, and a golden chain spilled out. A pendant no larger than a franc dangled from it. She brought the chain

to her face, turning over the pendant.

“Where did you get that?”

“He wore it on his neck.”

Enrique frowned. Behind Zofia, the hands of the grandfather clock tilted slowly to midnight. All around them, the stargazing room bore signs of their planning. Papers and blueprints covered every surface. Different sketches of the Horus Eye hung from the ceiling. Until now, this had felt like any other

acquisition: planning, casing, squabbling over cake.

Until the man had raised a knife to him.

It struck him then. The cold knowledge that perhaps someone didn’t want them to find the Horus Eye and would do anything to make sure they didn’t find it. Enrique pulled the artifact from the breast pocket of his jacket. According to his research, it had been placed above the entrance of a Coptic church

in North Africa. Enrique turned over the artifact in his hand. It was made of brass, its edges jagged. When he ran his thumb along the top, he could feel the depressions of grooves, but it was too caked with verdigris to see properly. The back of the square showed chisel marks from where it had been hewn off the base of a statue depicting the Virgin Mary. According to the locals, the square at

the base of the statue emanated a strange glow when someone stepped into the church carrying evil in their hearts. He’d never heard of a stone Forged to do such a thing except verit. If this square held a piece—or pieces, though that seemed impossible—of verit, then perhaps it had detected a weapon on a man who had entered the church. Perhaps the man truly was bad, and when they’d noticed the glowing

stone, they’d accosted him,

found the weapon, and made their own connections. There was always an observation at the root of a superstition.

“It’s a honeybee,” said Zofia suddenly.

“What?”

She held up the chain pendant. “It’s in the shape of a honeybee.”

“A strange fashion choice,” said Enrique, distracted. “Or a symbol, perhaps? Maybe he sympathized with Napoleon? I’m fairly certain honeybees

were thought to be a symbol of his rule.”

“Did Napoleon like mathematicians?”

“What does that have to do with anything?”

“Honeybees make perfect hexagonal prisms. My father called them nature’s mathematicians.”

“Maybe?” said Enrique. “But seeing as how Napoleon died in 1821, I don’t think I’ll have the opportunity to ask him.”

Zofia blinked at him, and a pang of guilt struck Enrique. She

couldn’t always process jokes the way the others did, and sometimes his attempts at wit came off severe rather than sophisticated. But Zofia didn’t notice. Shrugging, she placed the honeybee chain on the coffee table between them.

Enrique turned the artifact over in his hands. “Where did he come from, though? Was he waiting the whole time, or was there a door there?”

“No doors except the entrance

and exit we noted.”

“I just don’t understand what he wanted. Why wait for us? Who was he?”

Zofia glanced at the honeybee necklace and made a noncommittal

hrmm

sound and then stuck out her hand. “Hand me that.”

“Have you never heard the saying ‘you attract more flies with honey than vinegar’?”

“Why would I want to attract flies?”

“Never mind.”

Enrique handed it to her. “Be careful,” he said.

“It’s nothing but brass with some corrosion,” she said disdainfully.

“Can you take off the corrosion?”

“Easily,” she said. She rattled the square. “I thought you said this could be solid verit inside? This looks like the superstitious charms sold in my village. What proof did you have? What was your research?”

“Superstition. Stories,” said Enrique, before adding just to annoy her: “A gut instinct.”

Zofia made a face. “Superstitions are useless. And a gut cannot have an instinct.”

She took a solution from her makeshift worktable and cleaned off the square. When she was finished, she slid it across the table. Now, he could make out a gridlike pattern and the shape of letters, but little else. In the stargazing room, the fires had been banked. No lanterns were allowed so as not to disrupt

the view of the stars, and only a couple of candle tapers stood on the table.

“I can barely see,” said Enrique. “Do you have flint to light the match?”

“No.”

Enrique sighed, looking around the room. “Well, then I—”

He stopped when he heard the unmistakable sound of fire ripping from a match. Zofia held a tiny fire out in her hand. In her other hand, she took a second match and struck it against

the bottom of one of her canine teeth. Firelight lit up her face. Her platinum hair looked like the haze of lightning on the underside of a cloud. That glow looked natural on her. As if this was the way she was meant to be seen.

“You just struck a match with your teeth,” he said.

She looked at him quizzically. “I’ll have to do it again if you don’t light the candles before these burn out.”

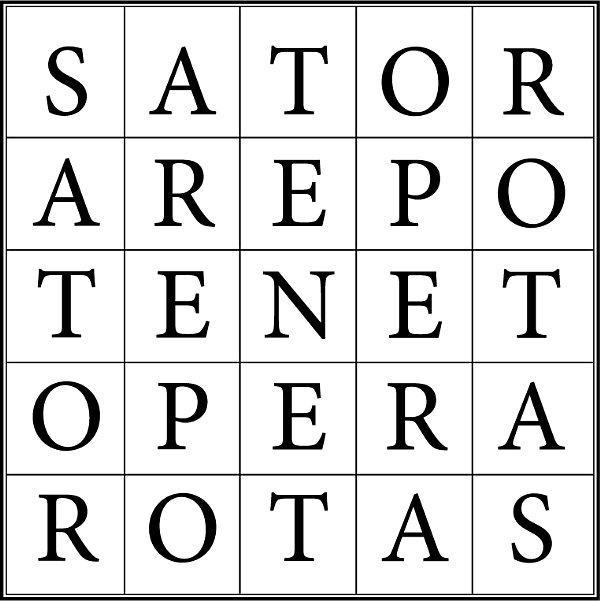

He quickly lit the candles. Then he took one and held it over the metal disc that had slipped out of the compass, examining it. On closer inspection, he saw writing on its surface. All the letters on the square were concentrated in the middle, but there were enough squares for twenty-five letters to be written vertically and horizontally.

His heart began to race. It always did whenever he felt on the verge of discovering something.

“Looks like Latin,” said Enrique, tilting the disc. “

Sator

could mean ‘founder,’ usually of a divine nature?

Arepo

is perhaps a proper name, though it doesn’t seem Roman. Maybe Egyptian.

Tenet

means to hold or preserve … then there’s

opera

, like work, and then

rotas

, plural for ‘wheels.’”

“Latin?”

asked Zofia. “I thought this artifact was from a Coptic church in North Africa.”

“It is,” said Enrique. “North Africa was one of the first places Christianity spread, believed to be as early as the first century … and Rome had frequent interaction with North Africa. I believe their first colony is now known as Tunisia.”

Zofia took one of the other candles and held it close to the disc.

“If

the verit is inside, can I just break it?”

Enrique snatched the brass square off the table and clutched it. “

No.

”

“Why not?”

“I am

tired

of people breaking things before I get a chance to see them,” he said. “And besides, look at this switch on the side.” He pointed to a small toggle sunken into the width of the square. “Some ancient artifacts have failsafes to protect the object within, so

if you smash it, you might destroy whatever is inside it.”

Zofia slouched, nesting her chin in her palm. “Perhaps one day I’ll discover how to chisel verit stone itself.”

Enrique whistled. “You’d be the most dangerous woman in France.”

As a rule, it was impossible to break verit stone. Every piece that existed at the entrance of palaces, banks, and other wealthy institutions were raw slabs

that had naturally come apart during the lengthy mining and purification process. All of which made procuring a gravel-sized piece of verit unheard of, even on the extensive black market that usually suited their purposes.

“The words are the same,” said Zofia.

“What do you mean?”

“They’re just the same. Can’t you see it?”

Enrique stared at the letters, and then realized what she meant. There

was an

S

in the upper left and bottom right corner. An

A

adjacent to both. From there, the pattern made sense.

“It’s a palindrome.”

“It’s a metal square with letters.”

“Yes, but the letters spell the same thing backward and forward,” said Enrique. “Palindromes used to be inscribed on amulets to protect the wearer from harm. Not just amulets, though, come to think of it. There was one in ancient

Greek found outside the Ha

gia Sophia church in Constantinople.

Nipson anom

ē

mata m

ē

monan opsin.

‘Wash the sins, not only the face.’ It was thought the wordplay would confuse demons.”

“Wordplay confuses me too.”

“I shall withhold comment,” said Enrique. He studied the letters once more. “There’s something familiar about this arrangement … I feel as though I’ve seen it before.”

Enrique walked

over to the library within the stargazing room. He was looking for a specific tome, something he had come across during his linguistic studies in ancient Latin—

“Found you,” he said, pulling out a small volume:

EXCURSIONS TO THE LOST CITY OF POMPEII

.

He quickly scanned the pages before he found what he was looking for.

“I knew it! This arrangement is called the Sator Square,” he said. “It was

found in the ruins of Pompeii in the 1740s, commissioned by the king of Naples. Apparently, the Order of Babel helped fund the excavation alongside Spanish engineer Roque Joaqu

í

n de Alcubierre in hopes that it would reveal previously unknown Forge instruments.”

“Did it?”

“Doesn’t look like it,” said Enrique.

“What about the palindrome’s meaning?”

“Still under scrutiny,” he said. “Nothing else

has appeared like it in the ancient realm, so it’s either a riddle or a cryptogram or a very bored inscription by someone who was about to be killed by a gigantic volcano. Personally, I think it’s a key … Figure out the code and the brass square will unlock. Maybe there’s some math involved here … Zofia? Any ideas?”

Zofia chewed on the end of a matchstick. “There’s no math to it. Just letters.”

Enrique paused. An idea flying to his head.

“But numbers and letters have plenty in common…” he said slowly. “Mathematics and the Torah led to gematria, a Kabbalistic method of interpreting Hebrew scripture by assigning numerical value to the words.”

Zofia sat upright. “My grandfather used to give us riddles like that. How do you know about that?”

“It’s been around for some time,” said Enrique,

feeling his academic tone creeping into his voice. He had a bizarre urge to sit in a leather chair and acquire a fluffy cat. And a pipe. “Mathematics has long been considered the language of the divine. Besides, the system of alphanumeric codes doesn’t just belong to the Hebrew language. Arabs did it with

abjad

numerals.”

“Our

zeyde

taught my sister and I how to write coded letters to each other,”

said Zofia softly. She twirled a strand of platinum hair around her finger. “Every number matched its alphanumeric position on the alphabet. It was … fun.”

At this, the barest smile touched her face. Not once had he ever heard her talk about her family. But no sooner had she mentioned them than she set her jaw. Before he could say anything, Zofia grabbed a quill and scraps of paper.

“If I take

all these letters from your Sator Square, and look at their position in the alphabet and add them up, here’s what we get.”

S A T O R

⇒

S

+

A

+

T

+

O

+

R

=

19

+

1

+

20

+

15

+

18

=

73A R E P O

⇒

A

+

R

+

E

+

P

+

O

=

1

+

18

+

5

+

16

+

15

=

55T E N E T

⇒

T

+

E

+

N

+

E

+

T

=

20

+

5

+

14

+

5

+

20

=

64O P E R A

⇒

O

+

P

+

E

+

R

+

A

=

15

+

16

+

5

+

18

+

1

=

55R O T A S

⇒

R

+

O

+

T

+

A

+

S

=

18

+

15

+

20

+

1

+

19

=

73