The Gilded Wolves (4 page)

Authors: Roshani Chokshi

“Break it,” said S

é

verin.

“

What?

” Enrique clutched the object to his chest. “The compass is thousands of years old! There’s another way to pry it,

gently

, apart—”

S

é

verin lunged. Enrique tried to snatch it away, but he wasn’t as fast. In one swift motion, S

é

verin grabbed both sides of the compass. Enrique heard it before

he saw it. A brief, merciless—

Snap

.

Something dropped from the compass, thudding on the hansom’s floor. S

é

verin got to it first, and the minute he held it up to the light, Enrique felt as if a cold hand had pushed down on his lungs and squeezed the breath out of him. The object hidden within the compass certainly looked like a map. All that was left was one question: Where did it lead?

Zofia liked Paris best in the evening.

During the day, Paris was too much. It was all noise and smell, crammed with stained streets and threaded with hectic crowds. Dusk tamed the city. Made it manageable.

As she walked back to L’Eden, Zofia clutched her sister’s newest letter tight to her chest. Hela would find Paris beautiful. She would like the linden trees of rue Bonaparte.

There were fourteen of them. She would find the horse chestnuts comely. There were nine. She would not like the smells. There were too many to count.

Right now, Paris did not seem beautiful. Horse shit marred the cobbled roads. People urinated on the street lanterns. And yet, there was something about the city that spoke vibrantly of life. Nothing felt still. Even the stone gargoyles leaned off

the edges of buildings as if they were on the verge of flight. And nothing looked lonely. Terraces had the company of wicker chairs, and bright purple bougainvillea hugged stone walls. Not even the Seine River, which cut through Paris like a trail of ink, looked abandoned. By

day, boats zipped across it. By night, lamplight danced upon the surface.

Zofia peeked at Hela’s newest letter, sneaking

lines beneath every shining lantern. She read one sentence, then found that she could not stop. Every word brought back the sound of Hela’s voice.

Zosia, please tell me you are going to the Exposition Universelle! If you do not, I will know. Trust me, dear sister, the laboratory can spare you for a day. Learn something outside the classroom for once. Besides, I heard the world fair will have

a cursed diamond, and princes from exotic lands! Perhaps you might bring one home, then I will not have to play governess to our stingy

stryk

. How he can be father’s brother is a mystery for only God to ponder

.

Please go

.

You are sending back so much money lately that I worry you are not keeping enough for yourself. Are you hale and happy? Write to me soon, little light.

Hela was half-wrong.

Zofia was not in school. But she was learning plenty outside of a classroom. In the past year and a half, she had learned how to invent things the

É

cole des Beaux-Arts never imagined for her. She had learned how to open a savings account, which might—assuming the map S

é

verin acquired was all they’d hoped it to be—soon hold enough money to support Hela through medical school when she finally enrolled.

But the worst lesson was learning how to lie to her sister. The first time she had lied in a letter, she’d thrown up. Guilt left her sobbing for hours until Laila had found and comforted her. She didn’t know how Laila knew what bothered her. She just did. And Zofia, who never quite grasped how to find her way through a conversation, simply felt grateful someone could do the work for her.

Zofia

was still thinking about Hela when the marble entrance of the

É

cole des Beaux-Arts manifested before her. Zofia staggered back, nearly dropping the letters.

The marble entrance did not move.

Not only was the entrance Forged to appear before any matriculated students two blocks from the school, but it was also an exquisite example of solid matter and mind affinity working in tandem. A feat only

those trained at the

É

cole could perform.

Once, Zofia would have trained with them too.

“You don’t want me,” she said softly.

Tears stung her eyes. When she blinked, she saw the path to her expulsion. One year into schooling, her classmates had changed. Once, her skill awed them. Now, it offended them. Then the rumors started. No one seemed to care at first that she was Jewish. But that changed.

Rumors sprang up that Jews could steal anything.

Even someone else’s Forging affinity.

It was completely false, and so she ignored it. She should have been more careful, but that was the problem with happiness. It blinds.

For a while, Zofia was happy. And then, one afternoon, the other students’ whispers got the better of her. That day, she broke down in the laboratory. There were too many

sounds. Too much laughing. Too much brightness escaping through the curtain. She’d forgotten her parents’ lesson to count backward until she felt calm. Whispers grew from that episode.

Crazy Jew.

A month later, ten students locked themselves in the lab with her. Again came the sounds, smells, laughing. The other students didn’t grab her. They knew the barest touch—like a feather trailed down skin—hurt

her more. Calm slipped out of reach no matter how many times she counted backward, or begged to be let go, or asked what she had done wrong.

In the end, it was such a small movement.

Someone had kicked her to the ground. Another person’s elbow clashed into a vial on a table. The vial splattered into a puddle, which pooled out and touched the tips of her outstretched fingers. She had been holding

a piece of flint in her hand when fury flickered in her

mind.

Fire

. That little thought—that snippet of will, just as the professors had taught her—traveled from her fingertips to the puddle, igniting the broken vial until it bloomed into a towering inferno.

Seven students were injured in the explosion.

For her crime, she was arrested on grounds of arson and insanity, and taken to prison. She

would have died there if not for S

é

verin. S

é

verin found her, freed her, and did the unthinkable: He gave her a job. A way to earn back what she’d lost. A way out.

Zofia rubbed her finger across the oath tattoo on her right knuckle. Luckily, it was only temporary or her mother would have been appalled. She could not be buried in a Jewish cemetery with a tattoo. The tattoo was a contract between

her and S

é

verin, the ink Forged so that if one of them broke the agreement, nightmares would plague them. That S

é

verin had used this tattoo—a sign of equals—instead of some of the cruder contracts was something she would never forget.

Zofia turned on her heel and left rue Bonaparte behind. Perhaps the marble entrance could not recognize when a student had been expelled, for it did not move, but

stayed in its place until she disappeared around a corner.

IN L’EDEN, ZOFIA

made her way to the stargazing room. S

é

verin had called for a meeting once he and Enrique got back from their latest acquisition, which she knew was just a fancy word for “theft.”

Zofia never took the grand lobby’s main staircase. She didn’t want to see all the fancy people dressed up and laughing and dancing. Plus,

it was too noisy. Instead, she took the servants’ entryway, which was how she ran into S

é

verin. He grinned despite appearing thoroughly disheveled. Zofia noticed how tenderly he held his wrist.

“You’re covered in blood.”

S

é

verin glanced down at his clothes. “Surprisingly, it hasn’t escaped my attention.”

“Are you dying?”

“No more than usual or expected.”

Zofia frowned.

“I’m well enough.

Don’t worry.”

She reached for the door handle. “I’m glad you’re not dead.”

“Thank you, Zofia,” said S

é

verin with a small smile. “I will join you soon. There’s something I’d like to show everyone through a mnemo bug.”

On S

é

verin’s shoulder, a Forged silver beetle scuttled under his lapel. Mnemo bugs recorded images and sound, allowing projection-like holograms should the wearer choose. Which

meant she had to be prepared for an unexpected burst of light. S

é

verin knew she didn’t like those. They jolted her thoughts. Nodding, Zofia left him in the hall and walked into the room.

The stargazing room calmed Zofia. It was wide and spacious, with a glass-domed vault that let in the starlight. All along the walls were orreries and telescopes, cabinets full of polished crystal, and shelves

lined with fading books and manuscripts. In the middle of the room was the low coffee table that bore the scuff marks and dents of a hundred schemes that came to life on its wooden surface. A semicircle of chairs surrounded it. Zofia made her way to her seat. It was a tall metal stool with a ragged pillowcase. Zofia preferred to balance upright because she didn’t like things touching her back. In

a green, velvet chaise across from her sprawled Laila, who absentmindedly traced the rim of her teacup with one finger. In a plushy armchair crowded with pillows sat Enrique, who had a large book on his lap and was reading intently. Of the two chairs left, one was Tristan’s—which was less of a chair and more of a cushion because he didn’t like heights—and one was S

é

verin’s, a black-cherry armchair

Zofia had custom-Forged so that an unfamiliar touch caused it to sprout blades.

Tristan barged into the room, his hands outstretched.

“Look! I thought Goliath was dying, but he’s fine. He just molted!”

Enrique screamed. Laila scuttled backward on her chaise. Zofia leaned forward, inspecting the enormous tarantula in Tristan’s hands. Mathematicians didn’t frighten her, and spiders—and bees—were

just that. A spider’s web was composed of numerous radii, a logarithmic spiral, and the light-diffusing properties of their webs and silk were fascinating.

“Tristan!” scolded Laila. “What did I just tell you about spiders?”

Tristan lifted his chin. “You said not to bring him into your room. This is not your room.”

Faced with Laila’s glare, he shrank a bit.

“Please can he stay for the meeting?

Goliath is different. He’s special.”

Enrique pulled his knees up to his chest and shuddered. “What is so special about

that

?”

“Well,” said Zofia, “as part of the infraorder of Mygalomorphae, the fangs of a tarantula point

down

, whereas the spiders you’re thinking of have fangs which point and join in a pincerlike arrangement. That’s rather special.”

Enrique gagged.

Tristan beamed at her. “You

remembered.”

Zofia did not find this particularly noteworthy. She remembered most things people told her. Besides, Tristan had listened just as attentively when she explained the arithmetic spiral properties of a spiderweb.

Enrique made a

shoo

motion with his hands. “Please take it away, Tristan. I beg you.”

“Aren’t you happy for Goliath? He’s been sick for days.”

“Can we be happy for Goliath

from behind a sheet of glass and a net and a fence? Maybe a ring of fire for good measure?” asked Enrique.

Tristan made a face at Laila. Zofia knew that pattern: widened eyes, pressed-down brows, dimpled chin, and the barest quiver of his bottom lip. Ridiculous, yet effective. Zofia approved. Across from her, Laila clapped her hands over her eyes.

“Not falling for it,” said Laila sternly. “Go

look like a kicked puppy elsewhere. Goliath can’t stay here during a meeting. That’s final.”

Tristan huffed. “

Fine

.” Then he murmured to Goliath, “I’ll make you a cricket cake, dear friend. Don’t fret.”

Once Tristan had left, Enrique turned to Zofia. “I rather sympathized with Arachne after her duel with Minerva, but I detest her descendants.”

Zofia went still. People and conversation were

already a cipher without throwing in all the extra words. Enrique was especially confusing. Elegance illuminated every word the historian spoke. And she could never tell when he was angry. His mouth was always bent in a half smile, regardless of his mood. If she answered now, she’d only sound foolish. Instead, Zofia said nothing, but pulled out a matchbox from her pocket and turned it over in her

hands. Enrique rolled his eyes and turned back to his book. She knew what he thought of her. She had overheard him once.

She’s a snob

.

He could think what he liked.

As the minutes ticked by, Laila handed out tea and desserts, making sure Zofia received exactly three sugar cookies, all pale and perfectly round. She settled back in her chair, glancing around the room. Eventually, Tristan returned

and dramatically plopped onto his cushion.

“In case you’re wondering, Goliath is deeply offended, and he says—”

But they would never know the tarantula’s specific grievances because at that moment a beam of light shot up through the coffee table. The room went dark. Then, slowly, an image of a piece of metal appeared. When she looked up, S

é

verin was standing behind Tristan. She hadn’t heard

him enter.

Tristan followed her gaze and nearly jumped when he saw S

é

verin. “Must you creep up on us like that? I didn’t even hear you come into the room!”

“It’s part of my aesthetic,” said S

é

verin, dangling a Forged muffling bell.

Enrique laughed. Laila didn’t. Her gaze was fixed on his bloodied arm. Her shoulders dropped a bit, as if she was relieved it was only his arm that was bloodied.

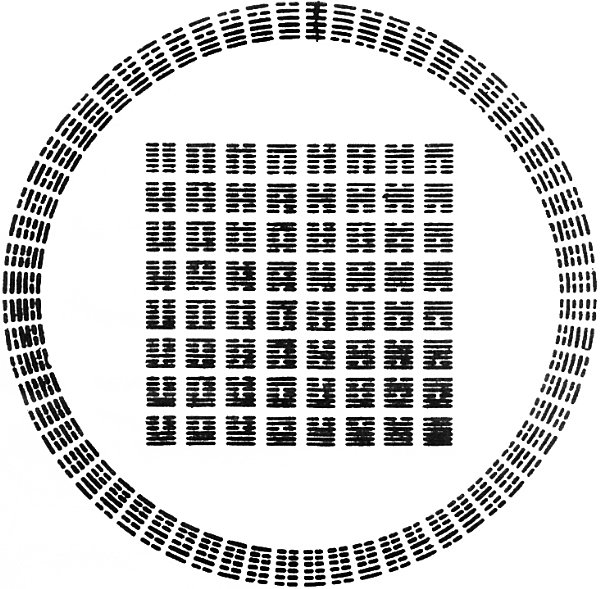

Zofia knew he was alive and well enough, so she turned her attention to the object. It was a square piece of metal, with curling symbols at the four corners. A large circle had been inscribed upon the middle. Within the circle were small rows of stacked lines shaped like squares: