The Giants and the Joneses (10 page)

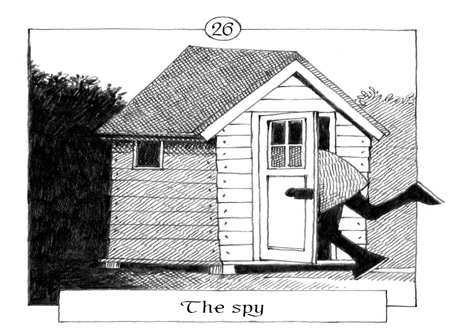

The spy

C

OMINGS AND GOINGS

. Goings and comings. Throg had been keeping a watchful eye on the policeman’s house, and it was all very suspicious.

First the boy had gone away. A day or so later the old lady had arrived and the mother had gone away. And then, yesterday evening, the boy had come back again, accompanied by an old man. What did it all mean? Throg felt sure that in some mysterious way this family was in league with the iggly plops. Most likely

the whole police force was involved too.

Throg crept up to the front door. He could hear raised voices inside the house. One of them seemed to be crying and shrieking. Throg’s hearing wasn’t as good as his eyesight, but he was convinced he heard the words ‘iggly plop’.

He knocked at the door. He knew that if he asked the usual question he would get the usual answer, so he decided he would try and catch them out. Instead of asking if they had seen any iggly plops he would ask them

how many

they had seen.

The policeman opened the door. Throg recognised him even though he wasn’t wearing his uniform.

‘Heek munchly iggly plops?’ he asked.

The man seemed to hesitate – a sure sign of guilt. Then, as he opened his mouth to speak, the girl charged out of a room. Her face looked swollen and tear-stained, and in her hand she carried a string of knotted handkerchiefs.

‘Nug!’ she shouted. ‘Nug iggly plops! Glay awook!’

The father put an arm round the girl, but she wriggled it off and ran upstairs. The man shrugged

apologetically. ‘Yimp,’ he said to Throg, and closed the door.

Throg hovered on the pavement, uncertain what to do, and then a picture flashed into his mind. It was a picture of the back garden, on the day that he had spoken to the old lady. He could see the scene quite clearly: he was leaning over the garden gate, and the old lady had left her knitting on a chair to come and talk to him. The girl was there too, and a black spratchkin which had jumped out of her arms and run to the garden shed. All the time that Throg and the old lady had been talking, the spratchkin had been poking about under the shed. That must be where the iggly plops were hiding!

Clutching his can of weedkiller, Throg hobbled down the lane at the side of the house. He opened the gate and crept into the back garden. There was the shed – and there, on his knees, reaching under it with a stick, was the boy.

Hearing Throg’s feet crunching on the gravel, the boy turned round. He was grinning.

Throg came straight out with his new question:

‘Heek munchly iggly plops?’ and this time he got a different answer.

‘Thrink,’ said the boy, holding out three fingers as if Throg was an idiot. Then a cunning look came into his face, and he asked if there was a reward for finding them and handing them over.

Of course there was a reward! ‘Sprubbin!’ Throg told him. The reward for giving up the iggly plops would be joy – the joy of having freed Groil from the wicked creatures who were planning to destroy it.

But the boy didn’t seem interested in that kind of reward. He had lost interest in poking around under the shed too; dropping his stick, he made a rude sign at Throg and went into the house.

Never mind. Throg knew where they were now, and he was certain there were more than three of them. There was probably a whole army under there.

He unscrewed the top of his can, in readiness; then he lowered his old body to the ground. Lying on his tummy, he peered under the shed.

Nothing. Nothing except a few cobwebs and a couple of blackberries. They had got away, the rascals! Or they had been hidden away.

As Throg heaved himself back to his feet, he heard someone opening the back door of the house. At the same time, he noticed that the shed door was open a crack. Before he could be spotted he slipped inside.

Peeping through the crack, he saw the girl come out of the house. He noticed that she was carrying a small wooden box. Halfway down the garden path she paused and looked over her shoulder, as if she was afraid someone might be following her.

And someone soon would be following her! Throg was just about to creep out of the shed and go after her himself when he heard more footsteps on the path.

It was the boy again. Like the girl, he had a secretive air about him. When he reached the garden gate he stopped, peered over it and then waited for a few minutes before opening it.

Was he stalking his sister, spying on her? Or was it just a game?

If so, it was a game which Throg could play too.

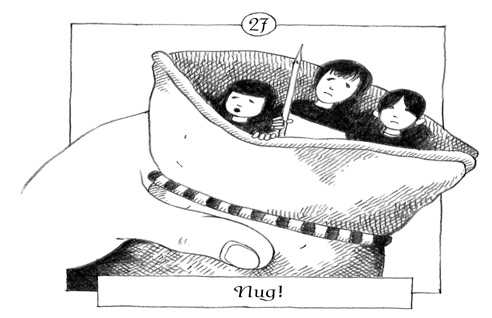

Nug!

T

EARS BLINDED

J

UMBEELIA’S

eyes as she ran along the road towards the edgeland. Her feet tapped out an angry rhythm:

Zab ez frikely, Zab ez frikely.

Why couldn’t her horrible brother have stayed with Grishpij for ever instead of coming back home and messing up her life again? What had he done with the iggliest plop?

Jumbeelia didn’t believe for a moment that the tiny girl had knotted those handkerchiefs together all by

herself. And she couldn’t possibly have opened the cage door from inside. The whole thing was Zab’s doing. She remembered how he loved setting tests and trials for the other two iggly plops. This sheet-ladder must be another of those. Zab denied it, of course, but even Pij and Grishmij didn’t believe him.

Had Zab let the iggly plop escape? Worse, could he have handed her over to that mad old Throg?

The most likely thing was that he was hiding her somewhere, to tease Jumbeelia, and in the hope of doing yet another sweefswoof. But she had already swapped him the iggly strimpchogger and the iggly pobo, and she knew he wasn’t interested in the iggly frangle because it didn’t work. There were no other iggly gadgets left in Jumbeelia’s collection. Her only hope was to climb down the bimplestonk again in search of some items which might appeal to Zab.

That is, if the bimplestonk was still there. She had heard old Throg chanting about how he had kraggled it. Just in case he really had, Jumbeelia had brought the box of bimples. They rattled gently in time to her footsteps:

Zab ez frikely, Zab ez frikely, Zab ez …

Crash! The rhythm stopped abruptly as Jumbeelia stumbled over something and fell.

She had grazed her knee slightly, but far more interesting than the droplets of blood was the object which had tripped her up. It was the iggly strimpchogger.

So Zab had been here! What was he doing so near the edgeland? Could he have taken the iggly plop there?

A new and horrible fear filled Jumbeelia’s mind as she picked up the strimpchogger and continued on her way.

She clambered over the wall into the edgeland. The mist swirled around her as she inched her way forward over the slippery rocks towards the emptiness.

A reddish boulder loomed out of the mist. She noticed that there were some words scratched on the stone in uneven capital letters:

ISH EZ QUEESH THROG KRAGGLED O BIMPLESTONK.

So old Throg had carved these ragged letters. And perhaps he really had killed the bimplestonk too, as the

writing boasted, because here she was at the very edge of the land, and there was no sign of it.

Jumbeelia peered out into the emptiness, and reached out too. Nothing. No stalk, no leaves, no pods full of bimples.

And then she saw it. Not the bimplestonk, but the glove – an old gardening glove, lying at the foot of the boulder.

Jumbeelia picked the glove up, and then nearly dropped it in shock when it spoke to her.

‘Put us down!’ it said.

Jumbeelia peeped into the glove and there, peeping back at her from one of the fingers, was the boy iggly plop. He was waving a nail and looking fierce.

Jumbeelia saw that the other two were there as well, tucked inside two more fingers. How

could

Zab have just left them there like that?

Never mind – they were safe now. She spoke to them reassuringly, telling them that she would take them back home, get Pij to build them a newer, bigger, cage, and that she wouldn’t let Zab or the spratchkin get them, not ever again. She would put them in her collecting bag now and take them straight back home …

‘Nug!’ a voice interrupted her.

It wasn’t the boy this time. It wasn’t the wild girl either. It was the iggliest one, and it was speaking to her in Groilish!

‘Nug, Jumbeelia. Glay jum, boff bimplestonk.’

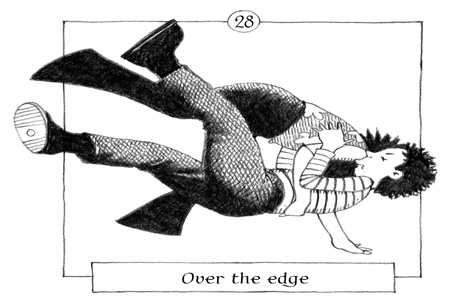

Over the edge

‘G

LAY JUM, BOFF

bimplestonk,’ repeated Poppy.

Colette could hardly believe what she was hearing. Her little sister, who couldn’t even speak English properly, was talking away to a giant. And Jumbeelia was answering her. They were having a proper conversation.

When Colette thought back, it began to make sense. Poppy had spent nearly a week on her own with Jumbeelia. And more recently, in the cage, she had been

chatted to every day in giant language – not just by Jumbeelia but by her father and grandmother.

Although Colette couldn’t understand the words, she could read the expressions on Jumbeelia’s face. The girl giant looked puzzled at first, and then a little disappointed.

‘What was all that gobbledygook?’ Stephen asked.

‘I saying go home down beanstalk,’ said Poppy.

‘What beanstalk?’ Stephen sounded like his old irritable self, but Poppy wasn’t put out. ‘Big girl got beans,’ she said.

Jumbeelia started spouting some more giant language. Colette didn’t think she sounded happy at all.

‘What’s she saying now?’

‘Big girl saying she likes us. She’s got nice house.’

‘Tell her we want to see our mum and dad again.’

‘Oggle woor mij tweeko, oggle woor pij tweeko,’ Poppy pleaded with Jumbeelia.

Jumbeelia seemed to understand at last. Her face cleared, and she lowered the glove gently down to the ground.

The three children scrambled out. Jumbeelia

squatted beside them, and Colette saw that she was holding a box, made of different shapes of painted wood. She was fiddling about with it, as if she was searching for something on its surface, a hidden lever or panel. Suddenly a drawer in the box sprang open. She lowered it so they could all see the squirly wrinkled round things inside.

‘Bimples,’ she said.

‘Big girl saying beans,’ said Poppy.

‘Obviously,’ said Stephen, but he couldn’t guess Jumbeelia’s meaning when she then announced, ‘Bimplestonk chingulay.’

‘Beanstalk tomorrow,’ Poppy translated proudly.

‘She’s going to throw one of them over the edge,’ said Colette. ‘That must be how the last beanstalk sprang up.’

A warm feeling of relief spread through her whole body. Bean today, beanstalk tomorrow. Just one more day! That wasn’t long to wait. And now Jumbeelia was on their side!

She looked up gratefully and saw that Jumbeelia was smiling down at her. Suddenly the girl giant felt like a real friend.

Jumbeelia reached into the box to pick up a bean.

At the same time, a figure emerged from the mist and they heard a voice.

‘Wahoy!’

Colette’s relief chilled into terror. It was Zab.

‘Quick! Hide!’ yelled Stephen. He took Poppy’s hand and pulled her behind the carved boulder. Colette ran after them, but she was too late. Zab had spotted her. She heard his leering laugh, and the next moment his fingers were curled around her body, squeezing her and lifting her up in the air.

And now he was stretching his arm, reaching out into the cold mist beyond the edge of the land.

He wouldn’t really do it, surely? He wouldn’t throw her off? He was just trying to wind up his sister, wasn’t he? Colette’s heart beat furiously.

‘Wunk, twunk, thrink …’

She felt his grip loosen.

‘Askorp!’ came Jumbeelia’s voice suddenly.

The grip tightened again. Colette saw that the girl giant was standing beside her brother, and that she too was dangling something over the edge of Giant Land.

It was the lawn mower!

‘Nug! Osh ez

mub

strimpchogger,’ cried Zab.

‘Osh ez

mub

iggly plop,’ replied Jumbeelia, and Colette realised that Zab was being forced to choose between her life and the loss of the lawn mower.

Zab hesitated. Slowly, he lowered Colette – then stuffed her into his trouser pocket while he lunged for the lawn mower. Colette peered out fearfully and saw him try to wrest it from Jumbeelia’s grasp.

They were struggling now, locked together in serious combat. Colette lost her grip on the edge of the pocket and slipped down inside it.

In the crushing darkness she was swung this way and that, till there came an enormous jolt, and she heard Stephen shout, ‘Quick, Colette! Climb out! They’re on the ground.’

Colette managed to wriggle her way out of the pocket into the pale chilly daylight. She slid down Zab’s thigh on to the rocky ground.

Stephen was there, waiting. He caught her hand and tugged her behind the rock. There was Poppy, and the sheep, who was eating their supply of

parsley, completely unaware of the crisis.

The children peered round the boulder and saw the two giants wrestling. They saw Zab tug the lawn mower free from Jumbeelia’s hands. They saw him break away from her with a jerk which sent her rolling in the other direction.

And they saw her slip over the edge.

‘No! Nug! Help big girl! Aheesh!’ cried out Poppy. She ran forward.

‘Come back, Poppy!’

All of them froze, aghast at the sight of Jumbeelia, who was clinging to a ridge of rock with the fingers of both hands. Her body was dangling over the edge of the land.

Zab looked aghast too. He was kneeling beside her, clutching one arm and trying to pull her back to safety. But he wasn’t strong enough. Now Jumbeelia had lost her hold on the rock, and was dangling in Zab’s grip.

‘If he doesn’t let go she’ll pull him over too,’ said Stephen.

‘Aheesh! Aheesh!’ shouted Zab at the top of his voice.

‘Ee aheesh! I help!’ cried Poppy, but Stephen held her back, and Colette said gently, ‘We can’t help. We’re too small.’

‘No one can help them now,’ said Stephen.