The Ghost in the Machine (26 page)

evolution of our own species. It is now generally recognised that the

human adult resembles more the embryo of an ape than an adult ape. In

both simian embryo and human adult, the ratio of the weight of the brain

to total body weight is disproportionately high. In both, the closing

of the sutures between the bones of the skull is retarded to permit

the brain to expand. The back-to-front axis through man's head -- i.e.,

the direction of his line of sight -- is at right angles to his spinal

column: a condition which, in apes and other mammals, is found only in the

embryonic, not in the adult stage. The same applies to the angle between

backbone and uro-genital canal -- which accounts for the singularity of

the human way of copulating face to face. Other embryonic -- or, to use

Bolk's term,

foetalised

-- features in adult man are: the absence of

brow-ridges; the scantness and late appearance of body hair; pallor of

the skin; retarded growth of the teeth, and a number of other features --

including 'the rosy lips of man which were probably evolved in the young

as an adaptation to prolonged suckling and have persisted in the adult,

possibly under the influence of sexual selection' (de Beer). [6]

wrote J.B.S. Haldane, 'it will probably involve still greater prolongation

of childhood and retardation of maturity. Some of the characters

distinguishing adult man will be lost.' [7] There is, incidentally, a

reverse of the medal which Aldous Huxley pointed out in one of his later,

despairing novels: artificial prolongation of the absolute lifespan of

man might provide an opportunity for features of the adult primate to

reappear in human oldsters: Methuselah would turn into a hairy ape.*

But this ghastly perspective does not concern us here.

* Huxley, After Many a Summer. Some physical characteristics in

the very old seem to indicate that the genes which could produce

such a transformation are still present in our gonads, but are

prevented from becoming active by the neotenic retardation of the

biological timeclock. The obvious conclusion is that prolongation

of the human lifespan is only desirable if it can be accompanied

by techniques which exert a parallel influence on the genetic clock.

retreat from specialised adult forms of bodily structure and behaviour,

to an earlier or more primitive, but also more plastic and less committed

stage -- followed by a sudden advance in a new direction. It is as

if the stream of life had momentarily reversed its course, flowing

uphill for a while, then opened up a new stream-bed. I shall try to

show that this

reculer pour mieux sauter

-- of drawing back to leap,

of undoing and re-doing -- is a favourite gambit in the grand strategy

of the evolutionary process; and that it also plays an important part

in the progress of science and art.

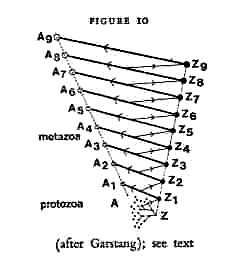

is meant to represent the progress of evolution by paedomorphosis. Z

to Z9 is the progression of zygotes (fertilised eggs) along the

evolutionary ladder; A to A9 represents the adult forms resulting from

each zygote. Thus the black line from Z4 to A4, for instance, represents

ontogeny, the transformation of egg into adult; the dotted line from A to

A9 represents phylogeny -- the evolution of higher forms. But note that

the thin lines of evolutionary progress do not lead directly from, say, A4

to A5 -- that would be gerontomorphosis, the evolutionary transformation

of an adult form. The line of progress branches off from the unfinished,

embryonic stage of A4. This represents a kind of evolutionary retreat

from the finished product, and a new departure towards the evolutionary

novelty Z5-A5. A4 could be the adult sea cucumber: then the branching-off

point on the line A4-Z4 would be its larva; or A8 could be the adult

primate ancestor of man, and the branching-off point its embryo --

which is so much more like the A9 -- ourselves.

the evolution of

ideas

. The emergence of biological novelties

and the creation of mental novelties are processes which show certain

analogies. It is of course a truism that in mental evolution, social

inheritance through tradition and written records replaces genetic

inheritance. But the analogy goes deeper: neither biological evolution

nor mental progress follows a continuous line from A6 to A7. Neither of

them is strictly cumulative in the sense of continuing to build where the

last generation has left off. Both proceed in the zigzag fashion indicated

in the diagram. The revolutions in the history of science are successful

escapes from blind alleys. The evolution of knowledge is continuous only

during those periods of consolidation and elaboration which follow a major

break-through. Sooner or later, however, consolidation leads to increasing

rigidity, orthodoxy, and so into the dead end of overspecialisation --

to the koala bear. Eventually there is a crisis and a new 'break-through'

out of the blind alley -- followed by another period of consolidation,

a new orthodoxy, and so the cycle starts again.

is not built on top of the previous edifice; it branches out from the

point where progress has gone wrong. The great revolutionary turns in

the evolution of ideas have a decidedly paedomorphic character. Each

zygote in the diagram would represent the seminal idea, the seed out of

which a new theory develops until it reaches its adult, fully matured

stage. One might call this the ontogeny of a theory. The history of

science is a series of such ontogenies. True novelties are not derived

directly from a previous adult theory, but from a new seminal idea --

not from the sedentary sea urchin but from its mobile larva. Only in

the quiet periods of consolidation do we find gerontomorphosis -- small

improvements added to a fully grown, established theory.

in evidence: Garstang's diagram could have been designed to show how

periods of cumulative progress within a given 'school' and technique

end inevitably in stagnation, mannerism or decadence, until the crisis

is resolved by a revolutionary shift in sensibility, emphasis, style.*

* See The Act of Creation, Book One, Chapters X and XXIII.

that it has a solid factual basis. Biological evolution is to a large

extent a history of escapes from the blind alleys of overspecialisation,

the evolution of ideas a series of escapes from the bondage of mental

habit; and the escape mechanism in both cases is based on the principle

of undoing and re-doing, the draw-back-to-leap pattern.

our starting point, the monkey at the typewriter. The monkey, according

to the orthodox doctrine, is supposed to proceed by hit and miss, just

as mental evolution, according to Behaviourist doctrine, is supposed

to proceed by trial and error. In both cases, progress is secured by

the stick-and-carrot method: the successful tries are rewarded by the

carrot of survival or of 'reinforcement'; the harmful ones are weeded

out by the stick of extinction, or by 'negative reinforcement'.

error are inherent in all progressive development. But there is a world

of difference between the random tries of the monkey at the typewriter,

and the various directive processes summarised in preceding chapters --

starting with the hierarchic controls and regulations built into the

genetic system, and culminating in the draw-back-to-leap pattern of

paedomorphosis. The orthodox view implies reeling off the available

responses in the animal's repertory, or on the Tibetan prayer-wheel of

mutations, until the correct one is hit upon by chance. The present view

also relies on trial and error -- each escape from a blind alley followed

by a new departure is just -- that but of a more complex, sophisticated

and purposive kind: a groping and exploring, retreating and advancing

towards higher levels of existence. 'Purpose', to quote H.J. Muller again,

'is not imported into Nature. . . . It is simply implicit in it.' [8]

known for some time, but their implications have mostly been ignored

by orthodox evolutionists. Yet if these isolated facts and theories

are worked into a synthesis, they make the problem of evolution

appear in a new light. There may be a monkey hammering away at the

typewriter, but that device is organised in such a way as to defeat

the monkey. Evolution is a process with a fixed code of rules, but

with adaptable strategies. The code is inherent in the conditions

of our planet; it restricts progress to a limited number of avenues;

while at the same time all living matter strives towards the optimal

utilisation of the offered possibilities. The combined action of these two

factors is manifested on each successive level: in the micro-hierarchy

of the gene-complex, the canalisation of embryonic development, and

its stabilisation by developmental homeostasis. Homologue organs --

evolutionary holons -- and similar animal forms arise from independent

origins and provide archetypal unity-in-variety. The initiative of

the animal, its curiosity and exploratory drive, act as pacemakers of

progress; a quasi-Lamarckian mechanism of inheritance may in rare cases

come to its aid; paedomorphosis offers an escape from blind alleys and a

new departure in a different direction; and lastly, Darwinian selection

operates within its limited scope.

trigger which releases the coordinated action of the system; and to

maintain that evolution is the product of blind chance means to confuse

the simple action of the trigger with the complex, purposive processes

which it sets off. Their purposiveness is manifested in different ways on

different levels of the hierarchy; on each level there is trial and error,

but on each level it takes a more sophisticated form. Some years ago,

two eminent experimental psychologists, Tolman and Krechevsky, created

a stir by proclaiming that the rat learns to run a maze by forming

hypotheses. [9] Soon it may be permissible to extend the metaphor and

to say that evolution progresses by making and discarding hypotheses,

in the process of spelling out a roughed-in idea.

We are all in the gutter,

but some of us are looking at the stars.

Oscar Wilde

ingenious improvisations, according to the challenge they face.* Other

things being equal, a monotonous environment leads to the mechanisation of

habits, to stereotyped routines which, repeated under the same unvarying

conditions, follow the same rigid, unvarying course. The pedant who has

become a slave of his habits thinks and acts like an automaton running

on fixed tracks; his biological equivalent is the over-specialised animal

the koala bear clinging to his eucalyptus tree.

* See Chapter Eight.

which can only be met by flexible behaviour, variable strategies,

alertness for exploiting favourable opportunities. The biological parallel

is provided by the evolutionary strategies discussed in previous chapters.

no longer be met by the organism's customary skills. In such a major

crisis -- and both biological evolution and human history are punctuated

by such crises -- one of two possibilities may occur. The first is

degenerative

-- leading to stagnation, biological senescence,

or sudden extinction as the case may be. In the course of evolution this

happened over and again; to each surviving species there are a hundred

which failed to pass the test.

Part Three

of this book discusses the possibility that our own species is facing

a crisis unique in its history, and that it is in imminent danger of

failing the test.

regenerative

Other books

Beneath the Surface by Melynda Price

Batman 5 - Batman Begins by Dennis O'Neil

The Far Side of Lonesome by Rita Hestand

Only Love by Elizabeth Lowell

This is Your Afterlife by Vanessa Barneveld

Liar by Justine Larbalestier

Handle With Care by Josephine Myles

Witch & Curse by Nancy Holder, Debbie Viguié

The Lost Gods by Francesca Simon

Shadow of the Lords by Simon Levack