The General's Son: Journey of an Israeli in Palestine (6 page)

Read The General's Son: Journey of an Israeli in Palestine Online

Authors: Miko Peled

Tags: #BIO010000

She refused to take another family’s home. “That I should take the home of a family that may be living in a refugee camp? The home of another mother? Can

you imagine how much they must miss their home?” She told me this story many times as a child, insisting that I hear her message. “I refused, and we all stayed living with Savta Sima, which was not easy for any of us. And to see the Israelis driving away with loot, beautiful rugs and furniture. I was ashamed for them; I don’t know how they could do it.”

By refusing the house in Katamon, she gave up an opportunity to have a beautiful, spacious home for her family in a choice neighborhood in Jerusalem, and at no expense. It wasn’t until many years later that my father’s military paycheck could afford them a comfortable house, and even then it came at some sacrifice and with help from my grandmother Sima. I wish I could recall the first time my mother told me this story, but I can’t. I only know that I’ve known it for as long as I can remember myself.

After the war ended, my father was asked to remain in the army as an officer. He was sent back to England, this time to the Royal Military Academy at Sandhurst. By then, Nurit had been born, and the four of them spent one year in England. When my father came back from England, he was assigned to a team of officers, all graduates of the Royal Military Academy, who established the Israeli army’s Senior Staff College. In 1954, he was part of the first Israeli military delegation to visit the United States.

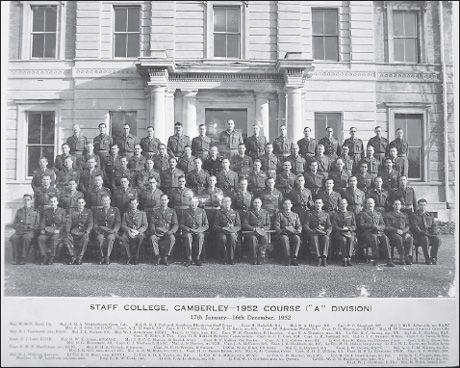

My father attended the Senior Staff College at Camberly in 1951.

My father at Camberly (seated on the right at the end of the first row).

My father participated in the first military delegation to visit the United States. Here with Haim Hertzog, Yitzhak Rabin and Moshe Dayan.

Political rivalries and upheaval in Israel during the mid-1950s determined, to a large degree, the relationship between the elected civilian government and the army—and also impacted my father’s career. One could roughly categorize two main approaches to Israeli-Arab relations within the ruling labor movement. There was a moderate, diplomatic approach led by Moshe Sharett, Israel’s first foreign secretary and then its second prime minister. Sharett believed Israel should avoid war and seek a negotiated peace settlement with its Arab neighbors. There was also an aggressive approach that wanted to establish Israel as the supreme military force in the region, so that it would never need to negotiate a peace settlement. David Ben-Gurion, who was Israel’s first prime minister, led this approach and was supported by the army’s senior command. In 1953, Ben-Gurion decided to resign as prime minister, leave politics, and live in a remote desert outpost in the southern part of the country, allowing Moshe Sharett to take his place.

Then in 1955, as a result of a failed covert military intelligence operation in Egypt and the resignation of Defense Minister Pinhas Lavon, Ben-Gurion returned to politics as defense minister. As soon as he returned, he and army Chief of Staff General Moshe Dayan tried to advance a plan for an Israeli attack on Egypt. Prime Minister Sharett was opposed to the plan and led an effective coalition and succeeded in derailing it. This infuriated Ben-Gurion. When general elections were held in July of that year, Ben-Gurion ran a tough campaign and won back the prime minister’s seat. In a political “musical chairs” that is quite common in Israeli politics, Sharett was now once again foreign minister. But Sharett posed a problem for Ben-Gurion. He stood firm in his opposition to Ben-Gurion’s plan to attack Egypt, a plan Sharett believed would lead to an unnecessary all-out war, and he foiled several of Ben-Gurion’s attempts to engage in military operations. Finally, Ben-Gurion fired Sharett. Moderates and liberal-leaning people within Israeli society who viewed Sharett as “the last bastion of moderation” were furious, but Ben-Gurion’s decision was irreversible.

In 1956, with Sharett out of the way, Ben-Gurion signed a secret pact with France and Britain to attack Egypt. Israel conquered the Gaza Strip and the Sinai Peninsula in what was called the Sinai Campaign, or

Mivtza Kadesh

. The war lasted from October 29 to November 5. Israel suffered 171 casualties, and the Egyptians lost between two and three thousand men. Israel captured 6,000 POWs and the Egyptians captured four Israelis. Just as Ben-Gurion and Dayan had anticipated, it was a devastating blow to the Egyptian army.

This was the first time Israel had occupied the Gaza Strip—an artificially delineated region on the southeastern coast of the Mediterranean Sea surrounding the ancient city of Gaza—where Palestinians refugees exiled in 1948 were herded. After the Sinai Campaign, my father, by then a full colonel, was

appointed military governor of the Gaza Strip. This was a defining role for him, and it influenced his entire life.

My father did not usually have conversations with me or with my siblings. If he had something to say, he would lecture us and then get up and leave when he was done. For several years while I was in high school, his classes ran late into the evening, and he did not return home until close to midnight. Before going to sleep my mother would prepare a nice hot soup for him to have when he got home. I would often wait up for him, and we would both have a bowl of soup and talk.

It was during one of those late nights that he revealed to me his thoughts on his time in the Gaza Strip. “When I was given the orders that described my role as military governor, I was aghast. They were identical to those of the British high commissioner, or governor of Palestine. I was not only representing the foreign occupier, I was the governor. I could not help recall how I, as a young man, was determined to fight the British who ruled Palestine and whom I considered foreign occupiers. You really never know how things will turn out in this world.”

When I first went to the army archives in Tel Aviv to look for information about my father’s career, an employee who assisted me immediately recommended that I look up the Gaza Report. “It is one of the defining documents written by your father,” he said. In this document, he expresses how appalled he was when he entered Gaza to take up his command. I have come to recognize the document’s language and tone as my father’s voice: he comes across as clear, unemotional, and analytical, yet unyieldingly critical of his superiors and the military establishment in general.

It was several days after Gaza was captured that he was sent in. Chaos reigned: “Israeli soldiers and border police were there with no clear orders and no clear command center, which led to rampant disorder and looting.” My father quickly set up his command, arrested the looters, collected arms from the locals, and restored order. He set up guidelines to restoring basic services like healthcare and education. He conducted a census that accounted for each family, whether they were refugees and if so from what town or village they had been exiled. The report had accounts of education levels, property, livestock, and a whole host of information about the place and its people.

As military governor of hundreds of thousands of Palestinians, my father realized that he knew virtually nothing of their language, culture, or their way of life. He did not like the fact that he needed translators in order to communicate with the people he governed so he made a personal decision to study Arabic, receiving a bachelor’s degree in Arabic from the Hebrew University in Jerusalem. “In conversations with the locals, I was amazed to learn that they were not seeking vengeance for the hardship we caused them, nor did they wish to get rid of us. They were realistic and pragmatic and wanted to be free.”

Under immense pressure from the Eisenhower administration, Israel was forced to give up the conquered territories in March of 1957. Although in

those days Israel was receiving no money from the U.S. government, when the American president gave the word, my father had two weeks to get out. He was out in two days, but he was deeply troubled. My mother and my sister Nurit told me many times that this issue tormented him for months. “He could not sleep at night, and he would talk of nothing else,” Nurit said. My mother told me similar stories.

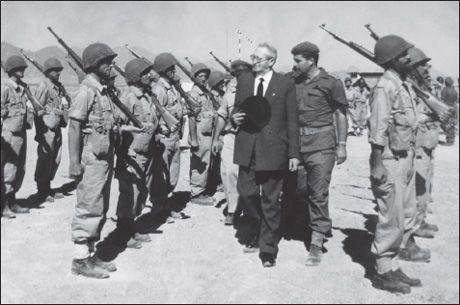

My father inspecting groups with Israel’s second president, Yitzhak Ben-Zvi.

I was not yet born, but I can imagine his frustration when he learned he would have to go back on his word. I heard him talk about this many years later, saying: “I was assured by my superiors that I could tell the people of Gaza that if they cooperated with us they would not be returned to Egypt. The local leadership believed me and cooperated and then when we left Gaza they paid a heavy price for this.”

In an article he wrote after he retired, he brought this up again:

As the one whose destiny it was to inform the leaders of the towns and villages in Gaza on that cold day in April 1957 that the Israeli government decided to forsake them, I can testify to the looks on the faces of people who at first did not want to believe what they were hearing and then realized what they had brought upon themselves by believing the Israeli government.

1