The First Tycoon: The Epic Life of Cornelius Vanderbilt (49 page)

Read The First Tycoon: The Epic Life of Cornelius Vanderbilt Online

Authors: T. J. Stiles

Tags: #United States, #Transportation, #Biography, #Business, #Steamboats, #Railroads, #Entrepreneurship, #Millionaires, #Ships & Shipbuilding, #Businessmen, #Historical, #Biography & Autobiography, #Rich & Famous, #History, #Business & Economics, #19th Century

In the 1850s Vanderbilt emerged as a major force on the stock exchange, often working closely with Daniel Drew. During this period stockbrokers conducted formal trades of securities in auctions in the Merchants' Exchange on Wall Street, shown here in 1850. Informal trades took place among unlicensed brokers on the curb outside.

Library of Congress

Vanderbilt's youngest son, George Washington Vanderbilt, entered West Point in 1855, graduated near the bottom of his class in 1860, and served briefly in the West. At the beginning of the Civil War, he was convicted by a court-martial of deserting his post. He died in France on December 31, 1863.

Library of Congress

Vanderbilt's respect for his son William grew in the late 1850s, as he became an officer of the Staten Island Railroad. Vanderbilt made him vice president of the Harlem Railroad, and eventually operational manager of all his lines. A gifted manager, William proved far less diplomatic than his father.

Library of Congress

Vanderbilt named the greatest vessel he ever constructed after himself. For a time the largest and fastest steamship afloat, the

Vanderbilt

shared the characteristics of all the steamships he designed: a nearly vertical bow, massive sidewheels, supplementary sails, and twin walking-beam engines adapted from steamboats.

Naval Historical Center

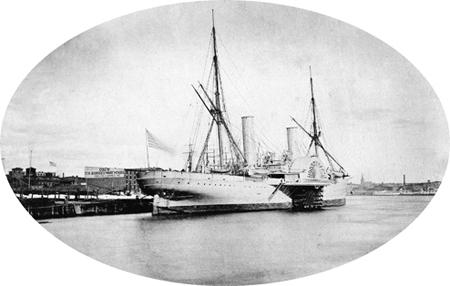

The

Champion

was the first iron-hulled steamship constructed in the United States. Though not the largest in Vanderbilt's fleet, it was fast and fuel efficient. During the Civil War it ran between Panama and New York, as part of a monopoly on California steamship traffic that Vanderbilt helped establish.

Library of Congress

The rampage of the Confederate ironclad

Virginia

(also known as the

Merrimack)

created a panic in Lincoln's cabinet. The

Monitor

rushed to the scene and battled it to a standstill, as shown here. But the

Virginia

survived. Its continuing threat led Secretary of War Edwin Stanton to ask Vanderbilt to equip the

Vanderbilt

to destroy it.

Library of Congress

Then the Commodore sprang his trap. On January 17, a headline in the

Times

announced, “

NEW LINE OF STEAMSHIPS TO SAN FRANCISCO

.” He was going to compete against Accessory Transit. The move epitomized the paradox that was Vanderbilt, for it was motivated by a personal vendetta yet had wide public consequences. The resulting fare war would dramatically reduce prices on the corridor between California and New York, showering benefits on migrants and merchants. It would also destroy Accessory Transit's profits, lay low the share price, and thus enrich Vanderbilt at the expense of his enemy—and innocent stockholders.

All these months, the Simonson shipyard had been refitting the

North Star

as a passenger liner. The world-famous yacht was to serve as the flagship of a new steamship fleet, but it would take time to build more vessels. So Vanderbilt made an alliance with merchant Edward Mills, who owned the

Uncle Sam

and built the new

Yankee Blade

with Vanderbilt's help. “These vessels are all known as exceedingly swift and commodious,” the

Times

reported; they would run on the Pacific, and connect to the

North Star

at Panama. Official notice of the “Vanderbilt Line for California” ran on January 23. With Daniel Allen in Europe, James Cross would manage the ships.

52

Interestingly, it was the Washington correspondent of the

Times

who broke the story. Vanderbilt had gone to the capital to add a third role to those of speculator and entrepreneur—that of lobbyist, in pursuit of the California mail contract. As early as October 10 he had written to Secretary of State William L. Marcy on the subject. Vanderbilt likely knew Marcy personally, and undoubtedly found the jowly former governor of New York appealing. Historian Allan Nevins judged Marcy “blunt, humorous,” and highly social. “A gentleman of the old school,” he reportedly coined the phrase “To the victor belong the spoils,” an apt summary of the Commodore's own code. Vanderbilt wrote to Marcy, “I feel some solicitude to enlarge my reputation by doing something valuable for the country,” and suggested that a transit across Mexico, farther north even than Nicaragua, could save two weeks on the mail to San Francisco.

53

Washington had been empty when Vanderbilt wrote to Marcy; in December Congress reassembled, and the capital came alive. “The hotels and boarding-houses filled up, the shopkeepers displayed a varied stock, and the deserted villages [that made up the city] coalesced into a bustling town,” Nevins wrote—though it was still “a fourth-rate town.” Since Washington existed entirely for the seasonal gathering of Congress and a mere handful of year-round civil servants (the entire State Department staff consisted of eighteen men), it had few attributes of a true city. It lacked proper water or sewage works; parks remained undeveloped tracts, overrun by weeds; most government buildings were small, drab brick structures; even the Capitol and the Washington Monument sat unfinished. The most common business seems to have been the boardinghouse. “Music and drama were so ill-cultivated,” Nevins noted, “that a third-rate vocalist or strolling troupe created a sensation.”

54

This was the town that Vanderbilt traveled to in January to press his war on Accessory Transit.

And to win glory for himself. The triumphant voyage of the

North Star

had swelled his sense of importance. It also seems to have soothed his strained relationship with his wife. Sophia acompanied him to Washington, where they socialized with Joseph L. Williams, a former Whig congressman whom Vanderbilt hired to assist in his lobbying. “The Commodore and lady were in pleasant spirits when here,” Williams wrote to a friend in New York. “I visited them several times at the hotel, and they went to see Mrs. [Williams] at our house, as she could not go out. I am to see the Secretary of the Navy for the Commodore by the time he comes back. Between you and I, he is anxious, or, rather,

ambitious

to build the government vessels.” Vanderbilt offered to build a “first-class steam frigate” for the navy; unlike most such proposals, his demanded no money up front, but merely repayment of the cost should the ship be accepted into the fleet.

This was patriotism, yes, but Vanderbilt hoped the positive publicity would strengthen his attempt to capture the contract for the California mail, to carry it by the aforementioned transit over Mexico, via Veracruz and Acapulco. As lobbyist Williams added in his letter, “He has other wishes in respect to the Vera Cruz and Acapulco route to California, to succeed in which he has to break down the prejudices of the Postmaster General and the elaborate arrangements of Jo White as to Nicaragua.”

55

Inevitably, Joseph White dashed to Washington as soon as he learned of Vanderbilt's lobbying mission. “We are having some excitement indoors just now, relative to California mail contracts,” the Washington correspondent of the

Times

reported on January 17. “Parties interested in the Ramsey [Mexico] route, the Panama route, and the Nicaragua route, are all upon the ground attending to their respective interests.” (Ramsey was a figure in the company trying to open the Mexican land transit that Vanderbilt hoped to link to with his ships.)

White did what he did best: insult Vanderbilt. He desired the mail contract for Accessory Transit, of course, but he wanted most to deny it to Vanderbilt. Together with Senator James Cooper, White called on Postmaster General James Campbell “for the purpose of impressing him with the advantage of the Nicaragua route and the worthlessness of any other, and especially the Ramsey route via Vera Cruz and Acapulco,” the

Times

wrote. “Postmaster-General Campbell says it is a waste of time to cry down the latter route in his presence, because his mind is decidedly and irrevocably made up against it, which of course is a great satisfaction to the Nicaragua people.”

56

The Commodore soon had more bad news. He returned to Washington in March with Sophia and daughter Phebe Cross, and discovered that his lobbyist Williams had fallen sick with tuberculosis—

“lung fever,”

as Williams called it. Vanderbilt carried on, one colleague recalled. “We wanted to see [Senator] John M. Clayton, and arranged to go and call on him on a certain evening. When night came… it rained pitchforks. I said to the Commodore, ‘We can't go now; wait, and if it slacks up we will go over.’” When the weather cleared, the friend couldn't find Vanderbilt, so he took the stage to Clayton's house. “I went in and found him, and the Commodore with him, playing whist.… He [Vanderbilt] said, ‘Between you and me, that's the way I got ahead of some of the other boys. I never failed to keep an engagement in my life.’”

57