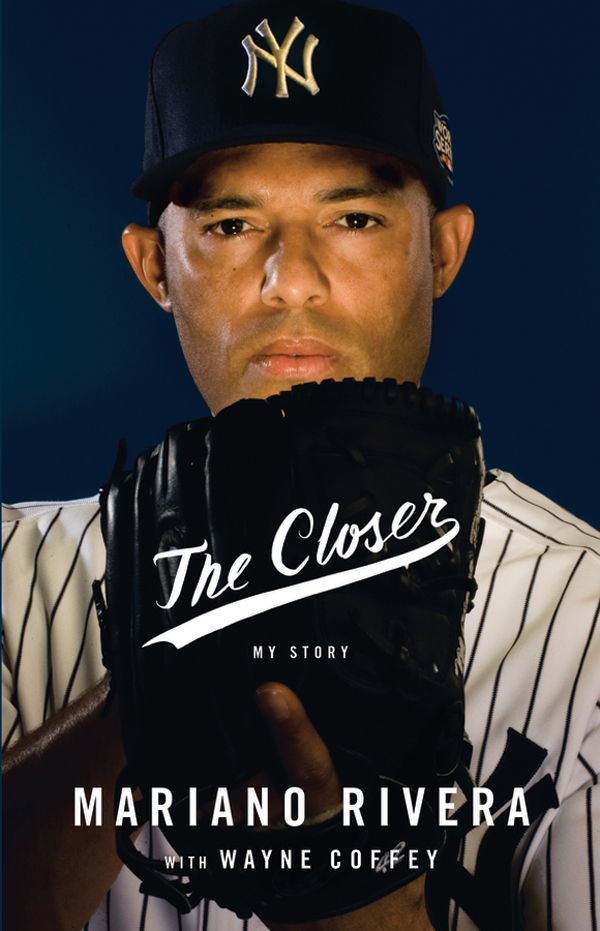

The Closer

Authors: Mariano Rivera

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Sports, #Rich & Famous, #Sports & Recreation, #Baseball, #General, #Biography & Autobiography / Sports, #Biography & Autobiography / Rich & Famous, #Sports & Recreation / Baseball / General

In accordance with the U.S. Copyright Act of 1976, the scanning, uploading, and electronic sharing of any part of this book without the permission of the publisher constitute unlawful piracy and theft of the author’s intellectual property. If you would like to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), prior written permission must be obtained by contacting the publisher at [email protected]. Thank you for your support of the author’s rights.

To my Lord and Savior, Jesus Christ,

and the family He has blessed me with:

My beautiful wife, Clara, and our

three wonderful boys, Mariano Jr., Jafet, and Jaziel

Y

OU DON’T MESS AROUND

with machetes. I learn that as a little kid—decades before I’d ever heard of a cut fastball, much less thrown one. I learn that you don’t just pick up one of the things and start swinging it as if it were a bat or a broomstick. You have to know how to use it, know the right technique, so you can be efficient and keep it simple, which, if you ask me, is always the best way to go, in all aspects of life.

Keep it simple.

My grandfather Manuel Giron teaches me everything I know about using a machete. We would head out into the sugarcane fields and he’d show me how to grip it—how to bend my knees and bring the blade around so it is level with the surface you want to cut, not a random whack but something much more precise. Once I get the hang of it, I cut our whole lawn with a machete. The lawn isn’t big—much closer to the size of a pitcher’s mound than an outfield—but I still cut every square inch of it with that hand-held blade. It takes an hour, maybe two. I don’t rush. I never rush. It feels good when I am done.

I do not have my machete with me on the late March morning in 1990 when I walk out into the rising sun and get the day’s first whiff of fish. I don’t think I will be needing it. I am twenty years old and I have just signed a professional baseball contract with the New York Yankees. I have no idea what this means.

None.

A few weeks earlier, a Yankee scout named Herb Raybourn sits in the kitchen of our two-room cement home. The house has a tin roof and a couple of chickens out back and sits on a hill in Puerto Caimito, the poor little Panamanian fishing village where I’ve lived my whole life. My parents sleep in one room, and the kids, all four of us, sleep in the other.

Before Herb arrives, I have a quick talk with my father.

A gringo wants to talk to you about me playing pro baseball, I say. I don’t know much more than that.

Let’s listen to what he has to say, my father says.

Herb is actually Panamanian and speaks Spanish, even though he looks white. He puts some papers on the table. He looks at me, then my father.

The New York Yankees would like to sign you to a contract and can offer you $2,000, Herb says. We think you are a young man with talent and a bright future.

Herb adds that the Yankees will include a glove and baseball cleats in the deal. I am making $50 a week working on my father’s commercial fishing boat. This is not a negotiation. It is what the New York Yankees are offering, the only number that would be mentioned.

Because you are twenty, we’re not going to send you to the Dominican Republic, the way we do with teenagers, Herb says. We’re going to send you right to Tampa for spring training.

I believe I am supposed to take this as good news, but Herb has no clue how clueless his new signee is. I have never heard of Tampa. I know almost nothing about the Dominican Republic. My world isn’t just small. It is the size of a marble. The biggest trip of my life to that point is a six-hour car ride to the border of Costa Rica.

Honest to goodness, I think that when the Yankees sign me I will continue to play my baseball in Panama. I figure that maybe I’ll move to Panama City, get a little upgrade in uniform, along with a legit glove and a pair of shoes that don’t have a hole in the

big toe—like the ones I’d had my Yankee tryout in. I’ll get to play ball and make a little money for a while, and then go off to mechanic’s school. That is my plan.

I am pretty good at fixing things. I like fixing things. I am going to be a mechanic.

The extent of my knowledge of the big leagues—

las Grandes Ligas

—is close to nothing. I know it is where Rod Carew, Panama’s greatest ballplayer, once played. I know there are two leagues, American and National, and that there is a World Series at the end of the season. I do not know much more than that. I am already in the major leagues when I overhear somebody talking about Hank Aaron.

Who’s Hank Aaron? I ask.

You’re not serious, the guy says.

Yes, I am. Who is Hank Aaron?

He’s baseball’s all-time home run leader, the guy who hit 755 homers to beat Babe Ruth’s record.

Who’s Babe Ruth? I ask.

The guy mutters something and turns away, knowing better than to try Honus Wagner on me.

So Herb has to spell everything out for me, a kid as skinny as a Q-tip, and utterly naive: No, you won’t be staying in Panama. When you sign with a big league organization, the deal is that you move to the United States. You go buy some shirts and underwear and a cheap suitcase. You get a work visa and try to act as if you know what you are doing when you are filling out the paperwork. You will be scared and nervous and sad and have no idea how you are going to manage in a foreign country when all you know how to say is, “I no speak English.”

It isn’t just daunting. It’s terrifying. I try not to let on. I have always been good at hiding my feelings.

Weeks pass. The plane ticket to Tampa arrives. Now it is getting real.

Now it is time.

Let’s go, Pili, my mother says. Pili is the name my sister, Delia, gave me when I was a baby. Nobody knows why. It’s what my family has called me my whole life. My father starts up his white Nissan pickup truck. Turbo is our name for it. It’s ten years old, rusty and battered and not anybody’s idea of a race car, but we still call it Turbo. Clara Diaz Chacón, my longtime girlfriend, is sitting between my father, Mariano Sr., and my mother, also named Delia. I throw my new suitcase in the flatbed and then climb in myself, along with my cousin Alberto. My father puts Turbo in reverse and we pull out of the driveway, onto Via Puerto Caimito, the one road in and out of our village, the only road that is paved. All the rest are dirt, most of them looking more like paths than anything you would drive on. We proceed through Chorrera, a much bigger town five miles away, and then make our way on a twisty, rutted road, past goats and plantain trees and swatches of rain forest, Alberto and I bouncing around in the back as if we were coconuts, anchored by nothing, only a skimpy railing stopping us from tumbling out.

I know where

we

are going—Tocumen International Airport in Panama City—but I am much less certain about where

I

am going.

I am a high-school dropout. I don’t even make it out of ninth grade in Pedro Pablo Sanchez High School, a U-shaped building in the heart of Chorrera with three floors and a courtyard in the middle, and dogs sleeping wherever they can find shade. It is a terrible decision to leave school, but I get fed up one day and just bail on it, walking right out past the dogs in my pressed blue trousers and crisp white shirt. (I iron the uniform myself; I like things to be neat.) I am not thinking through any of the consequences of walking out of school, and I am not getting much direction from my parents, working-class people who are smart but not very familiar with formal education.

My last school lesson—and the last straw—comes in Mrs. Tejada’s math class. At least I think that’s her name, but honestly I

am a bit fuzzy about that, just because I try not to think about her very much. She isn’t my biggest fan, and she doesn’t try to hide it, glaring at me as if I were the bane of her teaching life. I hang around with kids who aren’t full-fledged troublemakers but are definitely into mischief. It is guilt by association, I guess. One day a few of us are fooling around in the back of the classroom, paying little attention to the Pythagorean theorem and a lot of attention to a kid we are giving the business to. One of my friends crumples up a piece of paper and tosses it at the kid, hitting him in the head.

Hey, cut it out, the kid says.

I do no throwing, but I do do some laughing.

Mrs. Tejada notices.

Rivera! She always calls me by my last name.

Why did you throw that?

I didn’t throw anything, I reply.

Don’t tell me you didn’t throw it. Now come up here.

I didn’t do anything wrong. I am not going anywhere.

Rivera, come up here! she repeats.

Again, I do not obey her command, and now she is really ticked off. I am no longer a mere paper-thrower. I am an all-out insubordinate. She walks to my desk and stands over me.

You are to leave this classroom right now, she says, then escorts me out into the hallway, where I spend the rest of math class, definitely doing no math.

After I walk out that day, I wind up being suspended for three days, and I never return to Pedro Pablo Sanchez High School. I never see Mrs. Tejada again, either, until I run into her in a market after I’d been in pro ball for several years.

Hi, Mariano, she says. Congratulations on your baseball career. I’ve followed how well you are doing.

There is no glare. No scolding voice. She greets me with a warmth I’ve never seen from her before.

Is this really Mrs. Tejada, or just a Mrs. Tejada look-alike with a much better disposition?

I think.

I smile weakly. It is the best I can do. I’ve never liked it when people treat you according to how successful or prominent you are. The whole time I was in her class, she regarded me as a borderline juvenile delinquent. Maybe I wasn’t going to make anybody forget Albert Einstein, but I was nowhere near the kid she had typecast me as.

Please don’t act like you care about me and like me now when you didn’t care about me or like me when I was a student,

I think.

Thanks, I say, heading right past her to the fruit aisle, hoping she gets the message.

But Mrs. Tejada isn’t really the main reason I dropped out. The bigger problem is the fights, which are a regular occurrence. I enjoy learning and do pretty well in school, but the fights just get to be too much. In the hallways, in the schoolyard, on the way back home—they break out everywhere, almost always for the same reason, kids teasing me that I smell like fish:

There he goes, the fishy boy.

Hold your nose, the fish are getting closer.

I thought we were in school, not on the fishing boat.

My tormentors are right. I do smell like fish. Plenty of Puerto Caimito kids do. We live by the water, not far from a processing plant that makes fish meal out of sardines—or

harina de pescado,

as we call it. My father is a captain on a commercial fishing boat, his twelve-plus-hour workdays spent throwing his nets and hauling in all the sardines and anchovies he can. The smell of fish overpowers everything in Puerto Caimito. You could shower for an hour and plunge yourself in cologne, and if a droplet or two of water from the fish plant touches your clothes, you are going to stink all night. Fish keep the local economy from drowning. Fish are what supply jobs for many of the parents of the kids who are taunting me. I could’ve, should’ve, ignored them. I do not.

They bait me, and then they reel me in. I’m not proud of this. It’s really dumb on my part. My grandmother had just died and I am a little adrift, and get overcome by a self-destructive impulse. I should’ve finished out the school year, should’ve turned the other cheek, as the Bible teaches. I do not know much about the Bible at this point. I do not know the Lord at all. I am young and headstrong, intent on doing things my own way. His way? The power of Scripture?

I am not there yet.

We continue the drive to the airport. On the autopista, I feel the warm air rushing into my face in the back of the pickup. I am getting sadder. We drive past groves of cassava and pineapple trees, and the occasional cow, and it’s almost as if my boyhood is passing by, too. I think about playing ball on the beach with a glove made from a milk carton, a bat made from a stick, and a ball made from tightly wound fishing nets. I wonder if I’ve played my last game on El Tamarindo, another dirt patch of a ball field where I played, a field named for the tamarind tree by home plate. I think about what would’ve happened if I’d kept playing soccer, my first sporting love, trying to beat defenders with a ball attached to my foot (with or without shoes), imagining myself the Panamanian Pelé, a dream that lasted until I got smacked in the eye with the ball during a game and temporarily lost vision. I kept playing and, twenty minutes later, went up for a header, collided with a guy, and wound up in the emergency room, where the doctor closed the cut and told me the eye looked very bad and needed to be seen by a specialist.

My soccer career didn’t go for very much longer.

We are just a half hour away now. I look into Turbo’s cab, at Clara sitting between my parents. Clara is always close by, steadfast and strong. You know how it is with some people, that you can just feel their strength, their goodness? That is how I feel about Clara. We grow up just a few houses apart in Puerto Caimito; I’ve known her since kindergarten. Friendship turns to romance on the

dance floor of a club one night. Clara had not spoken a word to me since I’d dropped out of school. She would even move in the other direction if she saw me coming. I think—no, I know—she is disappointed that I’d just quit like that. I think she expects more from me. The deep freeze lasts until a bunch of us guys and girls are together in the club, and Clara and I wind up dancing. The lights are low. The beat pulses hard. As the dance is ending, I am about to head off the floor when our eyes lock. She reaches out for my wrist. I can’t really describe what happens in that moment. We don’t dance the rest of the night together. I don’t walk her home and we don’t have our first kiss beneath swaying palm trees, or in the midnight quiet of El Tamarindo.

But something happens. Something powerful. It is the Lord who brings us together, I am as sure of that as I am sure that my name is Mariano Rivera. It was, and is, the will of the Lord that Clara and I are together. Why else would she have started speaking to me again? Why else would she have even been at the club that night? She hardly ever went to clubs, didn’t like the club scene much at all. But there we were, dancing, a connection being forged even though neither of us knew it at the time. You can call it a coincidence if you like, a random spin of the universe’s roulette wheel, but I believe the Lord has a plan for us, and this is the start of it.