The Firebrand and the First Lady: Portrait of a Friendship: Pauli Murray, Eleanor Roosevelt, and the Struggle for Social Justice (55 page)

Authors: Patricia Bell-Scott

Tags: #Political, #Lgbt, #Biography & Autobiography, #History, #United States, #20th Century

· · ·

ON DECEMBER 4, 1982

, Murray, Lash, and

Franklin D. Roosevelt Jr. joined a gathering of scholars, journalists, and former Roosevelt administration staffers at

Hunter College for a conference on the role of the first lady. It was the first major conference on the subject. More than seven hundred people attended. Lash spoke from a biographer’s perspective; Franklin Roosevelt, as a son.

Murray, introducing herself as a former “

youthful challenger and critic” of

ER’s, recalled the early days of their relationship.

For me, becoming friends with Mrs. Roosevelt was a slow, painful process, marked by sharp exchanges of correspondence, often anger on my side and exasperation on her side, and a gradual development of mutual admiration and respect. On the one hand, Mrs. Roosevelt was a mother figure to me; she and FDR were of the same generation as my own parents; they were also Episcopalians; they had six children as did my own parents, born roughly in the same period as the six Murray children.… I felt that Mrs. Roosevelt was a woman of deep religious commitment. And all these qualities made me feel very close to her in spite of myself.

The result of my rebellion was that Mrs. Roosevelt thought of me as “a firebrand” who had done some “foolish things” and who should not “push too fast,” while I took it upon myself to challenge her behavior in the area of race relations as an important figure and a part of an Administration which was moving too slow.

Previously, Murray had been reluctant to talk publicly about her friendship with ER. Here, Murray hit her stride. Of ER’s impact on her life, she said,

I learned by watching her in action over a period of three decades that each of us is culture-bound by the era in which we live, and that the greatest challenge to the individual is to try to move to the very boundaries of our historical limitations and to project ourselves toward future centuries. Mrs. Roosevelt, a product of late nineteenth century Victorianism, did just that, and she moved far beyond many of her contemporaries. I like to think that I am one of the young women of her time, touched by her spirit of commitment to the universal dignity of the human being created in the image of God (which we theologians call

imago dei

). Hopefully, we have picked up the candle that she lighted in the darkness and we are trying to carry it forward to the close of our own lives.

66

“Eleanor Roosevelt Was the Most Visible Symbol of Autonomy”

I

n 1984, Pauli Murray and

Maida

Springer-Kemp, both retired septuagenarians, embarked on “

a joint venture in cooperative yet autonomous living.” They moved into an old house with “

twin apartments” in the

North Point Breeze section of Pittsburgh. Maida lived on the first level, and Pauli occupied the upstairs unit. North Point Breeze was a

friendly, racially integrated neighborhood, rich in architectural history, less than thirty minutes from downtown Pittsburgh. It was an ideal location for Murray, who loved to walk in Westinghouse Park with

Christy, an elderly Doberman she adopted after

Roy died, to the Homewood Branch of the Carnegie Library, and on the University of Pittsburgh campus.

Life in North Point Breeze nurtured Murray’s

writing.

By the year’s end, she had completed a draft of her autobiography and finished half the revisions her editor had recommended. Murray’s social life was enriched by her relationships with Maida’s son

Eric Springer, who had become a distinguished attorney; his wife, Cecile, a highly regarded regional planner; and the congregation at the

Church of the Holy Cross.

After years without sufficient funds or time for leisure travel, Pauli took an Amtrak train tour to

Seattle with Maida. They stopped at the

Wingspread Center in Racine, Wisconsin, for a black women’s conference and a “

joyful reunion” with

Aileen Clarke Hernandez, who, like

Patricia Roberts Harris, had participated in the

Howard University student

restaurant boycott. In Seattle, Pauli spoke at the

Urban League’s annual dinner, and the

Coalition of Labor Union Women honored Maida at a luncheon.

When they were not being feted by their hosts—

Mona H. Bailey, a former

national president of Delta Sigma Theta sorority (Murray had become an honorary member), and the sorority’s ninety-five-year-old cofounder

Bertha Pitts Campbell—Pauli and Maida “

gorged” themselves in first-class restaurants. On the way home, they visited Pauli’s former editor,

Elizabeth Kalashnikoff.

The “

high point” of 1984 was Murray’s participation in

“

The Vision of Eleanor Roosevelt: Past, Present, Future,” a conference commemorating the centennial of

ER’s birth. This event was held at

Vassar College on October 13–16 and was cohosted by the Eleanor Roosevelt Institute. Each session addressed one of ER’s concerns: human rights, civil rights,

women’s rights, peace, or economic justice.

Among the presenters were Roosevelt family members;

Joseph Lash and his wife, Trudy;

Edna P. Gurewitsch, the wife of ER’s personal physician

David Gurewitsch; Henry

Morgenthau III, the executive producer of

Prospects of Mankind

, which ER had hosted for public television; and Murray’s friend Caroline

Ware. Reverend Gordon

Kidd, who had presided at the

funerals of Franklin and Eleanor Roosevelt, led the Sunday convocation, at which

Dorothy Height spoke and the

West Point Gospel Choir sang. In addition to Murray and Height, the African American speakers included historian and U.S. civil rights commissioner

Mary F. Berry, political scientist

Charles Hamilton, and

Bayard Rustin, director of the A. Philip Randolph Institute.

Murray joined ER’s grandson

John R. Boettiger, Edna Gurewitsch, Henry Morgenthau, former assistant secretary of labor

Esther Peterson, and U.N. Association of the U.S.A. staffer Estelle Linzer on a plenary panel entitled

“A

Remembrance of Eleanor Roosevelt.” Murray regaled the audience with memories of her first face-to-face conversation with ER the afternoon she hosted the National Sharecroppers Week delegation in her

New York City apartment, ER’s campaign inside the White House to save the life of

Odell Waller, and the weekend ER braved

Hurricane Hazel to keep a speaking engagement at

Bard College.

ER’s contribution to the modern women’s movement was the subject of considerable debate.

Some conferees claimed she was not a

feminist by virtue of her opposition to the

National Woman’s Party and the

Equal Rights Amendment.

Ms

. magazine cofounder

Gloria Steinem disagreed. Because ER had used her power and position to fight injustice, Steinem argued, the former first lady was “

definitely a feminist.”

Murray had strong opinions about this issue, too, and she weighed in on the debate:

While Mrs. Roosevelt’s brand of feminism did not lead her to give active support to the Equal Rights Amendment which she and many women reformers had earlier opposed for fear the adoption of ERA would undermine state protective labor laws for women, by the 1950’s she had dropped her strong objections to a constitutional guarantee of equality. Also, while the [President’s] Commission [on the Status of Women] itself did not recommend ERA, several of the women who worked with the Commission under her leadership, including myself, were the founders of the NOW which became the foremost advocate of ERA.…

Perhaps Mrs. Roosevelt’s greatest contribution to feminism during the forty years, which spanned the period from securing the vote for women in 1920 to the resurgence of the women’s movement in the 1960’s, was the example she set.… Eleanor Roosevelt was the most visible symbol of autonomy and therefore the role model of women of my generation. Although she did not live to see many of the spectacular gains—both substantive and symbolic—women have made in the past two decades, her own life and work pointed the way and helped to set in motion forces which made these gains possible. Just as she became the First Lady of the World, in a very real sense she was also the Mother of the Women’s Revolution.

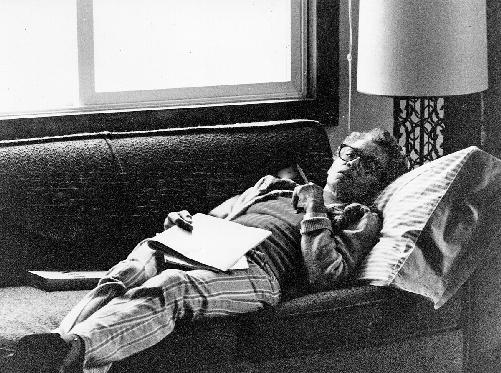

Pauli Murray at the home of her Hunter College classmate Louise E. Jefferson, in Litchfield, Connecticut, circa May 1985. They had stayed in touch through the years and this is one of the last photographs taken before Murray’s death.

(Photo by Louise E. Jefferson, Patricia Bell-Scott Collection)

67

“All the Strands of My Life Had Come Together”

P

auli Murray’s appearance at the Eleanor Roosevelt centennial conference proved to be her swan song. In December 1984, doctors discovered an obstruction in the bile duct leading into her pancreas. Preliminary tests indicated

pancreatic cancer. Shortly after her admission to

Pittsburgh’s Presbyterian University

Hospital on January 28, 1985, she lost consciousness. She was comatose for eight days and not expected to live. Her lung power was so diminished she had to use a breathing machine to keep pneumonia at bay. It took her a month before she could walk without assistance again. By the time she regained full awareness, she was only eighty-five pounds, twenty pounds below her ideal

weight. “

That I am among the living at all is a miracle of God’s loving providence,” she wrote in the spring to friends and family.

During Murray’s extended hospitalization, her dog,

Christy, died of old age. The loss of her pet, her failing health, and her fierce

smoking addiction sent Murray into a tailspin. Determined to be seen as more than a cancer victim, she had a sign posted over her hospital bed that read, “

Please refer to this patient as the Reverend Dr. Pauli Murray.”

She came home on March 8 “

to a shining place, flowers, and a ‘fatted calf.’ ” This homecoming, the daily calls, the heartwarming prayers, the avalanche of telegrams and get-well cards, and the

friends and family who came “

in shifts” to help brought her to tears. “

From here on out,” she vowed, “it’s a day at a time.”

Having nearly succumbed on the operating table, Murray began to prepare for the inevitable.

She sent the

crucifix she wore at her

ordination to

Dovey Johnson Roundtree, a friend, fellow activist, and Howard University School of Law alumna who was assistant pastor at Allen Chapel African Methodist

Episcopal Church, in Washington, D.C.

Murray gave Maida an original painting by Louise

Jefferson. And when

Ruth Powell, co-leader of the 1943–44 Howard University student

boycott campaign, flew to Pittsburgh to see Murray, she insisted that Powell take her wheeled luggage cart since she “

wouldn’t be needing it.” Murray was correct.

She would be too weak to attend the upcoming

Hunter College graduation ceremony, where she, former Democratic vice presidential candidate

Geraldine Ferraro, and artist

Robert Motherwell would receive

honorary doctorates.

Pauli had often prayed all night at the bedside of congregants and loved ones, as was the case when Maida’s mother,

Adina Stewart Carrington, passed.

When Pauli drew her last breath, Maida was at her side. Pauli departed peacefully at home in Pittsburgh on July 1, 1985. She was seventy-four.

· · ·

PAULI MURRAY HAD BEEN

a lifelong student of history, and she had often thought about how her life intersected with other agents of social change. She considered it no accident that the

NAACP published the inaugural issue of

The Crisis

, under the editorship of “the great protagonist of civil rights”

W. E. B. Du Bois, in the same month and year of her

birth. It pleased her to discover “

that the great Russian novelist and advocate of

nonviolence,

Leo Tolstoy…died within twenty-four hours” of her birth. That Murray’s

memorial service took place on the forty-third anniversary of the funeral of

Odell Waller, the black sharecropper whose execution marked a defining moment in her relationship with Eleanor

Roosevelt, was another historical coincidence she would have surely noted.

On July 5, at eleven o’clock in the morning, 141 people attended a Mass of the Resurrection held, as

Murray had requested, at the

Washington National Cathedral. Murray’s minister, Canon

Junius F. Carter, officiated. Reverends

Phoebe Coe,

Becky Dinan,

Doris Mote,

Diane Shepard,

Beverly Moore-Tasy, and

Barbara Harris were cocelebrants. Canon Carter said of Murray, “

The power she had and the effect her life had on all of us was a glorious experience.” Murray’s nephew Michael, who delivered a stirring tribute from the

family, said, “

It was Aunt Pauli’s habit to speak the truth, no matter what the consequences.” After the Mass, members of the Delta Sigma Theta sorority conducted their traditional Omega Omega farewell ritual in the courtyard.

Murray had asked that she be cremated and interred at the cathedral, but her ashes were buried in Brooklyn’s

Cypress Hills Cemetery, in a family plot with

Aunts Pauline and Sallie, Renee

Barlow, and Renee’s mother, Mary Jane. This burial ground placed Murray in good company, for it was the site

George Washington chose for a military fortification during the Revolutionary War. This cemetery was also the final resting place for Murray’s hero, the baseball Hall of Famer and civil rights activist

Jackie Robinson.