The Firebrand and the First Lady: Portrait of a Friendship: Pauli Murray, Eleanor Roosevelt, and the Struggle for Social Justice (51 page)

Authors: Patricia Bell-Scott

Tags: #Political, #Lgbt, #Biography & Autobiography, #History, #United States, #20th Century

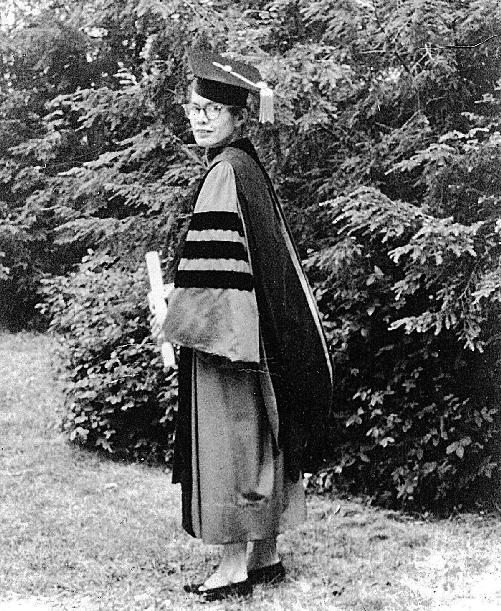

Pauli Murray, age fifty-four, class marshal and first African American to earn a doctorate in the science of law from Yale, New Haven, Connecticut, June 14, 1965. This was her third law degree.

(Photo by Louise E. Jefferson, Patricia Bell-Scott Collection)

61

“I Have Been a Person with an Independent Inquiring Mind”

T

wenty-one years after

Harvard University rejected Pauli Murray’s application to study for a graduate degree in law, she completed her three-volume, 1,308-page dissertation at Yale University.

“

Roots of the Racial Crisis: Prologue to Policy” was a treatise on the historical and legal origins of the American race problem.

Now in possession

of the credential that assured most men of a faculty appointment at a premier law school, Murray faced the irony that only a handful of historically black law schools and not a single predominantly white law school employed a full-time African

American woman professor. Shut out once again from the kind of position she rightfully deserved, she sought alternative means to support herself and use her legal talents.

Murray returned to

New York. Renee and several good friends were there, but her dog,

Smokey, soon died. They had been together for thirteen years. Murray soon adopted

Doc from a local pound. He was a large mutt “

with a clumsy gait” and a black-and-white coat. Murray jokingly referred to Doc on occasion as “Black-and-White-Together-We-Shall-Overcome.”

She signed a contract with the

Methodist Church to write

Human Rights U.S.A.: 1948–1966

, a monograph in which she assessed the history and future of the human rights movement.

She worked as a consultant for the

U.S. Information Service and the U.S. Department of Labor, doing research and writing reports. She served on the American Civil Liberties Union board of directors; the

ACLU’s vice chair,

Dorothy Kenyon, was a liberal activist Joseph

McCarthy had accused of Communist ties.

In 1966, Kenyon and Murray coauthored the union’s brief for

White v. Crook

, successfully challenging an

Alabama statute restricting jury service to males and whites. They also planted the seeds for the

ACLU Women’s Rights Project, which blossomed later under the leadership of future

U.S. Supreme Court justice

Ruth Bader Ginsburg.

Ginsburg would pay homage to Murray and Kenyon by placing their names on the cover of the brief for

Reed v. Reed

, a 1971 precedent-setting case in which the Supreme Court struck down an

Idaho law favoring the appointment of a man because of his sex over his ex-wife to act as the administrator of an estate, in this case their deceased son’s. Murray and Kenyon did not help write the brief; however, Ginsburg, who coauthored the document, felt that their intellectual work had laid the ground for the high court, which held that the

Equal Protection Clause of the

Fourteenth Amendment protected women’s rights.

Like Ginsburg,

Betty Friedan, the author of

The Feminine Mystique

, found inspiration in Murray’s work. Murray came to Friedan’s attention in the fall of 1965 when Freidan read a

New York Times

feature about a conference hosted by the

National Council of Women of the United States at which Murray had said that it might be necessary for women to march on Washington “

to assure equal job opportunities for all.”

Friedan, who was not at the conference, contacted Murray, and they began a series

of conversations with each other and others that resulted in the birth of the National Organization for Women in 1966.

Friedan became the face of NOW and its first president; Murray stayed out of the spotlight, drafting organizational documents imbued with her vision of an

NAACP for women. She would fight for women’s equality for the rest of her life, but her association with NOW’s national board would be short-lived.

Disagreement over the process by which NOW would come to endorse the

Equal Rights Amendment, power struggles within the leadership, insufficient attention to poor and minority women’s concerns, and the lack of appreciation shown her at meetings would lead Murray to resign within a year.

She would publicly endorse the ERA in time, but would remain outside the national leadership structure.

· · ·

AT THE SAME TIME

that Murray was working with Friedan and others to establish NOW, she was also employed as a consultant to the recently established

Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. The EEOC, a federal agency authorized by Title VII of the

Civil Rights Act of 1964, was empowered to investigate and adjudicate claims of discrimination based on race, color, religion, sex, or national origin in the hiring, firing, compensation, and treatment of employees. The commission was composed of five members, who were appointed to five-year terms by the president with the advice and consent of the

Senate. Only three commissioners could be from the same political party. The EEOC general counsel, whose job was to facilitate implementation of the law and the agency’s work, was also appointed by the president with the advice and consent of the Senate.

The agency opened shop on July 2, 1965, at 1800 G Street, NW, two blocks away from the White House. The first commissioners were an interesting group. Democrat

Franklin D. Roosevelt Jr., a former undersecretary of commerce in the Kennedy administration, was named chair. Democrat

Luther Holcomb, a minister and civic leader from Texas, served as vice chair. Democrat

Aileen Clarke Hernandez, a former International Ladies’ Garment Workers’ Union organizer and deputy chief of the California Division of Fair Employment Practices, was the only woman. Republican

Samuel C. Jackson, a lawyer and civil rights leader, was from Kansas. Republican Richard

Graham, a former deputy director of the Peace Corps and a future cofounder of NOW, was from Wisconsin.

Charles T. Duncan, a lawyer and former assistant U.S. attorney for the District of Columbia, was named general counsel.

Aileen Clarke Hernandez, president of NOW and former commissioner of the EEOC, Denver, Colorado, 1971. During her tenure at the EEOC, she and Richard Graham repeatedly challenged their fellow commissioners to address complaints of sex discrimination.

(Getty Images)

Duncan, Jackson, and Hernandez were African American. No

Hispanics were appointed to the EEOC, although President

Johnson’s advisers possibly assumed that Hernandez was Hispanic because of her surname. (She was the daughter of Jamaican immigrants and had married and divorced

Alfonso Hernandez, who was Hispanic.)

The EEOC’s first year was rife with difficulty. The agency was understaffed and besieged by more than eight thousand complaints, one-third of which dealt with sex discrimination. Guidance from Congress, with respect to the agency’s power and limitations, ranged from inadequate to absent; and there was no consensus among the commissioners, the legislators, or the public on the issue of sex discrimination. Years later, Commissioner

Holcomb, whose reluctance to act unnerved Hernandez, would admit that the agency’s “

number one objective” at the beginning “was racial discrimination in the workforce.” Women’s employment concerns were “

second place.”

Frustration with the EEOC’s initial decision (Hernandez and Graham dissented) that permitted employers to continue the practice of segregating

job advertisements into male and female positions led Murray to accuse the agency of violating Title VII of the Civil Rights Act.

When it became apparent that the EEOC’s hiring practices discriminated against

women as much as, if not more than, the employers it was investigating, she drafted and disseminated a chart highlighting the concentration of women and blacks in lower-level, non-policy-making positions.

When EEOC general counsel Charles

Duncan left, in the fall of 1966, to become corporation counsel for the District of Columbia, Murray, as well as her supporters, believed that she was uniquely qualified to fill the vacant post. She had coauthored the groundbreaking and frequently cited law

review essay

“

Jane Crow and the Law:

Sex Discrimination and Title VII” with

Mary O. Eastwood, and she had co-orchestrated the battle to preserve sex as a protected category in the 1964 Civil Rights Act. Murray was elated when her name was sent to the White House. After years of watching her male peers move up the

career ladder in the federal government, she felt that a high-level appointment was within her reach.

In a scenario eerily reminiscent of when she applied for a research position with the

Cornell University

Codification of Laws of

Liberia Project, Murray was asked to document her “

organizational affiliations” from 1930 to 1948 in her application materials. Clearly worried, she asked reviewers to consider several “

factors” as they

examined her record:

1.

That I have been a person with an independent inquiring mind and that my major emphasis has been upon the fulfillment of individual capacities.

2.

That my activist activities and writing during my youth were in furtherance of the sole objective to become an integral part of American life.

3.

That as one whose immediate family has been the victim of violence, I have been particularly

concerned with seeking alternatives to violence in social conflict.

4.

That my employment record reflects the limited job opportunities for Negroes prior to World War II in areas outside of segregated institutions and menial occupations.

5.

That admission to the

New York Bar in June 1948 was evidence of…loyalty to the United States and its institutions since this issue was a key question in the exhaustive questionnaire which all candidates for admission are required to fill out.

Murray’s apprehension was warranted. Despite the testimony of her colleagues, friends, and neighbors to her high character, loyalty, intelligence,

and work ethic, and the fact that no FBI informants close to the

Communist front said they knew her, could confirm that she had ever been a member of the Communist Party USA, or could furnish information about her, the profile presented to the White House was one of suspicion.

Murray was described as a highly educated black woman and a former member of the CPUSA with ties to multiple Communist-front groups. The FBI agents assigned to her investigation, who purportedly accessed

Bellevue

Hospital records and questioned staff members, said doctors had diagnosed her as a schizophrenic who stated upon admission that “

she was a homosexual.” These operatives further noted that she had married Billy Wynn in her twenties, that they had separated shortly after the marriage, and that her marital status was unclear. Her treatment in 1954 for a

thyroid disorder—the symptoms of which may have led doctors to conclude that she was schizophrenic—and the fact that her marriage to Wynn had been annulled in 1949 were absent from the summary report.

The FBI file frightened White House officials. The problem, said one presidential aide, “

was to determine how not to give Murray the job as General Counsel,” as she had been working for “the Government on a consultant basis for some eight months.” Given her first-rate credentials and references, the aide told FBI officials that the best he could do was to “

challenge…her affiliation with Communist Party organizations, the circumstances of her admission and release from Bellevue Hospital, her unconsummated marriage and lack of annulment, and her two arrests and jail sentence.”

When the White House backed away from Murray’s appointment, she lamented in her journal, “

This has been the most crushing blow of my entire career.” At fifty-six, “

no longer young” and yet to achieve a job commensurate with her training and experience, she felt like “

a has-been.” She was “

not part of anyone’s power structure.” She did not have the backing of an established organization. Moreover, the realization that she belonged at the EEOC “

as a Commissioner and not a staff member” compounded her frustration. It had been a mistake, she admitted on the page, to “

try to be what I am unable to be well—a subordinate.” She determined not to remain at the agency in any capacity.