The Fiery Cross (180 page)

Authors: Diana Gabaldon

“That’s right,” I said, nodding as he looked up at me in question. “Exactly right.”

He gave me a small, wry smile in response, then dropped his eyes, studying the charts.

“Can you tell, then?” he asked finally, not looking up. “For sure?”

“No,” I said, and dropped the cloth into the laundry basket with a small sigh. “Or rather—I can’t tell for sure whether Jemmy is yours. I

might

be able to tell for sure if he’s not.”

The flush had faded from his skin.

“How’s that?”

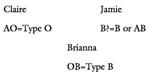

“Bree is type B, but I’m type A. That means she’ll have a gene for B

and

my gene for O, either of which she might have given Jemmy. You could only have given him a gene for type O, because that’s all you have.”

I nodded at a small rack of tubes near the window, the serum in them glowing brownish-gold in the late afternoon sun.

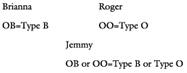

“So. If Bree gave him an O gene, and you—his father—gave him an O gene, he’d show up as type O—his blood won’t have any antibodies, and won’t react with serum from my blood or from Jamie’s or Bree’s. If Bree gave him her B gene, and you gave him an O, he’d show up as type B—his blood would react with my serum, but not Bree’s. In either case, you might be the father—but so might anyone with type-O blood. IF, however—”

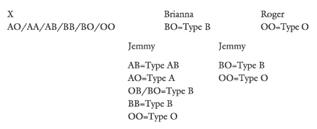

I took a deep breath, and picked up the pencil from the spot where Roger had laid it down. I drew slowly as I talked, illustrating the possibilities.

“But”

—I tapped the pencil on the paper—“if Jemmy were to show as type A or type AB—then his father was not homozygous for type O—homozygous means both genes are the same—and you are.” I wrote in the alternatives, to the left of my previous entry.

I saw Roger’s eyes flick toward that “X,” and wondered what had made me write it that way. It wasn’t as though the contender for Jemmy’s paternity could be just anyone, after all. Still, I could not bring myself to write “Bonnet”—perhaps it was simple superstition; perhaps just a desire to keep the thought of the man at a safe distance.

“Bear in mind,” I said, a little apologetically, “that type O is very common, in the population at large.”

Roger grunted, and sat regarding the chart, eyes hooded in thought.

“So,” he said at last. “If he’s type O or type B, he may be mine, but not for sure. If he’s type A or type AB, he’s not mine—for sure.”

One finger rubbed slowly back and forth over the fresh bandage on his hand.

“It’s a very crude test,” I said, swallowing. “I can’t—I mean, there’s always the possibility of a mistake in the test itself.”

He nodded, not looking up.

“You told Bree this?” he asked softly.

“Of course. She said she doesn’t want to know—but that if you did, I was to make the test.”

I saw him swallow, once, and his hand lifted momentarily to the scar across his throat. His eyes were fixed on the scrubbed planks of the floor, hardly blinking.

I turned away, to give him a moment’s privacy, and bent over the microscope. I would have to make a grid, I thought—a counting grid that I could lay across a slide, to help me estimate the relative density of the

Plasmodium

-infected cells. For the moment, though, a crude eyeball count would have to do.

It occurred to me that now that I had a workable stain, I ought to test the blood of others on the Ridge—those in the household, for starters. Mosquitoes were much rarer in the mountains than near the coast, but there were still plenty, and while Lizzie might be well herself, she was still a sink of potential infection.

“. . . four, five, six . . .” I was counting infected cells under my breath, trying to ignore both Roger on his stool behind me, and the sudden memory that had popped up, unbidden, when I told him Brianna’s blood type.

She had had her tonsils removed at the age of seven. I still recalled the sight of the doctor, frowning at the chart he held—the chart that listed her blood type, and those of both her parents. Frank had been type A, like me. And two type-A parents could not, under any circumstances, produce a type B child.

The doctor had looked up, glancing from me to Frank and back, his face twisted with embarrassment—and his eyes filled with a kind of cold speculation as he looked at me. I might as well have worn a scarlet “A” embroidered on my bosom, I thought—or in this case, a scarlet “B.”

Frank, bless him, had seen the look, and said easily, “My wife was a widow; I adopted Bree as a baby.” The doctor’s face had thawed at once into apologetic reassurance, and Frank had gripped my hand, hard, behind the folds of my skirt. My hand tightened in remembered acknowledgment, squeezing back—and the slide tilted suddenly, leaving me staring into blank and blurry glass.

There was a sound behind me, as Roger stood up. I turned round, and he smiled at me, eyes dark and soft as moss.

“The blood doesn’t matter,” he said quietly. “He’s my son.”

“Yes,” I said, and my own throat felt tight. “I know.”

A loud crack broke the momentary silence, and I looked down, startled. A puff of turkey-feathers drifted past my foot, and Adso, discovered in the act, rushed out of the surgery, the huge fan of a severed wing-joint clutched in his mouth.

“You

bloody

cat!” I said.

CLEVER LAD

A

COLD WIND BLEW from the east tonight; Roger could hear the steady whine of it past the mud-chinked wall near his head, and the lash and creak of the wind-tossed trees beyond the house. A sudden gust struck the oiled hide tacked over the window; it bellied in with a

crack!

and popped loose at one side, the whooshing draft sending papers scudding off the table and bending the candle flame sideways at an alarming angle.

Roger moved the candle hastily out of harm’s way, and pressed the hide flat with the palm of his hand, glancing over his shoulder to see if his wife and son had been awakened by the noise. A kitchen-rag stirred on its nail by the hearth, and the skin of his bodhran thrummed faintly as the draft passed by. A sudden tongue of fire sprang up from the banked hearth, and he saw Brianna stir as the cold air brushed her cheek.

She merely snuggled deeper into the quilts, though, a few loose red hairs glimmering as they lifted in the draft. The trundle where Jemmy now slept was sheltered by the big bed; there was no sound from that corner of the room.

Roger let out the breath he had been holding, and rummaged briefly in the horn dish that held bits of useful rubbish, coming up with a spare tack. He hammered it home with the heel of his hand, muffling the draft to a small, cold seep, then bent to retrieve his fallen papers.

“O will ye let Telfer’s kye gae back?

Or will ye do aught for regard o’ me?”

He repeated the words in his mind as he wiped the half-dried ink from his quill, hearing the words in Kimmie Clellan’s cracked old voice.

It was a song called “Jamie Telfer of the Fair Dodhead”—one of the ancient reiving ballads that went on for dozens of verses, and had dozens of regional variations, all involving the attempts of Telfer, a Borderer, to revenge an attack upon his home by calling upon the help of friends and kin. Roger knew three of the variations, but Clellan had had another—with a completely new subplot involving Telfer’s cousin Willie.

“Or by the faith of my body, quo’ Willie Scott.

I’se ware my dame’s calfskin on thee!”

Kimmie sang to pass the time of an evening by himself, he had told Roger, or to entertain the hosts whose fire he shared. He remembered all the songs of his Scottish youth, and was pleased to sing them as many times as anyone cared to listen, so long as his throat was kept wet enough to float a tune.

The rest of the company at the big house had enjoyed two or three renditions of Clellan’s repertoire, began to yawn and blink through the fourth, and finally had mumbled excuses and staggered glazen-eyed off to bed—

en masse

—leaving Roger to ply the old man with more whisky and urge him to another repetition, until the words were safely committed to memory.

Memory was a chancy thing, though, subject to random losses and unconscious conjectures that took the place of fact. Much safer to commit important things to paper.

“I winna let the kye gae back,

Neither for thy love, nor yet thy fear . . .”

The quill scratched gently, capturing the words one by one, pinned like fireflies to the page. It was very late, and Roger’s muscles were cramped with chill and long sitting, but he was determined to get all the new verses down, while they were fresh in his mind. Clellan might go off in the morning to be eaten by a bear or killed by falling rocks, but Telfer’s cousin Willie would live on.

“But I will drive Jamie Telfer’s kye,

In spite of every Scot that’s . . .”

The candle made a brief sputtering noise as the flame struck a fault in the wick. The light that fell across the paper shook and wavered, and the letters faded abruptly into shadow as the candle flame shrank from a finger of light to a glowing blue dwarf, like the sudden death of a miniature sun.

Roger dropped his quill, and seized the pottery candlestick with a muffled curse. He blew on the wick, puffing gently, in hopes of reviving the flame.

“But Willie was stricken owre the head,”

he murmured to himself, repeating the words between puffs, to keep them fresh.

“But Willie was stricken owre the head/And through the knapscap the sword has gane/And Harden grat for very rage/When Willie on the grund lay slain . . . When Willie on the grund lay slain . . .”

A ragged corona of orange rose briefly, feeding on his breath, but then dwindled steadily away despite continued puffing, winking out into a dot of incandescent red that glowed mockingly for a second or two before disappearing altogether, leaving no more than a wisp of white smoke in the half-dark room, and the scent of hot beeswax in his nose.

He repeated the curse, somewhat louder. Brianna stirred in the bed, and he heard the corn shucks squeak as she lifted her head with a noise of groggy inquiry.